ROGER FELL ON IT

ROGER FELL ON IT

“He’s two pounds if he’s an ounce,” said Captain Flint. “You’ve got one of the grandfathers. Beaten the lot of us. Float-tackle and all.”

Titty’s and Roger’s big fish was far too big to go in the basket. They carried it between them in Captain Flint’s landing-net.

“Isn’t it a pity mother isn’t coming to tea to-day?” said Titty.

“She ought to see it,” said Captain Flint, and in the end they sent it to Holly Howe. Captain Flint was to leave it there on his way up the lake. Very soon after tea he was off.

“I don’t want to be late,” he said. “Those two pirates were twenty minutes late for lunch yesterday. They ran into a calm. Not their fault, but their mother hadn’t heard the last of it when I ran away this morning.”

“Ran away?” said Titty.

“Well, hurried,” said Captain Flint. “I had to be down here early if we were to get going with the new mast.”

“Will the Amazons be coming to-morrow?” asked Susan.

“Don’t tell us, if they’re going to make their surprise attack,” said John.

“From what I heard I don’t think they’ll be able to get away. No, I’m sure they won’t be here to-morrow. But I’ll do my very best for them the day after that.”

“Perhaps it’s a good thing they can’t come to-morrow,” said John. “There’s a lot to do on the mast.”

“They don’t think it’s a good thing,” said Captain Flint.

“I think it’s horrid that they can’t come,” said Titty.

“So do I,” said Captain Flint, “but it can’t be helped.”

The big trout was wrapped in bracken, together with a bit of paper on which Titty had written, “Mother. With love from Titty and Roger”; and Roger had written, “We caught it ourselves.” For a moment, indeed, he found it hard to say good-bye to the fish and to see its rounded, spotted sides for the last time, but, after all, mother was going to have it for supper, probably, and Captain Flint could not wait. Roger took a last look, and then held the bracken leaves together while Captain Flint made a neat lacing round them with string so that the big trout made a very handsome parcel.

Captain Flint left the rod and flies, a cast or two and the net and basket for John and Susan to look after, and they were carefully stored in Peter Duck’s. “Don’t waste time fishing the tarn unless there’s a good southerly wind like to-day’s,” he said as he went off. “You’ll do much better in the beck.”

There was a little gloom that evening at the thought of the native trouble that was bothering the Amazons, but it was difficult to think of fish and trouble at the same time, and Susan had more helpers than she needed when she was cleaning the little trout for supper. Each fish was admired, though no one could be sure which was John’s first fish and which Susan’s. “I wish we’d caught some of them,” said Roger, but John said he was a greedy little beast, seeing that he and Titty between them had caught a trout nearly as big as all the others put together. The sizzling and spitting of the boiling butter as Susan fried the trout in batches over the camp-fire reminded them of last year’s perch fishing.

