Chapter XV.

Life in Swallowdale

Table of Contents

The explorers slept rather late in the morning. When they waked there was a rush to the head of the valley to see if the dam had been washed away. It had not. Not a stone of it had stirred, and everybody had a dip in the new bathing-pool. They had come back and Susan was just reminding them that it was a long way down to Swainson’s farm, and that somebody must fetch the milk before they could have breakfast, when a cheerful voice said, “Well, you have made yourselves comfortable. Did you have a good night?” and they saw Mary Swainson looking down on them from the top of the slope above the cave. She had a milk-can in one hand and a big market basket in the other.

“Rice pudding,” she said, “from Holly Howe. And Mrs. Walker’s coming to tea with you to-morrow and bringing another pudding with her, so you’ve to eat this to-day.”

“Don’t try to get down there,” said John. “It’s slippery.”

But Mary Swainson seemed to know the valley very well. She went a few yards farther on along the edge of it and then came down by a sheep-track that ended close by the bathing pool.

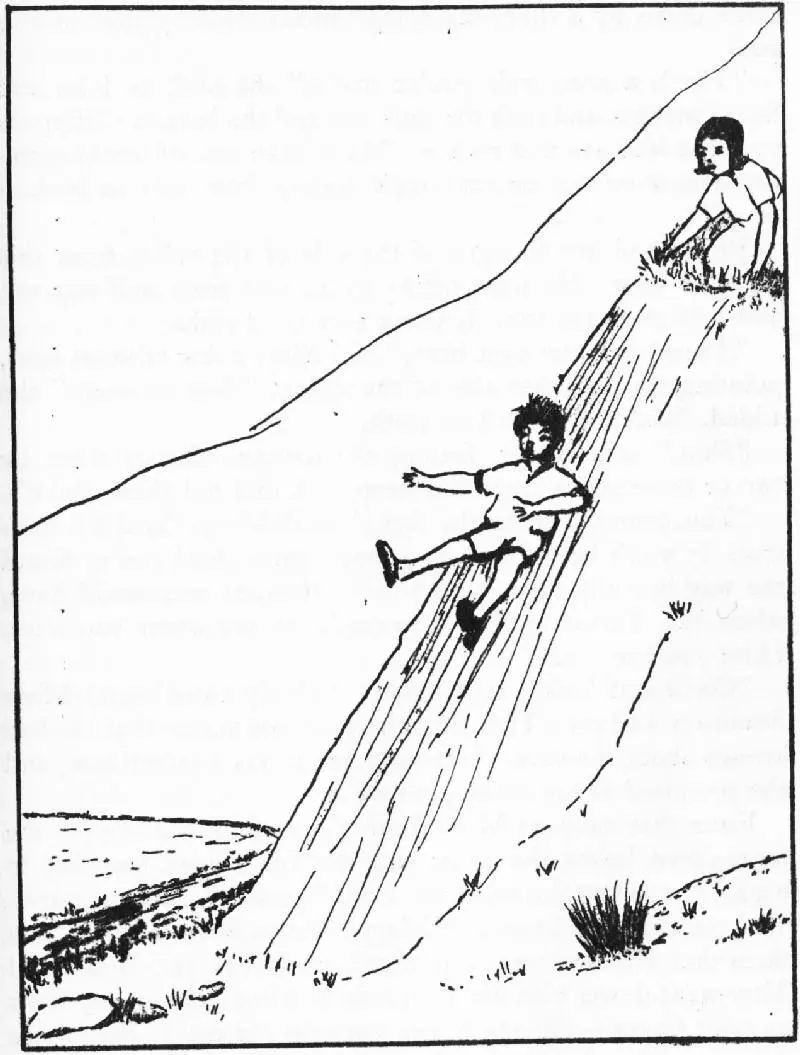

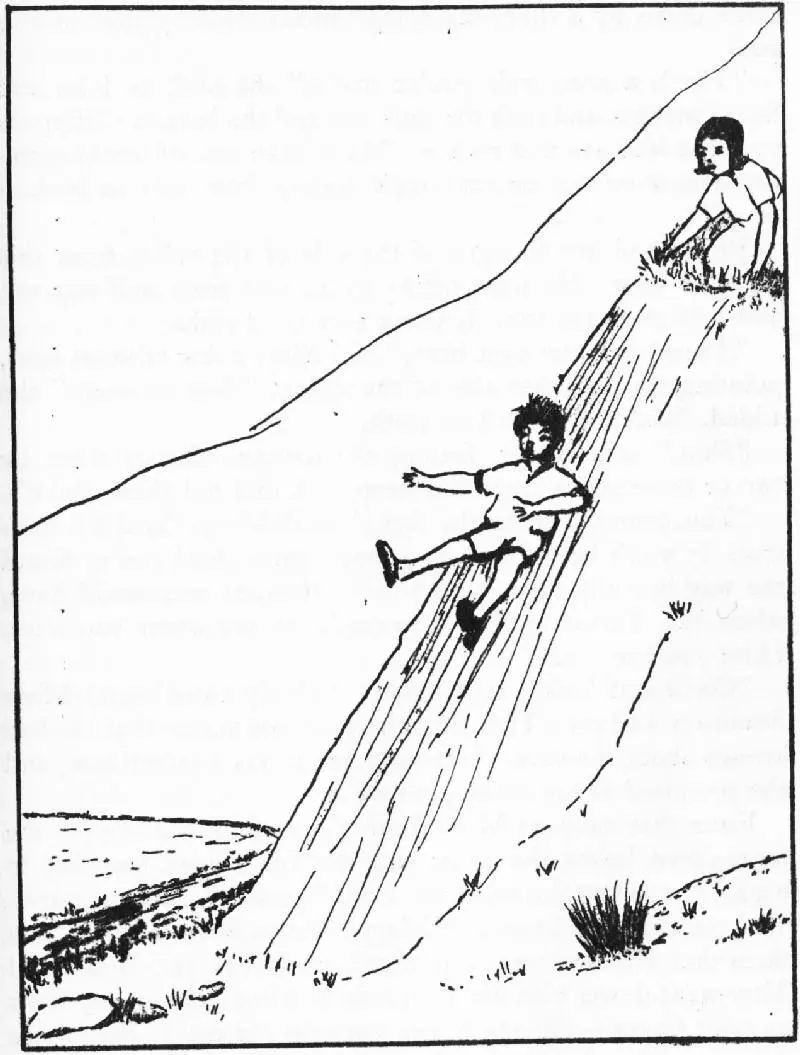

“That’s a good weir you’ve made,” she said, as John and Susan met her and took the milk-can and the basket. “Slippery you may well say that rock is. Many’s the pair of breeches my brothers wore out on that rock sliding from top to bottom of it.”

THE KNICKERBOCKERBREAKER

THE KNICKERBOCKERBREAKER

Roger had not thought of the side of the valley from this point of view. He went off to try it, first from half-way up, and then from the top. It was a very good slide.

“There’s a better over here,” said Mary a few minutes later, pointing up the other side of the valley. “Not so steep,” she added, “and not so hard on cloth.”

“Skin,” said Roger, feeling the damage already done by two or three slides down the steep rock that hid Peter Duck’s.

“You come down to the farm,” said Mary, “and I’ll darn that. It won’t be the first by a long count. And you’ve found the way into the cave, have you? I thought you would have, when Mr. Turner looked in yesterday to say where you were. Have you been in?”

“Come and look,” said Susan. Nobody could mind Mary Swainson, and even Titty thought it did not matter that she had known about the cave. John told her it was a secret now, and she promised to say nothing about it.

From that moment Mary Swainson, though she lived at the farm down below the moor and was busy from morning to night, seemed to the explorers more like an ally than a native. You could always be sure of Mary. She took a cup of tea with them that first morning, and after breakfast Roger, Susan, and Titty went down with her to the farm when John went down to meet Captain Flint to begin work on the mast. Roger was down at the farm next day to be darned again. Mary darned him about twice a day until at last he was tired of the “Knickerbockerbreaker,” which, Titty said, was much the best name for it.

