In spite of Seedhouse’s (1995) concern about the use of a valid, reliable, and maybe unified methodology to analyze interaction in the second or foreign language classroom, discourse analysis has also been applied to explain other communicational realities embraced by interaction. Nunn (2001) uses a specific discourse analysis approach “to redefine the relationship between ritual and negotiation in ‘lock-step’ teaching in the light of research findings and recent re-evaluation of the notion of ritual in educational settings” (Nunn, 2001, p. 1). A lock-step teaching context is, for example, a rigidly structured lesson that does not allow unexpected changes in its own interactional processes due to the roles traditionally assigned to both teachers and students. Teachers are the ones who deliver knowledge and students are recipients of such knowledge. After analyzing several pieces of language excerpts from language classrooms, the researcher considers that discourse analysis cannot be relegated to a static model. This will shorten the view for teachers concerning finding out about more possibilities of using language in a creative way involving pedagogical significance and interest. This means that discourse analysis has an impact on curriculum development, methodology and teaching practices. If a model provided by discourse analysis dares to imply that the best way to teach is to have teacher-fronted classroom instruction, then teachers will be trained to perform in such a way. The author goes on to say that reducing interaction and teachers’ speeches to “structure misrepresents teacher-fronted classroom discourse as being more rigid and meaningless than it is. The characterization of rituals and exchanges as repertoires of limited choices is intended to redress the balance” (Nunn, 2001, p. 7). Nunn’s (2001) contribution should be added to the enormous quantity of work dealing with the study of classroom language (upon which this paper does not report). In writing this paper the author sought to outline how classroom language has been significantly researched by discourse analysis.

As a partial conclusion, it could be stated that discourse analysis transforms, apparently, in the same direction as conversation analysis. Both approaches to discourse manifestation refer to research dating from the early 1940’s. Discourse analysis has particularly focused on studying the language used in the classrooms, but due to the changeable nature of a classroom, discourse analysis has to reflexively approach its object of study and examine the best procedure with which to conduct analysis. Otherwise, discourse analysis will be unable to find a clear definition of its own limits and scope.

So far this chapter has mentioned several different approaches to discourse analysis; among them, it is possible to enumerate linguistics, socio-linguistics, speech acts, systemic functional linguistics and post-structuralist feminism. In general, discourse analysis applied to second or foreign language classrooms has been derived from first language classroom findings. The main concern discourse analysts have had is that of finding a structure that supports all kinds of possible interactions in the language classroom. A variety of meta-language has been created to explain how interactions occur within a language classroom; concepts like move, cycle, and genre are intended to theoretically support patterns of classroom interaction. However, this goal has been considered difficult to attain because what is necessary, according to some discourse analysts, is to remove the tension between what is linguistic and what is pedagogic. The ultimate goal in the language classroom arena for discourse analysts interested in foreign language settings could be to give account of how linguistic issues shape pedagogical events and vice versa in a systematic way. The explanation of how language is learnt through language would, in the future, advise all those who are involved in the processes of teaching and learning a second or foreign language. Some discourse analysts of foreign language classrooms recommend that one start by constructing a corpus. This should be representative enough to undertake systematic studies of interactions in foreign language classrooms according to generational groups (for example). Moreover, the assessment of a methodology within a multiple or interdisciplinary but coherent and limited approach to classroom discourse analysis is also needed and cannot be the focus of the chapter reconstructing the history of classroom discourse analysis as a field of interest.

The main purpose of this chapter was to review how classroom language has been studied especially in the context of the teaching of foreign and/or second languages. In order to achieve this goal, I started presenting how classroom language is different from a typical conversation. That difference was argued using two criteria, which I called symmetry and level of formality. However, symmetry and level of formality do not fully differentiate classroom language and conversations. This happens because both classroom language and conversations are contingent and to a very large extent depend on context; it is this last feature that makes them differ. I also outlined two additional concepts: text and discourse. I will maintain for the purposes of my own research that classroom discourse is text-context situated and will not argue about differences between text linguistics and semantic linguistics, which at the end have the same units of analysis but are investigated from a rather different, abstract point of view.

