24 24 For project outlines of such a concept of the history of theory, see Marcel Lepper, ‘“Ce qui restera […], c’est un style”: Eine institutionengeschichtliche Projektskizze (1960–1989)’, in Jenseits des Poststrukturalismus? Eine Sondierung, ed. Marcel Lepper, Steffen Siegel and Sophie Wennerscheid, Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2005, 51–76; Warren Breckman, ‘Times of Theory: On Writing the History of French Theory’, in Journal of the History of Ideas, 71:3 (2010), 339–61.

25 25 Michel Foucault, ‘I “reportages” di idee’, in Corriere della sera, 12 November 1978, 1. Foucault’s project largely remained just that. The only ‘reportage’ of ideas he wrote himself is his controversial series on the Iranian revolution of 1979.

1965 THE HOUR OF THEORY

1 FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF ADORNO

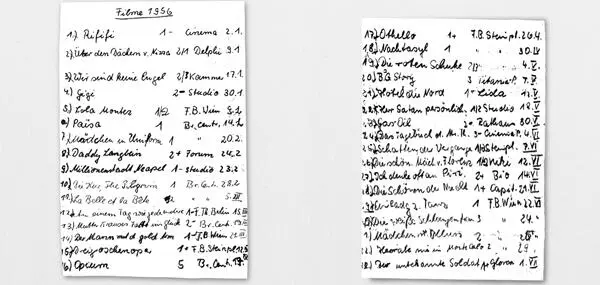

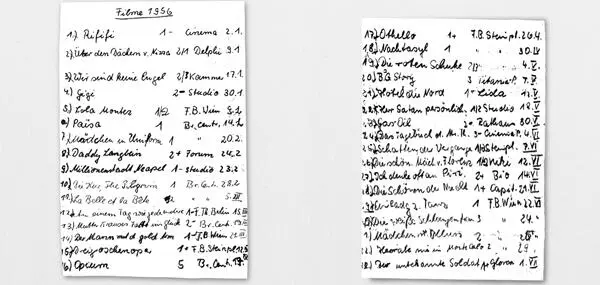

3 Peter Gente goes to the cinema, 1956. 1

While Radio Free Berlin was broadcasting Nikita Khrushchev’s secret speech, Peter Gente went to the cinema. As the radio waves rose into the evening sky, informing listeners on both sides of the divided city about the crimes of Stalinism, the curtain opened on Beauties of the Night , a comedy by René Clair about a young composer escaping into dreams of success and beautiful women, losing his connection to reality – until the end of the film, when he comes to his senses just in time to face real life. 2Gente was ecstatic, and gave the film a grade of ‘1+’ in his culture diary. He went to the cinema often in those days, and also visited Berlin’s theatres, concert halls and cultural centres. He had discovered his passion for culture after moving with his parents to the metropolis from the Soviet-occupied provinces. He began reading novels with the zeal of a late bloomer, and invested what money he earned at his summer jobs in admission tickets. 3Herbert von Karajan was the director of the Berlin Philharmonic. The Berliner Ensemble was an unbeatably affordable theatre at the unofficial exchange rate between Western and Eastern marks, and Brecht himself still watched from his box. And the cinemas showed films from France and Italy that broke with the aesthetics of the pre-war generation. 4On the eve of the Nouvelle Vague, Gente surrendered to the spells of Fellini, Hitchcock, Orson Welles and Jean Cocteau. ‘Read bourgeois novels; consumed culture generally’ was his summary of this period in a later self-criticism before his socialist comrades. 5

Karl Marx once commented that the Germans are philosophically contemporary with the present day, but not historically. 6In Gente’s life too, major political events were only background noise. Although he lived at the epicentre of the Cold War, he hardly seems to have noticed Khrushchev’s speech, which heralded a thaw in the East and a disenchantment among the intellectual left in the West. 7But perhaps Berlin was precisely the wrong place to develop a stable sense of reality. There were too many realities coexisting here: the ruins of the World War, and the monuments of the post-war economic miracle; the Kurfürstendamm in the West with its cafés full of buttercream cakes, and the Stalin-Allee in the East with its socialist gingerbread housing blocks. To Maurice Blanchot, whom Gente later counted among his favourite authors, Berlin ‘was not … just one city, or two cities’, but ‘the place in which the question of a unity which is both necessary and impossible confronts every individual who resides there, and who, in residing there, experiences not only a place of residence but also the absence of a place of residence’. 8

