The oldest documents dated back to the late 1950s, when Gente discovered the books of Adorno. That discovery changed everything. For five years, the young man ran around West Berlin with Minima Moralia in his hand, before he finally got in touch with the author. By then, Gente was in the middle of the New Left’s theoretical discussions, combing libraries and archives in search of the buried truth of the labour movement. He was everywhere, cheering Herbert Marcuse in the great hall of Freie Universität, demonstrating with Andreas Baader in Kurfürstendamm, running into Daniel Cohn-Bendit in Paris a few weeks before May of ’68. Later, he had discussions with Toni Negri, sat in jail with Foucault, put up Paul Virilio in his shared flat in Berlin. There was never any question that he belonged to the movement’s avant-garde – yet he kept himself in the background. It was a long time before he found his role; he didn’t care to play the part of an activist, nor that of an author. ‘Tried to intervene, but wasn’t able to do so’ was his summary of the year 1968. 9

From the beginning, Gente had been, above all, a reader. The scholar Helmut Lethen, who had known him since the mid-1960s, called him the ‘encyclopaedist of rebellion’. 10He knew every ramification of the debates of the interwar period; he knew how to lay hands on even the most obscure periodicals; his comrades’ key readings were selected on his recommendation. Compared with Baader – whom he supplied with books in Stammheim Prison – Gente embodied the opposite end of the movement: the man I met in 2010, and questioned about his past, interacted with the world through text. 11In preparation for our conversations, he would arrange books, letters and newspaper articles, and he picked them up in turn as he talked, to underscore one point or another. In the echo chamber of the theories that he mastered as no other, he had found his vital element. Professor Jacob Taubes, a gifted reader in his own right who counted Gente among his disciples, attested in 1974 to Gente’s talent for ‘dealing intensively with unwieldy texts’. 12One of the peculiarities of the theory-obsessed ’68 generation is that hardly any theoreticians originated in their ranks. ‘As they silenced their fathers, they allowed their grandfathers to be heard again – preferably those who had been exiled’, 13the cultural journalist Henning Ritter wrote. Was he thinking of Peter Gente, who had served alongside him as a student assistant to Taubes in the 1960s? From that perspective, Gente was the ideal New Leftist: a partisan of the class struggle mining the archives. 14

Gente travelled to Paris and brought back texts by Roland Barthes and Lucien Goldmann, authors no one knew in Berlin. Towards the end of the sixties, when the leftist book market began booming, he picked up odd editorial jobs. But he didn’t find his life’s theme until, in his mid-thirties, he decided to start his own business: in 1970, he and some friends and comrades founded the publishing company Merve Verlag. Initially, they called themselves a socialist collective. As their political beliefs evolved, however, the organization of their work changed as well. For two decades, Merve shaped the theory scene of West Berlin and West Germany. From the student movement’s latecomers to the avant-garde of the art world, everyone got their share of dangerous thinking: Italian Marxism, French post-structuralism, a dash of Carl Schmitt, topped off with Luhmann’s sober systems theory.

