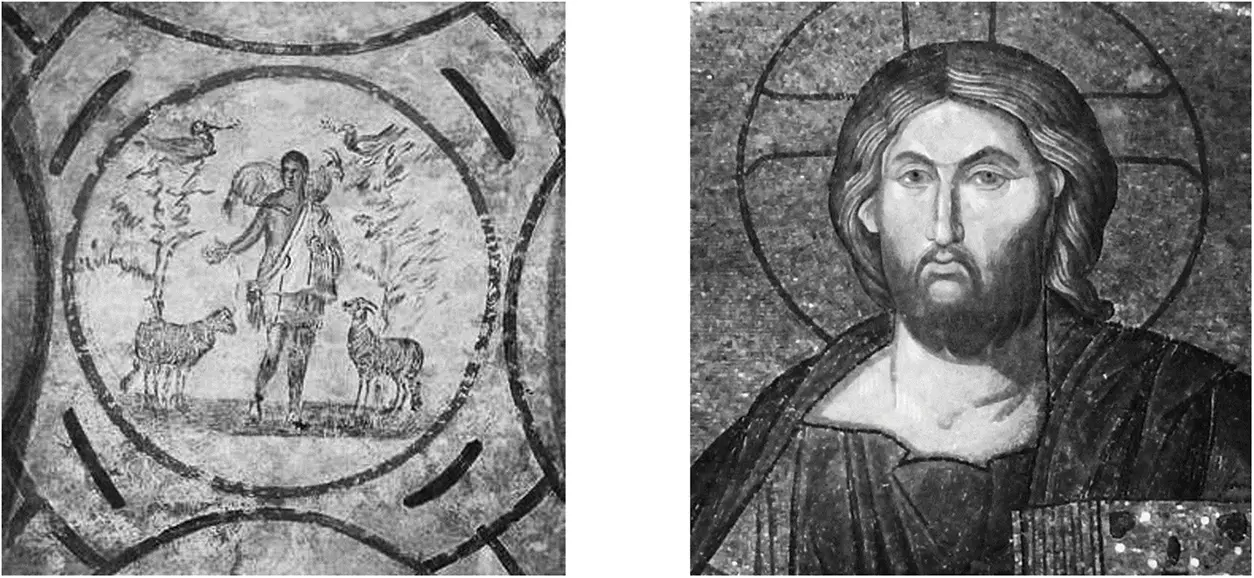

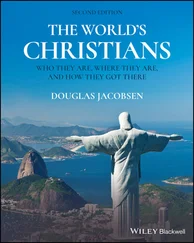

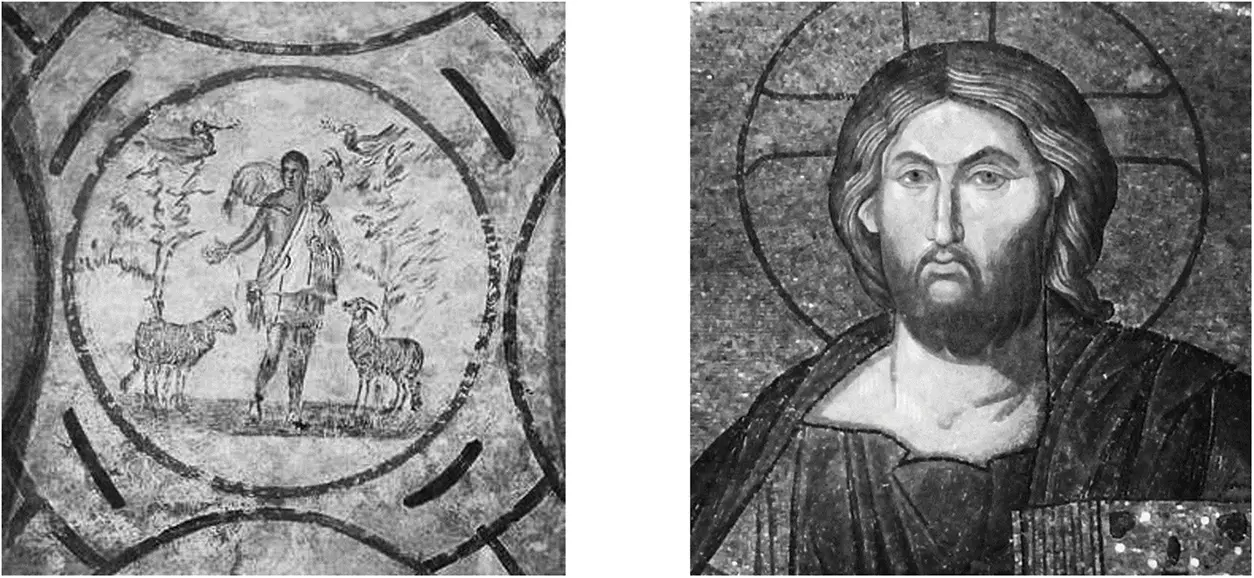

Figure 1.1 Figure of Jesus as a young shepherd (from the catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, third century) and Jesus as a middle-aged judge (from the Chora Church in Istanbul, originally constructed in the later fourth century). Source : Image on left: Joseph Wilpert, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Good_Shepherd_Catacomb_of_Priscilla.

The Council of Chalcedon, held in the year 451, was intended to complete the Imperial Church’s reorganization and its codification of correct beliefs. New guidelines regarding the behavior of monks/nuns and the clergy were announced, and the empire’s churches were incorporated into a hierarchy headed by a handful of super-bishops called “patriarchs.” The council also sought to end speculation about Christ’s ontological identity. The Council of Nicaea in 325 had declared that Christ was both fully divine and fully human but had not explained how the two were related. Chalcedon declared that these human and divine natures were joined, but not merged, in the single person of Christ. This abstraction would have meant almost nothing to ordinary Christians, but it meant a great deal to the bishops and theologians of the Imperial Church because it gave them a firm standard for differentiating truth from error. It was also supposed to unify the Christian movement for all time. But it did not. Instead, the Chalcedonian Creed become a new flash point for division.

Christian Diversity and Unity in the Year 500

The Great Church in the Roman Empire was the largest group of Christians in the world when the Chalcedonian Creed was being written, but it was certainly not the only group. Many Christian sects (marginalized Christian communities that were not legally recognized by either the Imperial Church or the government of Rome) continued to survive out of public sight within the borders of the empire, and groups of Christians outside the Roman Empire were even more diverse. As early as the first century, Christianity had been introduced to southern India via maritime trade routes, and it subsequently became a permanent minority religion within India’s complex social and spiritual environment. Christianity also put down roots in the Persian Empire (now Iraq and Iran) as early as the second century, and Christianity was brought to Armenia and Georgia in the Caucuses (the land between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea) about the same time. Christianity made its