This is what it sounds like when a geopolitical situation invites metaphysical speculation. But, in 1956, Gente did not yet see the world in the light of theory. In a round script that betrays his youth, he kept a record of his evenings at the cinema and the theatre, and the minimalistic prose of his lists seems to quiver with pent-up desire. Gente was burning to find a place for himself in the world of the arts, 9and his readings soon influenced him to limit his search to the canon of high culture. In the year of the thaw, however, his taste had not yet matured. His diary mixes musicals with auteur cinema, Puccini with Hollywood and Brecht. It was up to him to discover a common denominator. In the meantime, he awarded the performances grades from 1 to 5 – the scale used by German secondary schools, including the one he had recently left. The numbers were a relatively modest instrument of cultural criticism, taking no notice of highbrow or lowbrow categories. At the same time, Susan Sontag, negligibly older, was already jotting savvy mini-reviews in her diary as she made her own cultural rounds in Chicago. 10Gente’s marks went no higher than the superlative ‘1++’ for Giorgio Strehler’s adaptation of Harlequin, Servant of Two Masters , performed by the visiting Piccolo Teatro of Milan, and no lower than the moderate ‘3’ for Puccini’s La Bohème . He was an easy grader who repeatedly had to expand his scale upwards because, worshipper of culture, he had started out awarding too many 1s.

Reflections from Damaged Life

The following year, in 1957, Gente had an awakening. It occurred, however, not in the cultural sphere where he was seeking his future, but at the base, in wage labour. The scene is symptomatic of the young West Germany, which was already approaching full employment in the second half of the 1950s. On the assembly line of the Siemens factory in Spandau, where Gente worked to support himself while studying law – in accordance with his father’s wishes – he listened to two of his fellow students talking about a certain Adorno, whom they seemed for some reason to consider absolutely essential. Exactly what it was that captured his attention, he couldn’t remember later on. But the impression it made was certainly deep. ‘Adorno challenged earlier life’, Gente’s later self-criticism states tersely. 11He got a copy of Adorno’s best-known book, Minima Moralia , and couldn’t put it down, although he understood hardly any of its impenetrable aphorisms. 12Yet the author, claiming that only thoughts ‘which do not understand themselves’ can be true, apparently saw the hermetic tone as part of his message. 13The difficult language, yielding its meaning only to patient reflection, contributed to the influence of a book which made those Gente had read before it seem irrelevant. 14

In 1957, Adorno’s ‘reflections from damaged life’, as Minima Moralia ’s subtitle calls them, were still an insider tip. Six years after its publication, there was little to indicate that the book would be a philosophical hit, selling over 120,000 copies to date. In the middle of the post-war boom, between Opel Rekords and ice cream parlours, Gente was unsettled by it – by the way of thinking of a little-known Frankfurt philosophy lecturer who saw only disaster wherever he looked. ‘Life does not live’, reads the epigram, like a warning, on the first page; the pages that follow contain variations on that paradox. Condensing his experience of American exile into miniatures, Adorno exposes modern life as a state of deception. What seems to be alive and authentic is in reality long dead; the apparent aspiration to progress is caused by a ghostly compulsion to keep moving. 15It is a post-cataclysmic world we are living in. ‘The disaster does not take the form of a radical elimination of what existed previously’, a key passage reads – ‘rather the things that history has condemned are dragged along dead, neutralized and impotent as ignominious ballast’. Hence the macabre atmosphere of Minima Moralia : its pages are populated by the undead. Among the figures whose eerie ‘post-existence’ Adorno exposes are the achievements of the preceding bourgeois era – such as liberalism, socialism and the hospitality industry, which reached a state of rigor mortis with the advent of room service. Adorno discovers the ghastliest signs of decay in the tiniest details of day-to-day life – hence his now famous observations that the inhabitants of the Enlightened hemisphere no longer know how to give gifts, to be at home in their homes, or to close a door. ‘The world is systematized horror’ is his judgement of the present. That condemnation had the sinister weight, two decades before Apocalypse Now , of Coppola’s Colonel Kurtz watching a snail crawl along a razor’s edge. Meanwhile, German radios played the sentimental songs of the Austrian rover Freddy Quinn. 16

Читать дальше