Consequently, the behavior and development of complex systems are very difficult to predict. This is also evident, for example, in the case of a pandemic. Whereas virus propagation can be definitively modelled under stable (i.e., “biological,” laboratory-based) conditions, this is more complex for the living world where many system levels interact. Even at the biological level, nature is open-ended. Viruses can be carried into a country or jump between living beings. Human behavior results not only from events on the biological level, but also very much from those on the economic, political, and societal level (strength of the economy, trust in authorities, local culture of dealing with each other).

Similar interactions apply to companies if, for example, a business model that is consistent at the logistical and financial levels cannot be implemented because external influences (e.g., political conflicts) cause resistance at the social and emotional levels. Systemic analyses help to describe, model, and thus explain how companies and organizations behave in their environment.

1.5.2 Process View of Organizations

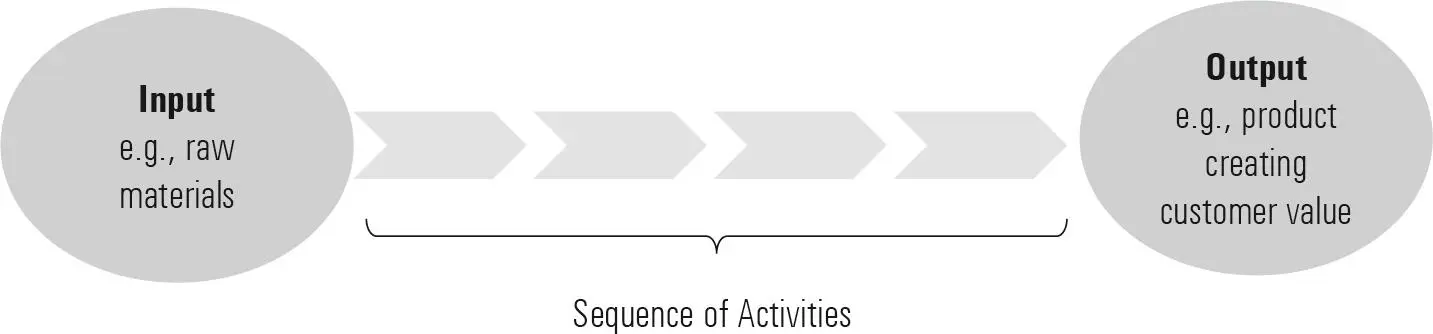

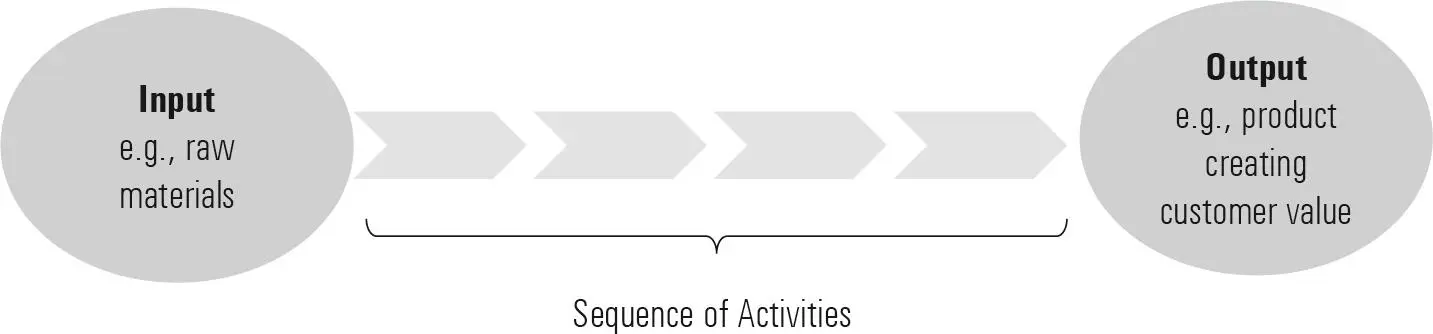

[41] Processes can be defined as a sequence of activities leading from one or more types of input to an output (see Porter, 1985) (Figure 1-4). The foundation and primary process of every organization is value creation. An organization defines itself in terms of its services. This orientation toward the customer value of a service is represented by the business processes at the heart of the St. Gallen Management Model (SGMM).

A value creation process must increase value between input and output (Figure 1-11). This value can be material (i.e., monetarily calculable) because input and output are traded on markets and thus have a price. This value creation can be distributed to stakeholders or used to further develop the company (Bieger, 2019). Value, however, can also be intangible, for example, when volunteer work enables care services or cultural creation unavailable in this quality on the market. Value is then designated, for example, via the required input (i.e., the amount of work) (for a critical exploration of value concepts, see Mazzucato, 2018).

Figure 1-11: Illustrative Process Chain

Besides the necessary steering of process activities (coordinating capacity and quality, etc.), the following aspects of value creation processes are of interest from a management perspective:

– Value chains tend to be restructured on an ongoing basis. Environmental changes (e.g., new technology or changed prices for input factors) mean that activities need to be carried out differently or that value chains may even need to be reconfigured. For example, “print on demand” makes stocking spare parts unnecessary.

– [42] Value chains tend to become increasingly differentiated and specialized as a result of the underlying “economies” (e.g. economies of scale).

