| Teacher |

Can you tell me why you eat all that food? Yes. |

Move 1 |

|

| Pupil |

To keep you strong. |

Move 2 |

|

| Teacher |

To keep you strong. Yes. |

|

Exchange 1 |

|

To keep you strong. |

Move 3 |

|

Why do you want to be strong? |

Move 4 |

Move 1 corresponds to a typical teacher initiation, a question in the example above, which is clearly limited by a type of boundary marked by the word ‘Yes ’; in oral speech, those boundaries could also be identified by rising or falling intonations. The initiation is followed by Move 2, which is a response provided by the student and corresponds to an archetypal answer that expresses purpose by using an infinitive construction. Finally, there is an immediate teachers’ reaction or feedback, represented by Move 3, which in the example corresponds to a variety of paraphrasing. The teacher repeats what the student has said, places a boundary again, and reiterates ‘to keep you strong’ to introduce Move 4 which is the initiation of an additional exchange. The example was taken from Sinclair and Coulthard (1975, p. 21) but the analysis is mine. It differs somewhat from the analysis provided by the authors for whom all the utterances in the example constitute a single exchange and to whom there appear to be only three moves. If I looked at the example again, I would have split the feedback move into two separate moves since the teacher is clearly marking a boundary between them. Yet, such minutia, 35 years later, does not affect the authors’ initial proposal and it would imply deeply re-examining Sinclair’s and Coulthard’s classification of interrogatives by situations and doing so is not the purpose of this chapter.

Additionally, moves are made of smaller units called acts; different exchanges construct a transaction and a group of transactions are part of a lesson. To sum up, acts, moves, exchanges, transactions and lessons are ranks that belong to the discourse level and each rank has its own structure realized by units at the rank below. Sinclair and Coulthard created their model while aware of the difference between what could be considered pedagogical and what could be called linguistic in a classroom situation. The former is a major unit like a course while the latter is a portion of speech or linguistic interaction with a specific purpose within a lesson, which is a discourse unit. Sinclair and Coulthard (1975, p. 24) illustrate those levels and ranks as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Levels and ranks of Analysis of Classroom Discourse (Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975).

| Non-Linguistic Organization |

DISCOURSE |

Grammar |

| course |

|

|

| period |

LESSON |

|

| topic |

TRANSACTION |

|

|

EXCHANGE |

|

|

MOVE |

sentence |

|

ACT |

clause |

|

|

group |

|

|

word |

|

|

morpheme |

It is notable how Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) understand the level of discourse as a linking category between what is pedagogic (course, period, topic) and what is fundamentally grammatical (sentence, clause, group, word, morpheme).

