Planet Formation and Panspermia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Planet Formation and Panspermia» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Planet Formation and Panspermia

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Planet Formation and Panspermia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Planet Formation and Panspermia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Audience

Planet Formation and Panspermia — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Planet Formation and Panspermia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Arguably, this kind of directed panspermia—an unintentional consequence of space activities of technological civilization—was not what Crick and Orgel had in mind. Intentional seeding of other habitats is certainly more interesting, but also more speculative, for obvious reasons. There is a parallel here with the transmission of non-native plants and animals between continents on Earth by humans. Obviously, humans transmitted useful crops like potato or maize from one continent to the rest of the world; equally obviously, transmission of various pathogens or the ten-lined potato beetle was unintentional and brought immense harm to humanity. Let us suppose that an advanced technological civilization will be capable of clearly separate the intentional from unintentional and to regulate the unintentional with 100% efficiency. Do such societies engage in intentional seeding of other worlds?

Again, we should try to take a look into the future of humanity first. There have been speculations and suggestions from time to time that humans could and indeed should seed other planets with the terrestrial kind of life. The reasoning is often based on a form of biocentric ethics: since planet with life is inherently more valuable than a dead planet, we ought to intervene when we encounter a dead—but potentially habitable—planet. 8 The strongest contemporary proponent of directed panspermia and our ethical obligations of seeding the universe with life has been the American physical chemist Michael N. Mautner. In a series of papers and books, he has promoted the view that we have a duty to spread life throughout a presumably (mostly) dead universe [3.46–3.48]. Even more, he founded The Panspermia Society in 1995, with the explicit goal of bringing this moral imperative to practical fruition. Since the astrobiological revolution started about the same time, all this has resulted in much more vigorous discussions of the relevant technical and bioethical topics.

We cannot enter here into the latter aspect of the problem: as much as Mautner and others have argued that it is in fact our moral duty to seed other worlds [3.48], there are many astrobiologists and bioethicists who argue to the contrary (e.g., [3.49, 3.52]). This bioethical dilemma will remain with us for quite some time, one may safely presume. There is, however, one angle which has not been sufficiently discussed so far, namely, that the outcome of the debate has a political, as well as ethical, aspects. Even today, it seems plausible that private actors—for instance, companies such as SpaceX— can, if they so desire, launch proverbial soda-cans full of bacteria directed at Mars, Europa, or even some of the recently discovered extrasolar planets. Barring global nuclear war, or some other existential cataclysm, it is virtually certain that the launch mechanisms will become cheaper and more widely accessible in the future. We are not talking about some astronomically distant future, but the future unfolding on the timescales of years, decades, or at most centuries from now. There has been some revival of interest in all forms of panspermia ideas recently (e.g., [3.7, 3.32, 3.57]), which would hopefully give us better insight into the constrains and requirement for the long-term viability of any simple life forms in a variety of cosmic environments. Also, it could be easily shown that directed panspermia can be easily incorporated into a general category of numerical simulations in astrobiology [3.21].

However, if we wish to avoid the pitfall of chronocentrism, we have to take into account the “unthinkable”, namely, to speculate about what the future of human civilization or the past/present of advanced extraterrestrial civilizations may contain. This is not a luxury and it is not optional. The temporal scales of astrophysics and evolution are so much greater than those of human culture, so there are many temporal viewpoints of which we have no historical experience, even if we neglect all other parameter differences. While we cannot be certain that the same is valid for observers in other cosmic civilizations, it is reasonable to assume that a similar relationship between astrophysical and cultural timescales exists in at least that segment of civilizations emerging in physical conditions similar to those on Earth. 9

Capabilities of advanced technological civilizations are, of course, unknown at present. However, it is exactly the reason why we are justified in using a general heuristics like the extended continuity thesis in thinking about them. Together with other general principles guiding our thinking (e.g., scientific realism, naturalism, and Copernicanism), we are free to modify or abandon them as the empirical data comes in— whenever that occurs. To insist that because we do not possess such data at present, in an early epoch of both our own and cosmic evolution, we should censor our thinking, is to succumb to chronocentrism of the worst sort. 10

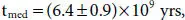

The other key input is the rate of habitat formation in the course of the Galactic history. The pioneer study of Charles Lineweaver [3.42]—and the subsequent improvements by [3.9, 3.43, 3.64]—indicates that the median age of Earth-like planets in the Galaxy is

which is significantly greater than the Earth/Solar System age. Since roughly that epoch, the rate of formation of terrestrial planets in the Milky Way has steadily decreased. While this can be used to strengthen Fermi’s Paradox (as argued at length in [3.14]), there are other interesting speculative applications of the Lineweaver timescale.

Notably, this timescale justifies our previous conclusion that we are living in an early epoch of evolution of our own brand of intelligent observers. The fact that we have discovered these timescales now and have our, even very crude and simplistic, models of the relevant processes implies that older and more advanced civilizations have much better and precise insight into the same. Thus, a Kardashev’s Type 2.x civilization is likely to be able not only to survey all sites for abiogenesis in the Galaxy but is likely to be able to predict the emergence of future habitable sites. Moreover, an implication of the research of Lineweaver and others is that, as far as terrestrial planet formation is concerned, the Milky Way is past its prime: the rate of such habitat formation already decreased and will continue to decrease in the future. A clear implication is that the rate of local occurrences of abiogenesis is decreasing and will continue to decrease.

This happens due to the processes of chemical evolution and star formation which we have studied. However, it also happens due to another, intuitively obvious, but so far not quantitatively studied process: the emergence of life and intelligence itself at individual sites in the Galaxy implies that the available number of sites for future emergencies of this kind is decreasing. In other words, if life emerges somewhere and persists, there are less “slots” left for such future emergencies in the Galaxy as a whole. This effect may or may not be very small so far—its magnitude depends on the intrinsic probability of local abiogenesis (averaged appropriately). While the continuity thesis tells us that this intrinsic probability should not be 10 −100, we cannot say whether it is 10 −6, 10 −3, 0.1, or 0.9, which the magnitude of the “filling the slots” effect, as manifested so far, hinges upon. However, what we may be rather certain is that in the future the effect will gain in importance. Especially as the number of habitable “slots” intrinsically falls off.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Planet Formation and Panspermia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Planet Formation and Panspermia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Planet Formation and Panspermia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.