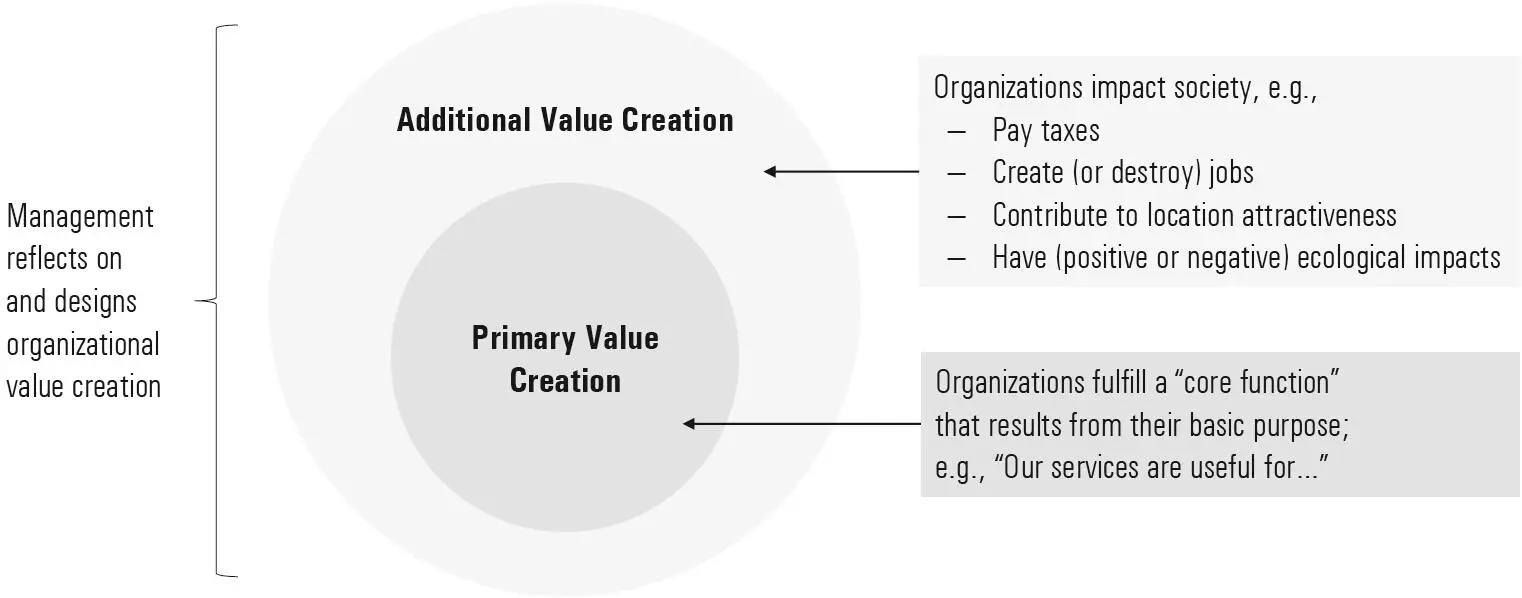

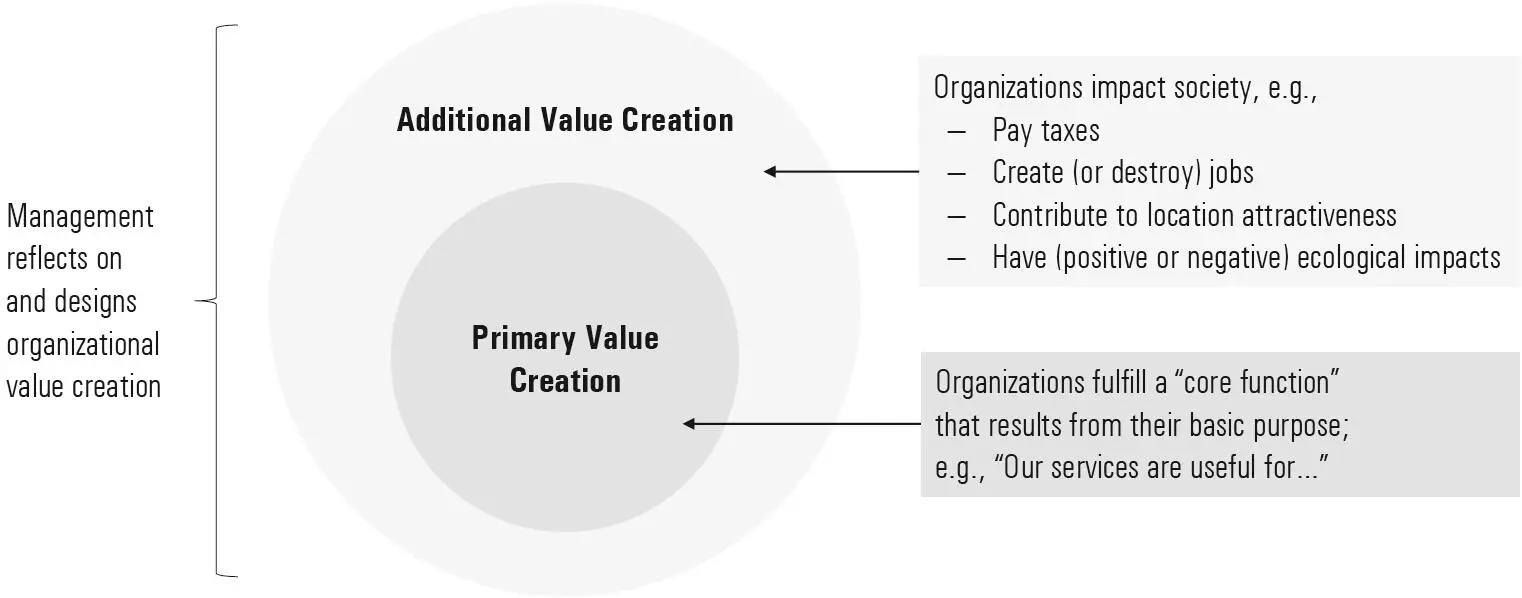

– Additional value (e.g., boosting the attractiveness of a region by creating jobs and paying taxes) is created beyond primary value creation (Figure 1-12).

Figure 1-12: Differentiation of an Organization’s Primary and Additional Value Creation.