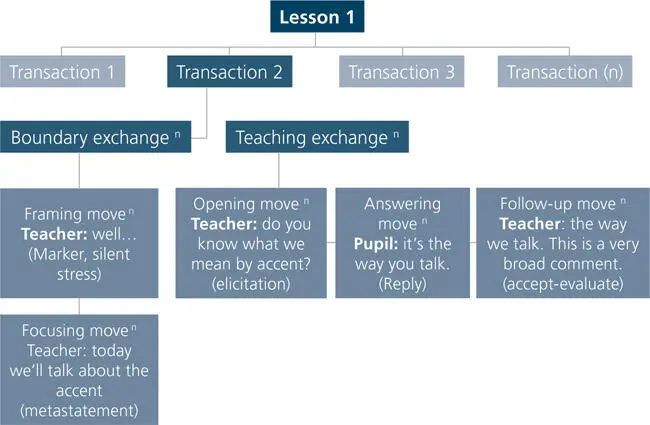

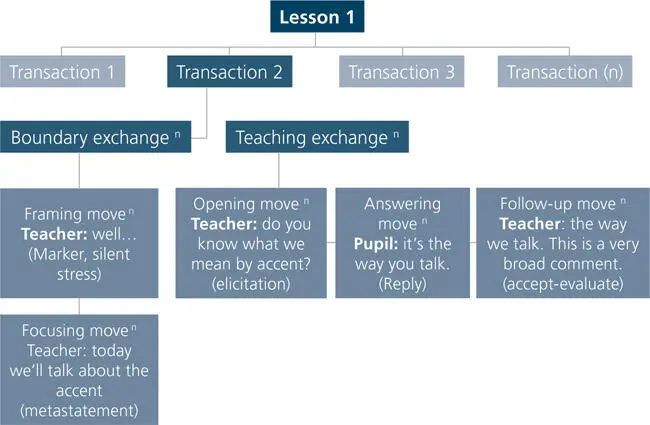

Thus, there are a finite number of moves that are contained in a finite number of exchanges. Therefore, for Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) “Framing and Focusing moves realize Boundary exchanges [that are understood as exchanges with no pedagogical value at all, but they rather function as transitional exchanges between Teaching exchanges which are said to have pedagogical value] and Opening, Answering and Follow-up moves realize Teaching exchanges” (Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975, p. 44). It should be recalled that the lesson is at the top rank of the discourse level. The lesson, understood as a complete pedagogical unit, is made of transactions consisting of exchanges. Figure 1 illustrates comprehensively the authors’ abstract system of analysis of the discourse level.

Figure 1. Sinclair’s and Coulthard’s System of Analysis of Classroom Discourse.

Figure 1 can be read using either a bottom-up or a top-down approach. I will explain it using the former. The teacher’s utterances ‘Well…’ and ‘Today we’ll talk about the accent’ structure, in the form of a marker, a silent stress and a meta-statement. They comprise two kinds of moves: respectively, the framing move and the focusing move. These two moves realize one possible boundary exchange in a lesson or a number of them. The moves of any pedagogical exchange are realized by acts, indicated in parentheses in the figure above. The teacher is making an opening move or initiation when eliciting an answer to ‘Do you know what we mean by accent?’ At this stage, a pupil uses an act of reply, stating ‘It’s the way you talk’ configuring the answering move or response. Finally, the teacher introduces an acceptance act and an evaluative act when saying ‘The way we talk/This is a very broad comment.’ This is the follow-up move or feedback. As a result, the opening, answering, and follow-up moves cause any pedagogical exchange or a number of them. A group of pedagogical exchanges combined with a number of boundary exchanges make up the lesson, which is Sinclair and Coulthard’s unit of study.

Sinclair and Coulthard’s study was conducted in an English-speaking mother-tongue environment with a class of primary school learners. Their main findings, after analyzing two types of texts from their corpus—a complete lesson and an excerpt from a lesson—are conducive to generalizations implying that discourse analysis studies should have a well-designed system of analysis. Additionally, they found out that most moves are initiated by teachers, and in that sense, a rigid structure of a class does not necessarily guarantee learning. Further studies in this area should be conducted. These two linguists also outline educational research topics or areas based on discourse analysis. These areas imply finding out how linguistic and social behavior are linked within the classroom, how to analyze different teaching styles, especially when the lesson structure is not rigid, how to give an account of peer talk, how to conduct cross-cultural studies, and how to cope with different kinds of discourse.

Discourse analysis applied to classroom language started generating more questions based on Sinclair and Coulthard’s (1975) findings. Scholars interested in the topic began to apply their model and to theorize about classroom language. One of those scholars was Cazden (1988) who defined the study of classroom discourse simply as “the study of that communication system” (Cazden, 1988, p. 2). Before Cazden’s study, however, the sociologist Hugh Mehan had published a major work on classroom discourse analysis.

Mehan (1979) offers a considerably critical piece of work on teacher-led lessons for the moment in which his research report was published during the late 1970s. It is interesting to notice that some sociolinguists replicated the structural analysis of classroom talk proposed by Mehan at that time. Mehan, as mentioned above, is a sociologist himself. His study was conducted in a public school where Cazden (1988), who has a transformational grammar background, was the leading teacher of the mixed grade 1-3 classroom being investigated (in California, USA). Mehan’s study “examines the social organization of interaction in an elementary school classroom across a school year” (1979, p. 1). The author adopted a constitutive ethnographic approach: “constitutive ethnographers study the structuring activities and the social facts of education they constitute rather than merely describing recurrent patterns or seeking correlations among antecedent and consequent variables” (Mehan, 1979, p. 18). The researcher, in order to frame his study from a theoretical point of view, followed four criteria because according to his analysis “the constitutive analysis of structuring school […] aim[s] for: 1) retrievability of data, 2) comprehensive data treatment, 3) a convergence between researchers’ and participants’ perspectives on events, and 4) an interactional level of analysis” (Mehan, 1979, p. 19).

Читать дальше