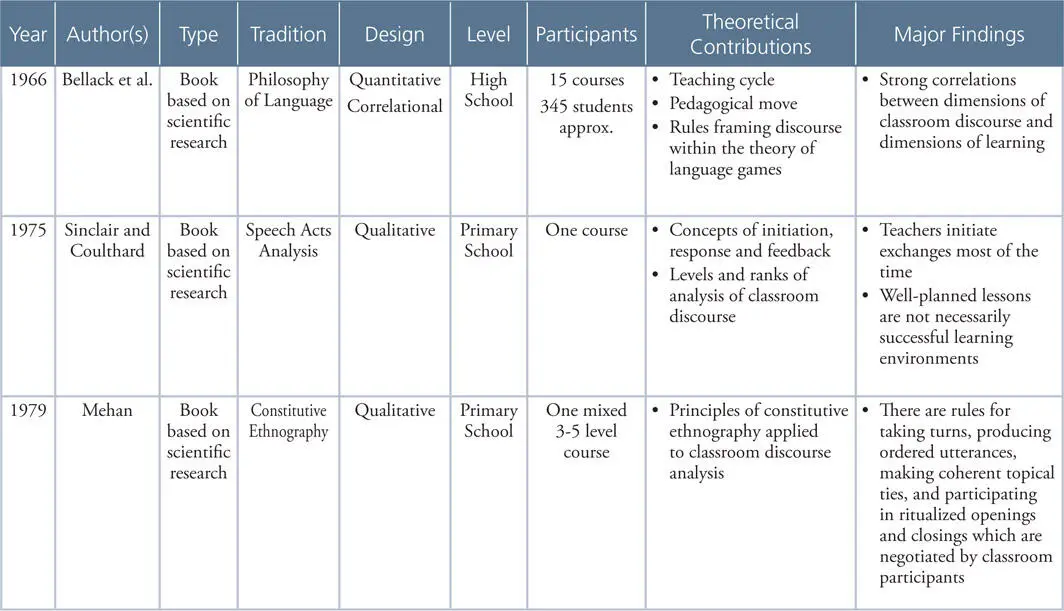

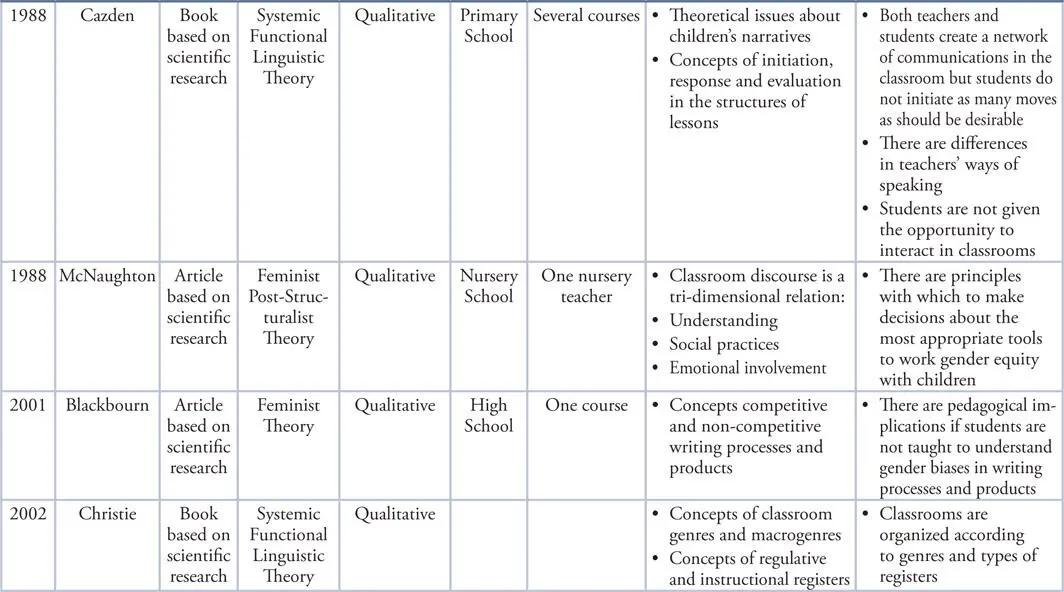

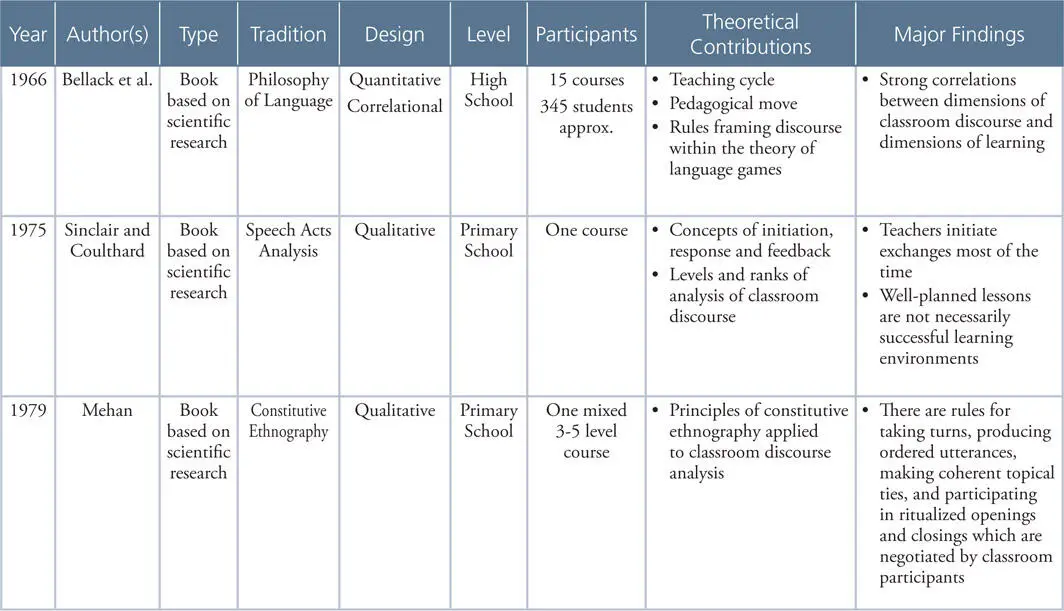

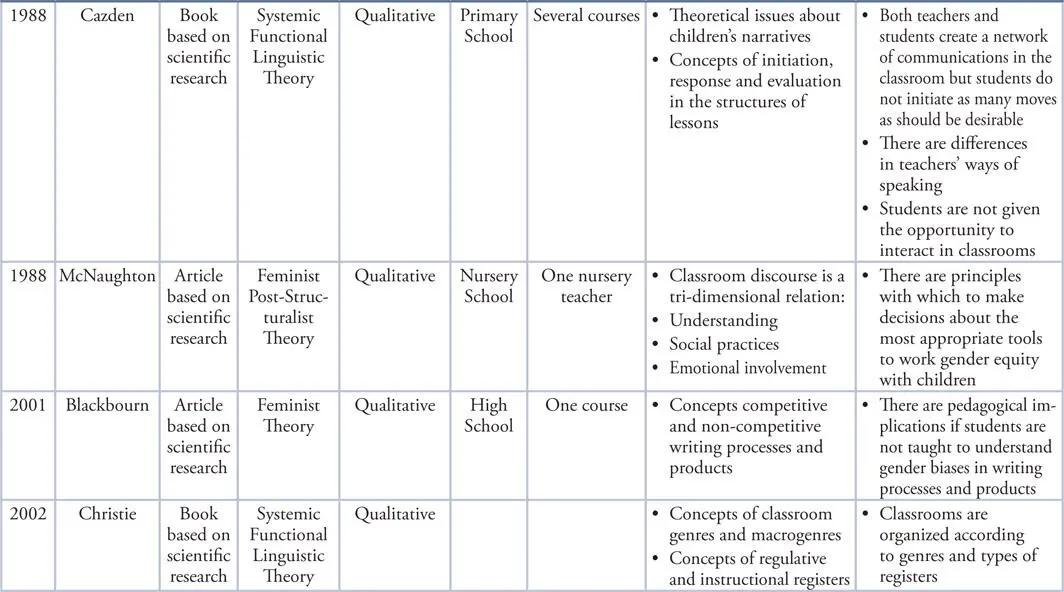

Classroom language has been researched in the few past decades through different approaches. Table 3 summarizes my first attempt to map out a very succinct account of classroom discourse analysis. Table 3 has been organized chronologically, so the first column refers to the year the research or article was published. The name of the main researcher will be found in the second column. Column three has the type of article or book. There are different kinds of articles in this brief presentation of research about classroom discourse analysis. Some of them are either books or articles based on scientific research. By scientific research I mean that kind of investigation described in a report where it is easy to distinguish a research question and the attempt to answer it by following a rigorous process of validation or demonstration. Other articles are revision or reflection articles. The fourth column displays what has been called the tradition. Tradition in this context refers mainly to the discipline of origin from which the study derives; such discipline scaffolds the theoretical framework supporting the study and the approach to the analysis of results. The fifth column describes whether or not the study approaches the research question from a quantitative or a qualitative point of view or even from a complementary analysis between these two options. This column will also point out whether or not the study simply presents a theoretical explanation of specific phenomena. Columns number 6 and 7, when applicable, present the research participants and the level on which the research was conducted. Finally, the two last columns highlight the major theoretical contributions and summarize the main findings for each study. Some of the works outlined in this review do not clearly present theoretical contributions or conceptual variations in the sense that there is no theory construction; rather, these are used to present what has been already established in the discipline of origin.

Table 3. Brief Relation of Classroom Discourse Models in General Educational Contexts.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Читать дальше