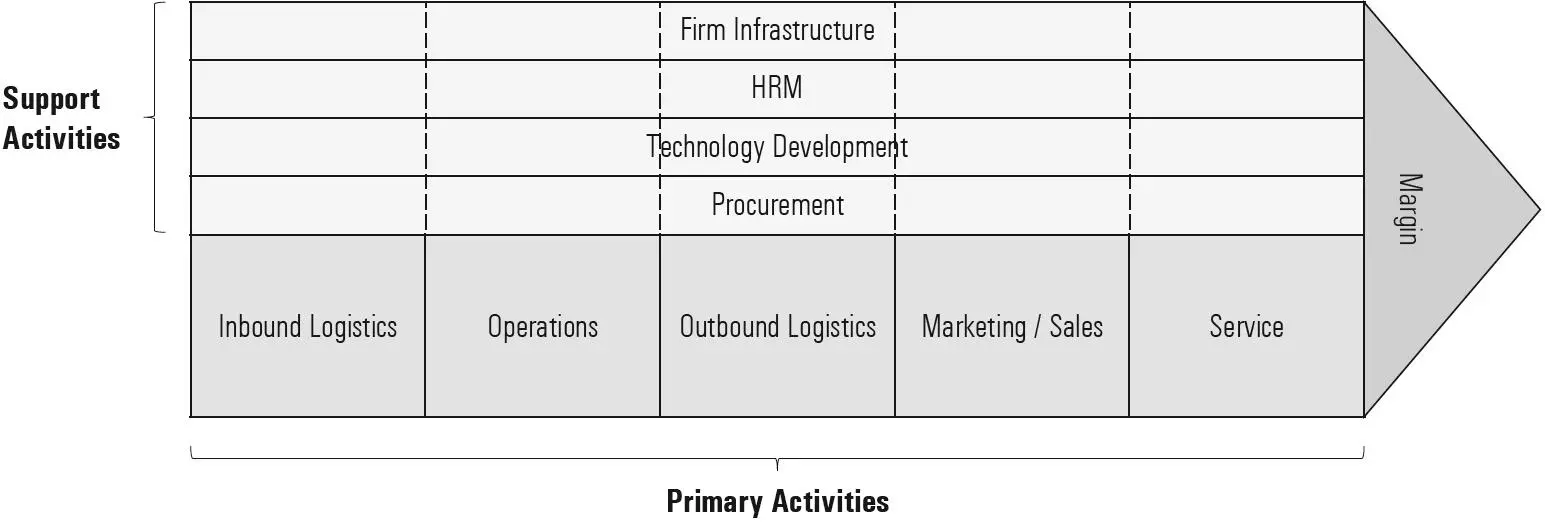

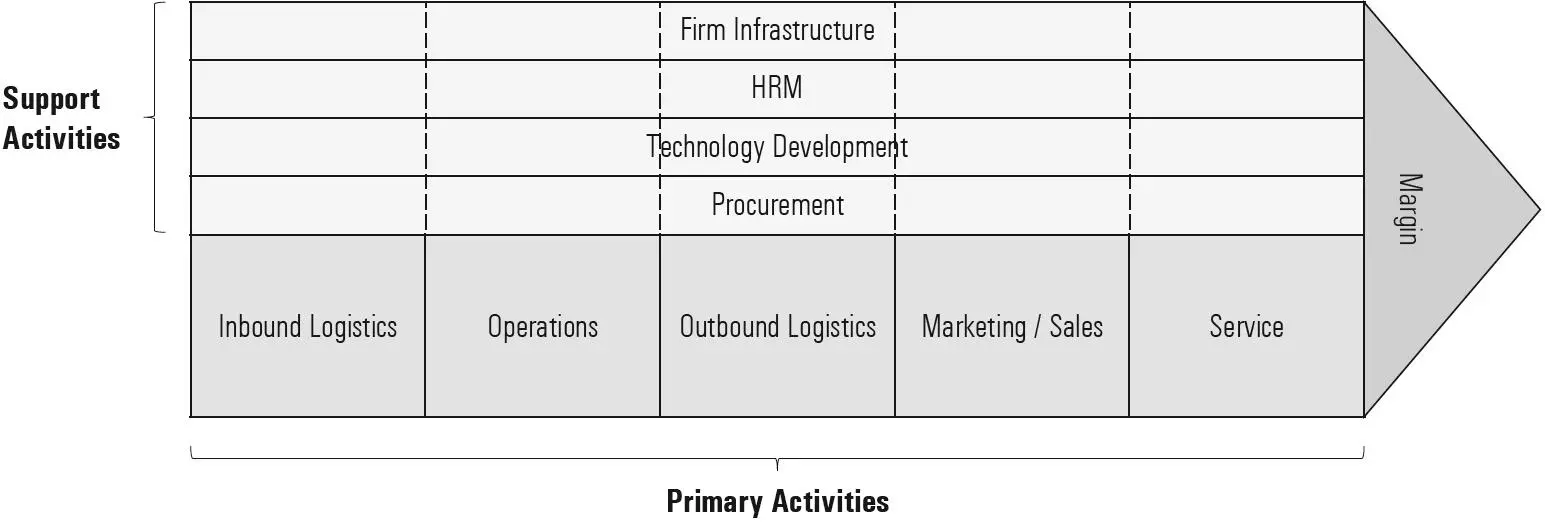

A process view of a company helps to optimize interactions between individual processes across functions. Porter’s (1985) basic process model of a company distinguishes primary and supporting activities. The former focus on the value creation process, while the latter establish the prerequisites (Figure 1-13).

Figure 1-13: The Value Chain

Source: Porter (1985, p. 37)

[43] For complex projects (e.g., purchasing a subsidiary) but also for complex service processes (e.g., recruiting a new executive, installing manufacturing machinery), process planning models are developed with the help of different techniques.