way into Ethiopia during the fourth century, and later a group of nine theologically anti-Chalcedonian monks (known as the Nine Saints) fled south from Syria to Ethiopia where they helped to complete the evangelization of the region. Contemporaneously, Patrick was preaching the gospel in Ireland, where Christianity was organized along the lines of the Irish clan system rather than clustering around major urban centers as it did in the Roman Empire.

Christians adopted slightly different Christian identities in each separate region. Armenia, for example, was the first nation to officially embrace Christianity as its state religion, which remains a source of pride for Armenian Christians even today. Christians in Persia were severely persecuted – far beyond the horrors endured by Christians in the Roman Empire – but they remained faithful nonetheless, and joyful perseverance in suffering became a mainstay of their identity. In Ethiopia, where Judaism was historically respected, Jewish ideas and customs remained prominent in the movement. The fact that Christian communities adopted locally unique practices does not mean that they stopped thinking of themselves as belonging to a larger Christian movement that transcends cultural and national boundaries. Then, as now, Christians understood that being associated with a specific local Christian community was fully compatible with viewing other different Christians as siblings in faith. Christian unity was understood to be a matter of mutual recognition and respect much more than it was a matter of strict uniformity of practices or beliefs.

The Roman Imperial Church became the exception to this rule. Rome was a legalistic society, and the Roman Imperial Church imbibed that tendency toward legalism. Romans assumed that there really was one best and proper way to do everything, and the purpose of the law was to identify and enforce that one correct path. In earlier centuries, Christian communities had negotiated their way toward consensual agreements that mitigated conflict but simultaneously allowed reasonable differences to remain. This was true even of the Great Church before Constantine. As the church and the Roman state became more closely aligned, however, it became harder to maintain even a minimal degree of organizational graciousness. The Imperial Church wanted uniformity, and that desire eventually caused the larger Christian movement to snap under the pressure. A Great Division took place, and the formerly diverse but loosely connected Christian movement became three separate and distinct Christian traditions.