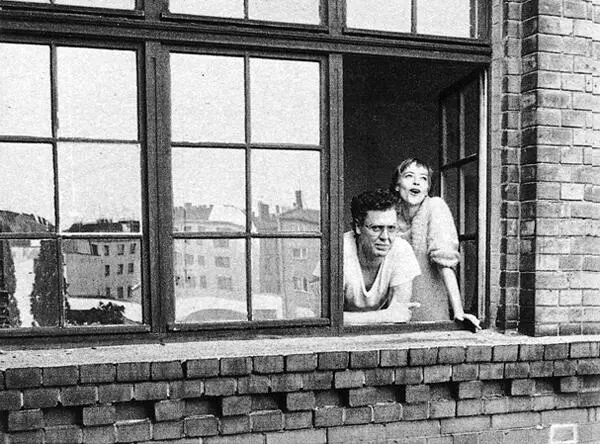

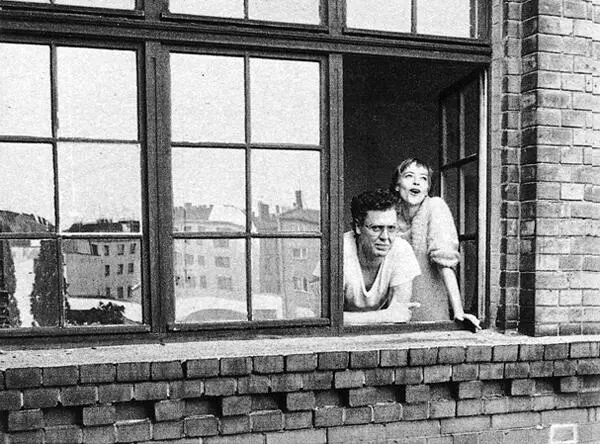

2 Heidi Paris and Peter Gente, West Berlin, around 1980.

But Merve probably never would have been anything more than just a minuscule leftist publisher whose products occasionally turn up in Red second-hand bookshops if Gente hadn’t met Heidi Paris. In the masculine world of theory, where women were all too often reduced to the roles of mothers or muses, she was a pioneer. 15She led the group’s publishing policy in new directions, contributing to the dissolution of the collective. From 1975 on, she was Gente’s partner both in work and in a personal relationship. The couple composed Merve’s legendary long-sellers, established authors such as Deleuze and Baudrillard in Germany, and steered their publishing house into the art world, where it has its habitat today. They produced books that didn’t want to be read at university; they transformed readers into fans, and authors into philosophical fashion icons. They worked on film projects with Blixa Bargeld and Heiner Müller; they did the rounds of the Schöneberg clubs with Martin Kippenberger. 16As well-entrenched members of the theory crowd, they coexisted with a like-minded milieu whose centre of gravity was the university, but whose orbit passed through Berlin’s smart night spots. Or vice versa. In the 1980s, the Merve paperbacks were required reading in this milieu.

‘We are almost never in Paris and are happy living in Berlin’, Heidi Paris and Peter Gente wrote in 1981 to the New York professor Sylvère Lotringer. 17West Berlin was an ideal location for the publishers. Speculative thinking flourished in the city’s exceptional political conditions. The Merve culture grew lavishly between the bars and discos of Schöneberg and the lecture halls of Dahlem. Berlin in the sixties had been a bastion of the New Left; in the seventies, it became a biotope of the counter-culture. And in the eighties, as the Cold War ideologues faded to spectres, postmodernism dawned. Hegel himself had held the Prussian capital to be the home of the World Spirit; his critical heirs thought it nothing less – although the existence of the ‘enclave on the front lines’, as Heidi Paris once called her city, actually seemed to contradict Hegel’s theory. 18

The history of the publishing couple of Gente and Paris is inseparably connected with West Berlin, yet it is more than an intellectual milieu study of the city. People in Germany tend to equate the heyday of theory with what was known as ‘Suhrkamp culture’: the phrase was coined in 1973 by the English critic George Steiner, referring to the catalogue of the Frankfurt publishing house Suhrkamp as the canon of West Germany. 19And, in fact, Suhrkamp played a crucial part in shaping and propagating the genre, as we shall see. Their policy of producing theory in paperback was one thing that made a project such as Merve possible in the first place. But because the Berlin publishers never blossomed out into a company with employees, proper bookkeeping and the imperative of profitability, the files I discovered in Karlsruhe afford a different perspective: they recount the long summer of theory from a user’s point of view. All their lives, the Merve publishers and their friends identified themselves as avid readers. Accordingly, Merve was not just a publisher, but a reading group, a fan club – a reception context.

That fact is an invaluable advantage for my project of writing the history of a genre: to understand the success of theory since the sixties, examining how it was read and used is at least as important as its content 20– which has long since been studied in any case – as the recently published memoirs of some former theory readers have pointed out. 21Perhaps certain texts had a power of suggestion that was even greater than their systematic argument. This preliminary intuition, and the methodological choice which follows from it, are not aimed at adding yet another interpretation to the history of twentieth-century philosophy. 22This book recounts the formative experiences of Peter Gente, the odyssey of the Merve collective, and the discoveries of Gente and Paris. It follows the course of their readings, their discussions and their favourite books – but it does not seek to penetrate the grey contents of those texts. The history of science has long had its eye on ‘theoretical practice’, to use the Merve author Louis Althusser’s term for the business of thinking. Following him and others, that history has learned to pay attention to the media, institutions and practices of knowledge. 23Why should this approach not prove fruitful for the theory landscape of the sixties and seventies, the environment in which it was originally formulated? 24In 1978, Michel Foucault developed the concept of philosophical reporting – ‘le reportage d’idées’, a form devoted to the real history of thought. ‘The world of today is crawling with ideas’, he wrote, ‘that are born, move around, disappear or reappear, shaking up people and things.’ Hence, there is always a need ‘to connect the analysis of what we think with the analysis of what happens’. 25This book’s purpose is precisely that.

Читать дальше