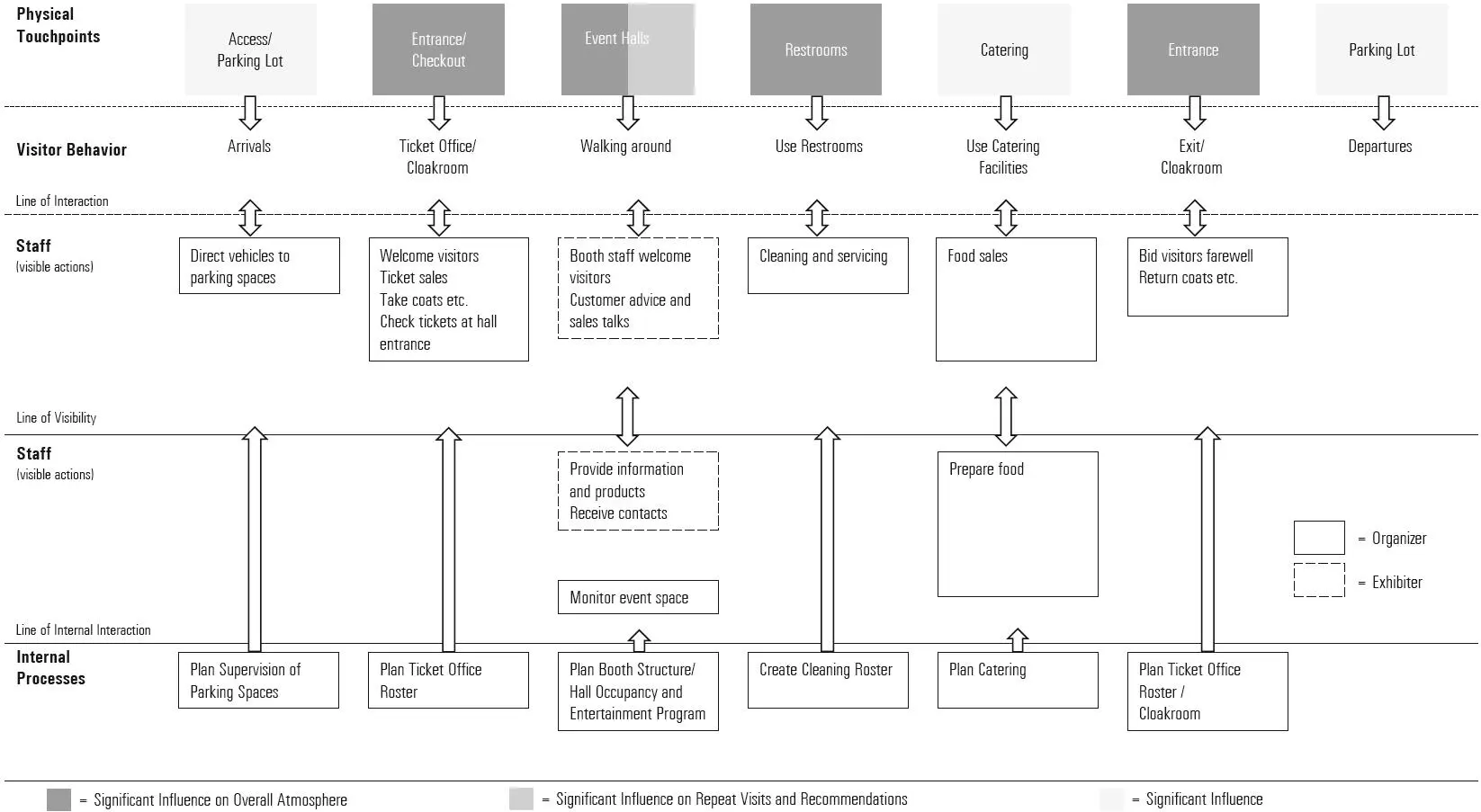

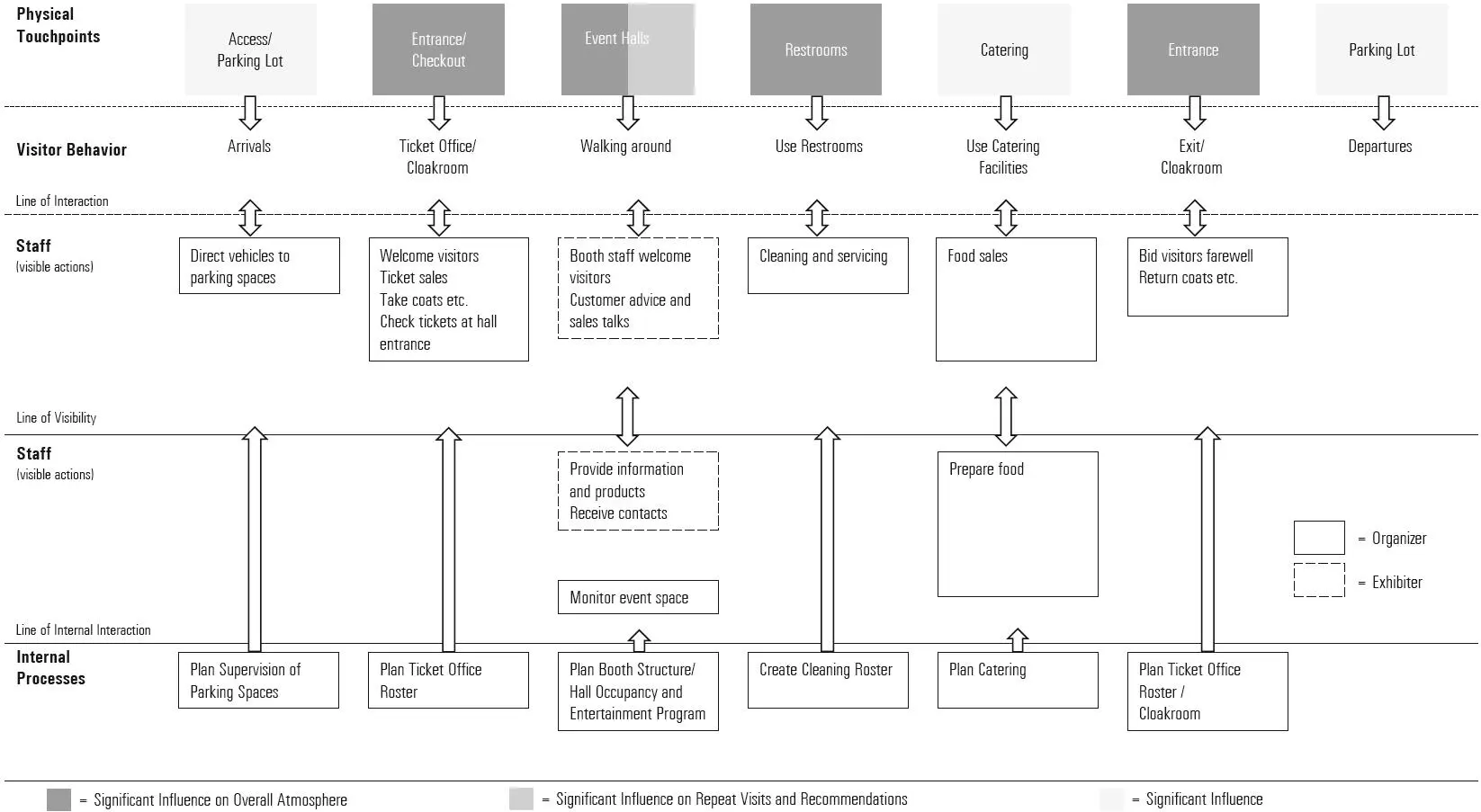

So-called “service blueprints” are often used to represent to-be processes (ideal situation). This normative design instrument is used to show various levels as well as a so-called visibility line. At the top are the customers or the physical points of contact with them (Figure 1-14).

Figure 1-14: Illustrative Service Blueprint: The Example of a Public Trade Fair

Source: Wiedmann and Kirchgeorg (2018, p. 56)