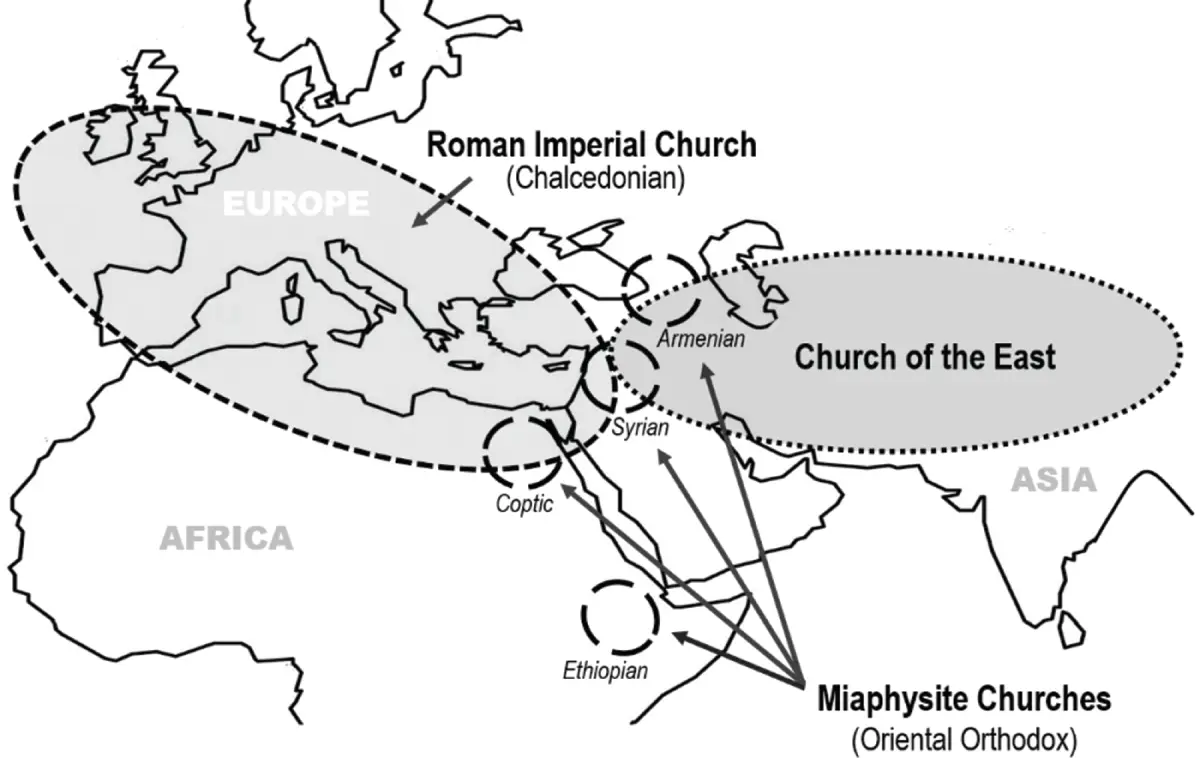

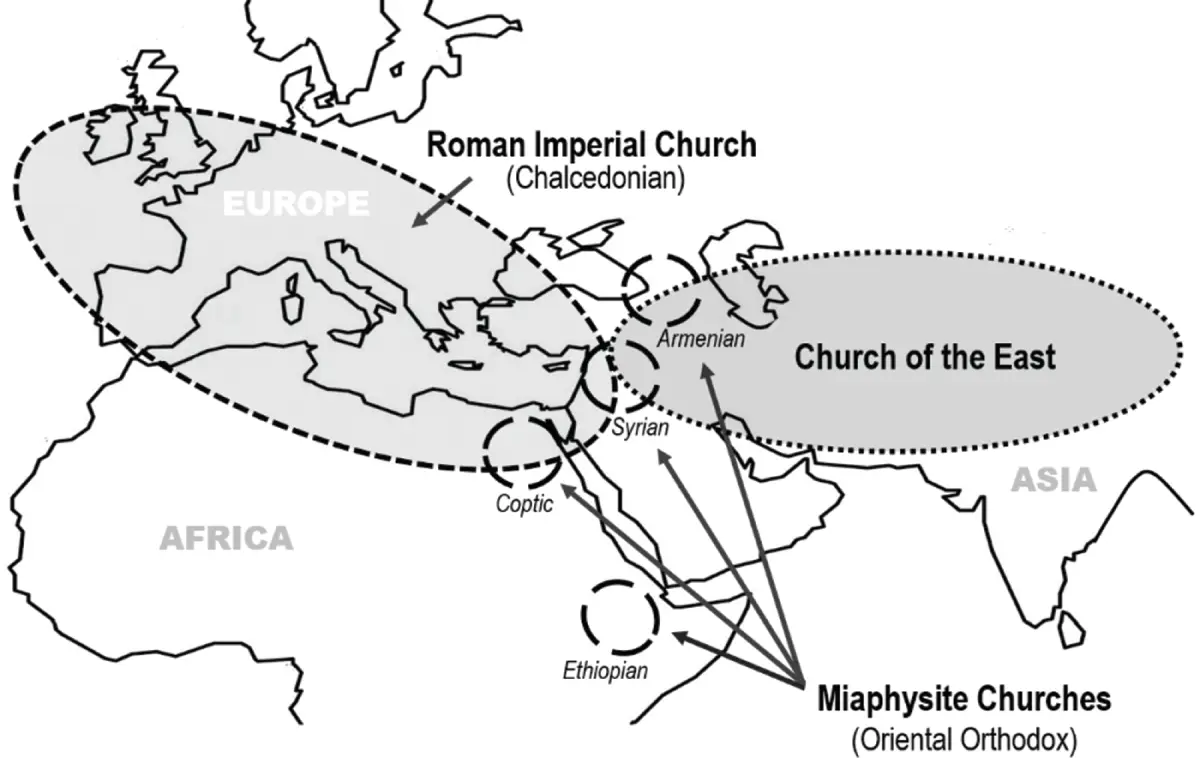

The Great Division took place during the first half of the sixth century, and it changed Christianity from being a complex religious movement into something more like a mosaic consisting of three separate and distinct ecclesiastical tiles. One of those tiles was the Roman Imperial Church, which continued to support the conclusions of the Council of Chalcedon. A second tile took shape in the Persian Empire, where the Church of the East emerged as a newly cohesive network of non-Roman congregations and monasteries. In between these two antagonistic empire-related Christian organizations, a third ecclesiastical coalition arose in Syria and Egypt, forming the third tile of Christianity’s new mosaic. This third group is known as the Miaphysite tradition or Oriental Orthodoxy.

The Great Division is a watershed moment in the history of Christianity, not only because of the three new traditions that were created, but also because these three traditions soon came to dominate the entire Christian movement. Various independent, local Christian groups that had previously gone their own ways now felt compelled to choose sides. Christians in Georgia and Ireland, for example, chose to align with the Chalcedonian tradition, while Christians in Armenia and Ethiopia joined the Miaphysite movement. The consolidation of Christianity into three large and distinct communities, each nurturing its own tradition, permanently reshaped Christianity, and the space for smaller alternative visions of Christianity shrank to almost nothing (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Geographic locations of the three traditions created by the Great Division.

The flashpoint for the Great Division was Christology; the three groups held decidedly different views about who Jesus was and about the purpose of his life and death. Chalcedonians said that the human and divine natures were connected, but neither merged nor confused, in the one person of Christ. Miaphysites disagreed. They asserted that the human and the divine were fully merged and united in Christ, and they were convinced that salvation could occur only because God the Creator had literally felt the pain of death on the cross. It was God’s full identification with the human condition, even to the point of death, that made salvation possible. The idea that God can experience emotions and fully understand the suffering of humankind is something that many modern Christians would agree with almost instinctively, but the Chalcedonian tradition (in opposition to the Miaphysite view) rejected this possibility, saying that God the Father was apatheia (non-feeling) and unmoved by earthly matters. For Chalcedonians, only an unchanging God had the power to guarantee eternal salvation, while Miaphysites believed that only a truly passionate God could and would try to save humankind.

Читать дальше