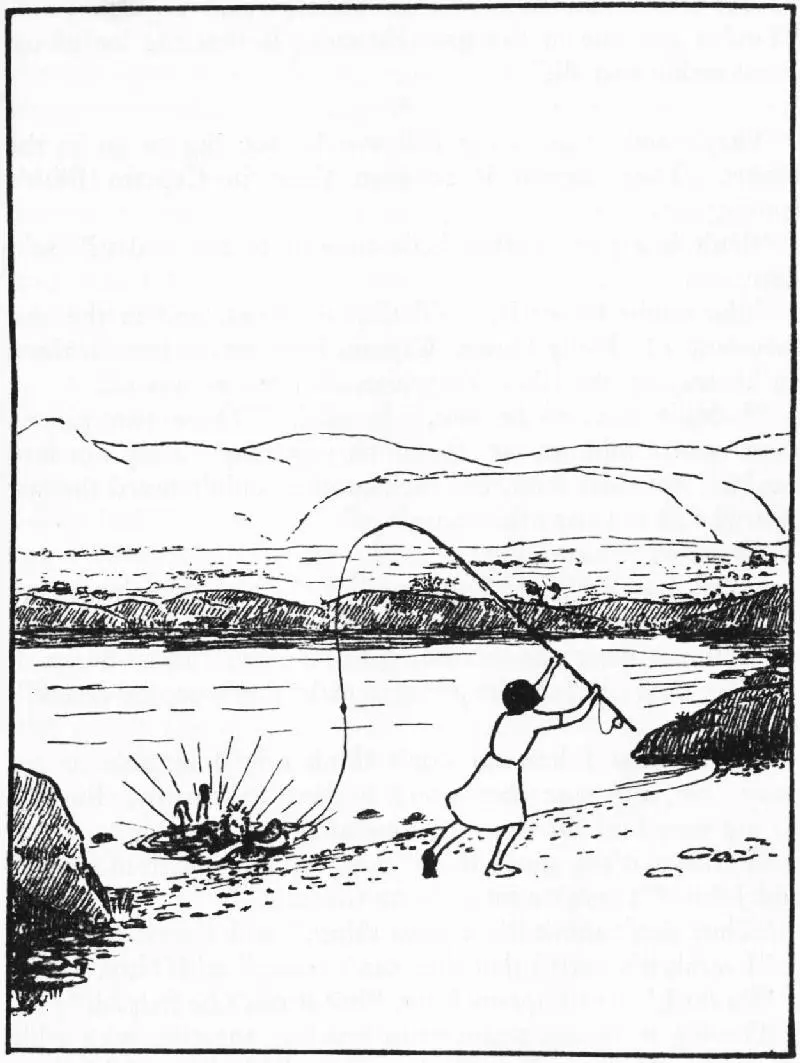

For the next two days Roger could think of very little but trout. He spent that evening, between supper and bed, partly in sliding down the Knickerbockerbreaker and partly in turning over the loose stones at the side of the beck, looking for worms and mostly finding ants. Next morning, after going down with Susan for the milk and being darned, he went up again to Trout Tarn, and tried to tempt another monster, but caught nothing, and gave it up when he found that Titty, fishing the little pools of the beck just below the tarn, and using the less important worms, had caught four little trout in a way John had shown her before going down to work on the mast. After dinner he too began fishing the pools without a float, and by the time John came up from the cove, at the end of a hard day’s work on the mast, bringing with him mother and the ship’s baby, who had rowed into the cove in time to come up to Swallowdale for tea, Roger had himself caught two, and there was a good deal of hurry in getting them cleaned and cooked in time for mother to try with the bunloaf and butter.

Yesterday’s big trout had been boiled at Holly Howe, and had made a supper for mother and nurse, and Mr. and Mrs. Jackson had had some too, and there had been some for Bridget to have after her porridge at breakfast. Mother said it was the biggest trout she had ever seen in England, though she had seen much bigger in Australia and New Zealand. The ship’s baby was delighted with the ship’s parrot’s private perch. Mother liked the bathing-pool. She had been all up the valley before, at last, they showed her its secret and pulled aside the heather from the doorway and gave her Susan’s torch and told her to go in to see Peter Duck’s cave. What she said about that pleased everybody.

“Any explorer would be glad if he’d found a cave like that.” This pleased Titty and Roger. “It’s a very neat and well-kept larder.” This pleased Susan. “It wants nothing but a stone table.” (John at once decided he would make one.) “And what a place to hide in.” This pleased all of them. “But no sleeping in it.” Susan explained that nobody was going to sleep in it except the parrot. “And Peter Duck,” said Titty.

“Of course,” said mother. “Hullo. What’s this? Ben Gunn?”

She was looking at a patch of wall lit by Susan’s torch, the very patch on which Captain Flint had carved the name “Ben Gunn,” so many years before. Another name had been added underneath the first and a bracket joined the two.

“You see, Ben Gunn belongs to Captain Flint, and Peter Duck is ours,” said Titty.

The others peered at the wall. This is what they read:

| BEN GUNN |

} |

|

|

} |

PARTNERS |

| PETER DUCK |

} |

|

The letters were not all of the same size. Nor were they very straight. But it would have been hard to do better, working with a knife by the light of a candle lantern.

“But when did you do it?” asked Susan.

“When you and Roger went for the milk this morning,” said Titty, “and John had gone up to the Watch Tower Rock.”

“The Watch Tower Rock?” said mother. “What’s that?” and they took her up there and she lifted the ship’s baby up to John and then climbed up herself and looked back over the lake to Holly Howe far away down below, and up over the moor to the big hills. They told her which of them was Kanchenjunga and how some day they were going to join the Amazons and climb that mountain together.

“Poor dears,” said mother, “from what I hear they’re having rather a poor time.”

“Horrible,” said John. “We saw them out driving.”

“With gloves on,” said Titty.

“What’s the great-aunt really like?” asked Susan.

“Didn’t she come to tea to make friends the day after we sailed away to Wild Cat Island?” said Titty.

“I wouldn’t say she came to make friends,” said mother. “It was a curiosity call. She made Mrs. Blackett bring her because she wanted to know what we were like.”

“But didn’t she make friends when she saw how nice you are?”

Mother laughed.

“Perhaps she didn’t think so.” She would say no more about the great-aunt, and all the rest of the time she was up on the Watch Tower Rock and at tea in Swallowdale and on the way down to the cove, when all the explorers went with her to see her safely through the jungle, she talked about fishing and about caves and about camping in the Australian bush, where there were much worse snakes than adders.

Читать дальше

ROGER FELL ON IT

ROGER FELL ON IT