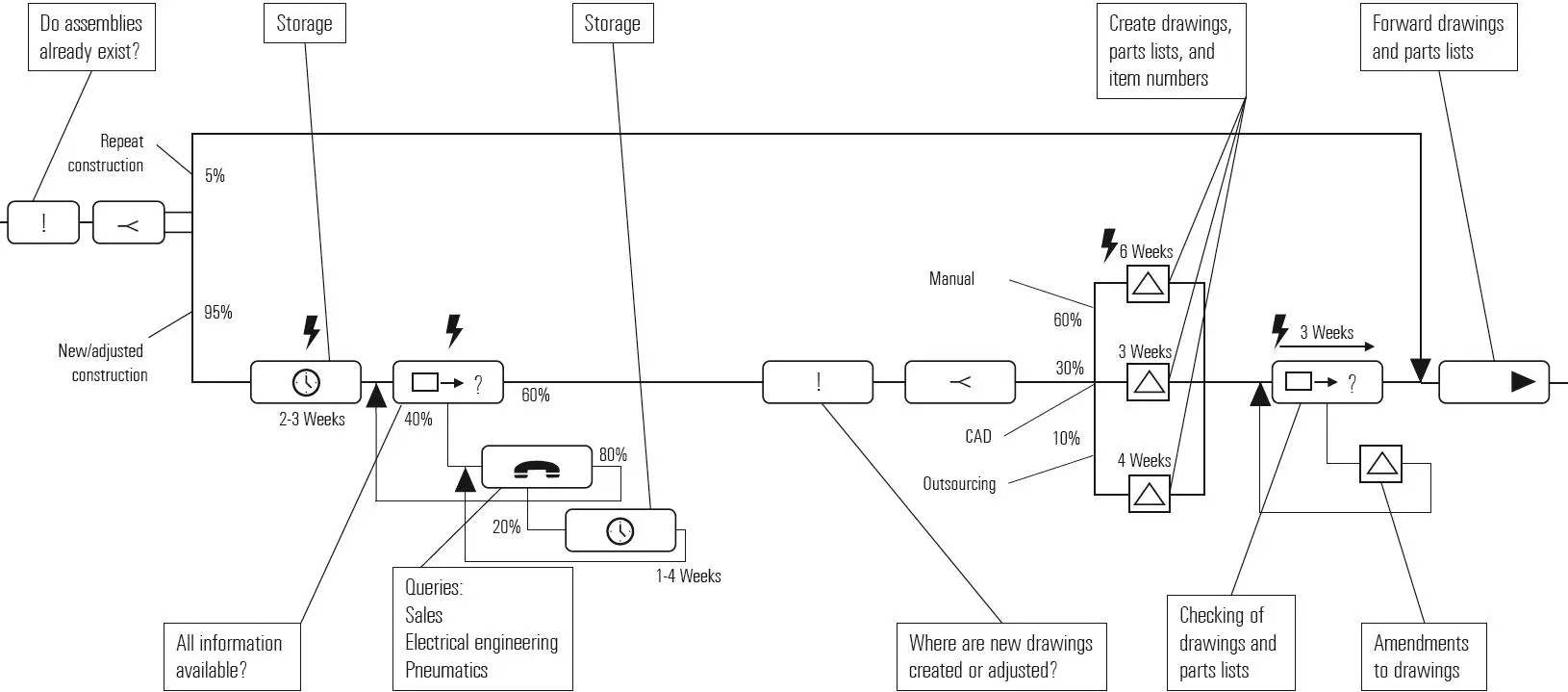

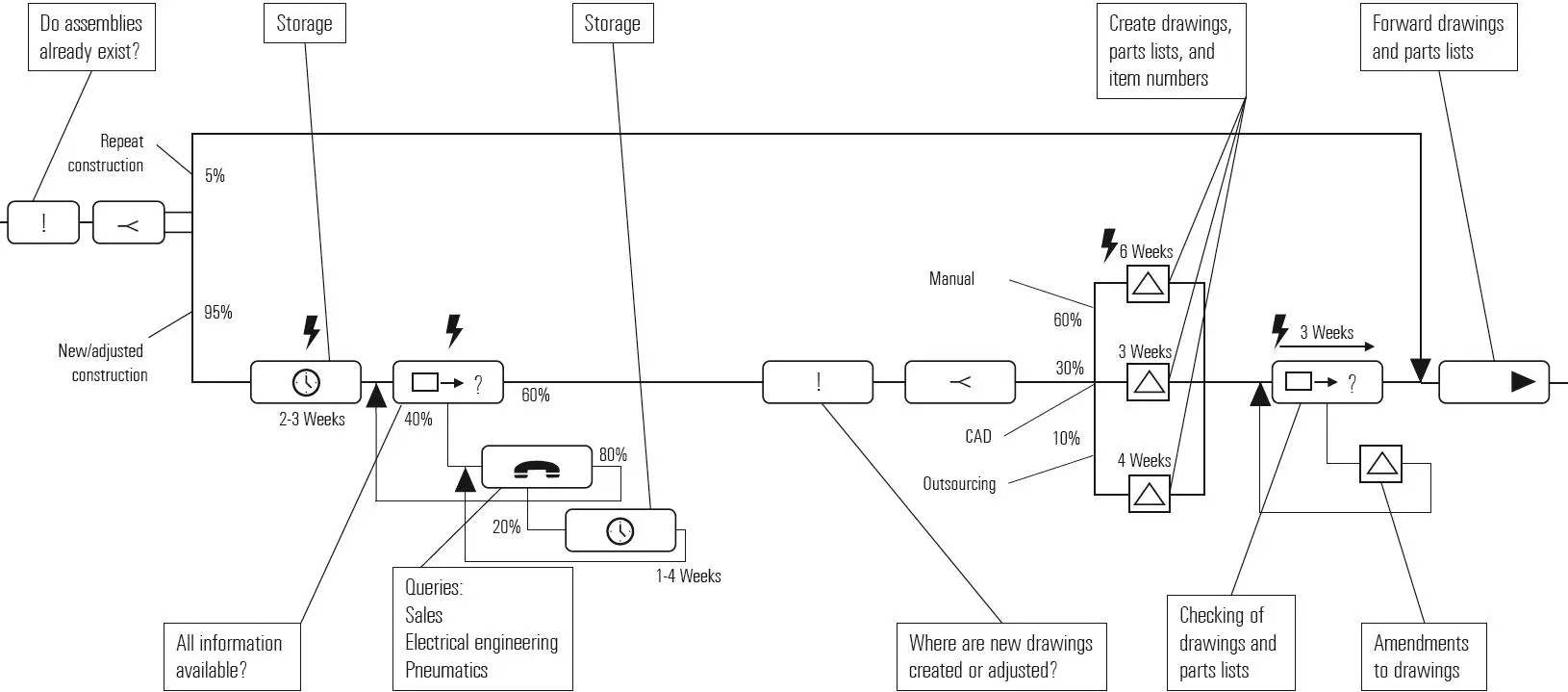

[44] Process maps, for example, can be used to show as-is (i.e., real) processes. These descriptive recording instruments enable empirically recording processes (i.e., as existing in reality) and displaying them as a process diagram (Figure 1-15). These process maps provide the basis for continuously improving such sequences of activities, because they illustrate the interdependencies of these activities.

Figure 1-15: Illustrative Example of a Process Map (ITEM-HSG Project Documentation)

Source: Rüegg-Stürm and Grand (2020, p. 83)