Soon after John had left the cart-track in the wood by the lake and was making his way through the trees to Horseshoe Cove, he heard the noise of a hand-saw. Captain Flint was there before him and was hard at work shaping the foot of the mast, making it exactly like the foot of the mast that had been broken, so that it would fit cleanly into the socket in the keelson. That was soon done. John had brought the shaping plane down from the camp in his knapsack, and now Captain Flint showed him how to use it. The plane was curved, so that it would take shavings off a rounded surface as evenly as an ordinary plane takes shavings off a plank. He had also brought down the callipers, big pincers that opened and shut and had a small screw to keep them just as much open or as much shut as you wanted. Captain Flint showed John how to measure the same distance along both masts, and then how to fix the callipers just so much open that both curved points touched the wood when they were used to measure the thickness of the old mast. Then he set to work planing down the new mast evenly, all round, until it too exactly fitted between the points of the callipers.

“Remember one thing,” he said. “Never take off too much. If you take off too little you can always take off a bit more, but if you take off too much you can never put it back.”

They worked hard at the mast all that morning until nearly dinner-time, when the others came from the farm and told of how they had been singing choruses with old Mr. Swainson, and sewing a patch into Mrs. Swainson’s new patchwork quilt, and seeing pigs and calves and a foal, and the biggest tabby cat that ever was seen in the world. “He follows Mary about, but she isn’t going to let him come near Swallowdale. But she says he’s frightened of parrots, so it wouldn’t matter if he did come.” And, of course, the mate invited Captain Flint to stop for dinner, and he said he would be delighted and had indeed brought five pork pies from Rio and five fruit pies to match, which he hoped would not come amiss. He brought the parcel with these good things in it out of the shade of a bush where he had put it to keep cool, and took a fishing-rod, a fishing-basket and a landing-net out of his boat. He put the parcel in the basket for easy carrying.

“I thought of going up to Trout Tarn after dinner,” he said, “and I’ll show you how to cast a fly.”

“Let’s all fish,” said Roger.

“You won’t do much in the tarn except with fly,” said Captain Flint, “but if you had a good worm or two you would soon get trout out of the beck.”

“We’ve got our fishing-rods,” said Roger.

“Well, see what you can do in the way of worms.”

It was during that dinner in Swallowdale that Roger asked Captain Flint the question that for one reason or another he had not asked before, though it had been in his mind since the first day.

“Captain Flint,” he began.

“Hullo!”

“Why did you cover up your cannon with a black sheet?”

“To keep strangers and dust off it.”

“A cannon’s better than a sheet to keep strangers off.”

“It didn’t keep you off, did it, when you captured the houseboat and made me walk the plank? Why, I wake in the night even now thinking of the sharks.”

“Well, we wanted you to fire it this year.”

“But I’m not living in the houseboat just now.”

“Why not?”

Captain Flint said nothing just for a moment. Everybody was listening. At last he said, “Look here, Roger, the very first minute I can I’ll be back there with a barrel of gunpowder and you shall come and fire the thing yourself.”

“Let’s go and do it now.”

“He can’t,” said Titty. “It’s the great-aunt. Captain Nancy said so.”

“She isn’t going to stop for ever,” said Captain Flint.

Trout Tarn was nearly a mile beyond Swallowdale, high on the top of the moor, a little lake lying in a hollow of rock and heather. When the Swallows saw it, they wished almost that they had made their camp on its rocky shores. But Titty said that it had no cave, and Susan said that if it was a bother bringing wood to Swallowdale it would be miles more bother bringing it to Trout Tarn. “Two miles more bother. One each way,” said Roger. “And besides,” said Susan, “it would be that much farther from Swainson’s farm. We’d have had to spend all our time fetching wood and milk.” John and Captain Flint were talking of something quite different, and that was the catching of trout, and when Captain Flint sat down and began to put his tackle together, the others stopped talking to look. This was not at all like the perch fishing down on the big lake. There was no float for one thing, no minnow, and no worm. Instead, Captain Flint opened a little tin box, took three flies from it, and gave them to Roger to hold.

Читать дальше

THE KNICKERBOCKERBREAKER

THE KNICKERBOCKERBREAKER