1.6 Types of Companies and Organizations

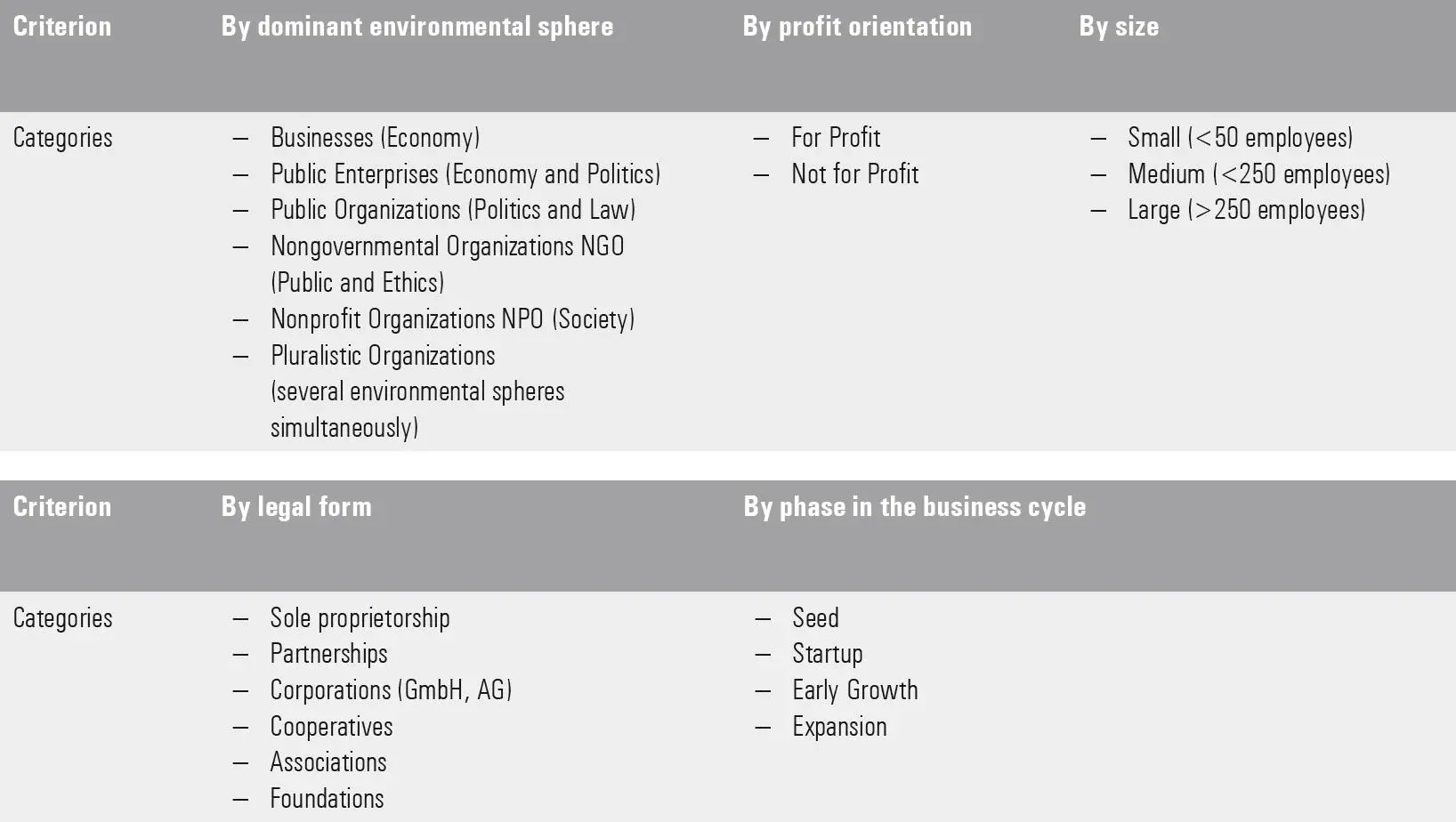

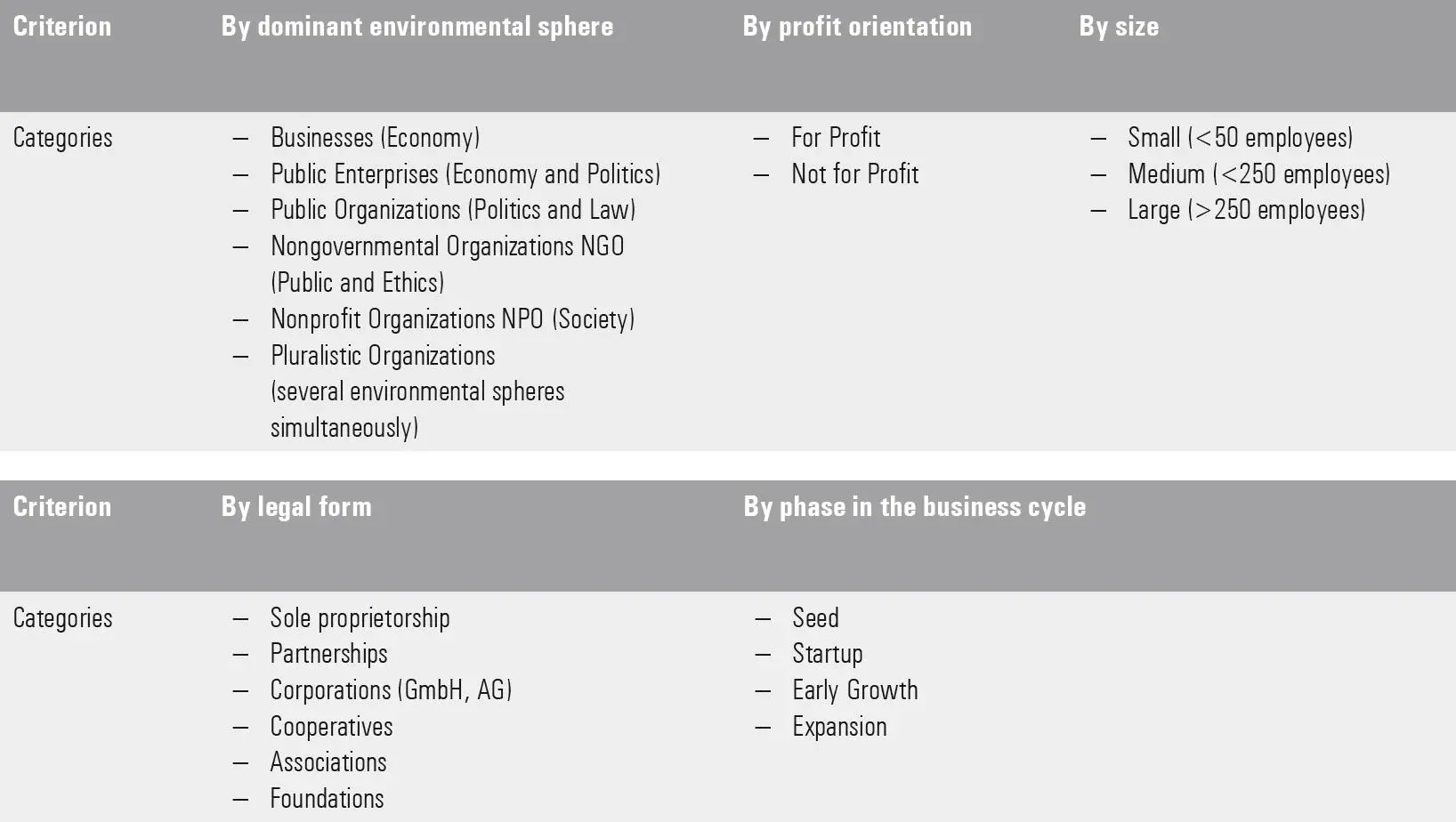

[45] How the management tasks described above are prioritized and performed, and how the corresponding questions are answered, depends not only on the environmental context but foremost on the type of organization. Various criteria (Figure 1-16) can be used to typify organizations (based on Rüegg-Stürm & Grand, 2020, p. 36; Thommen, Achleitner, Gilbert, Hachmeister, & Kaiser, 2017, p. 25).

Figure 1-16: Various Criteria and Their Categories Used to Typify Organizations

Source: based on Rüegg-Stürm and Grand (2020, p. 36); Thommen et al. (2017, p. 25)

[46] The type of organization and, above all, its economic (i.e. profit) orientation, significantly impacts the performing of management tasks and the force fields arising in the process. This is exemplified by the weighting of individual stakeholder interests.

Besides the differentiation according to the dominant environmental sphere, distinguishing organizations by profit orientation — “for profit” versus “not for profit” — is very important. Private companies seek profit, mostly directly or indirectly. They use their profit to compensate the risk capital needed, for example, to pursue risky innovation activities (e.g., when listed pharmaceutical companies research, test, and launch new drugs). Nonprofit enterprises mostly pursue social goals (e.g., NGOs operating in the field of development strive to combat poverty, while private foundations promote cultural projects). Not-for-profit companies are often financed by return on capital and donations, but also by their service fees (e.g., project services) or subsidies. In order to raise funds, they must document their success in attaining their goals in order to attract potential funders. For example, in 2019, the Bergwaldprojekt foundation had a total of CHF 1,726,754 in donated funds, which it invested in mountain forest conservation projects for 12,275 working days (Varinska, 2019).

Читать дальше