This is quite a common delusion in Judo. Either Judo students fancy they have to learn a number of throws corresponding to a number of ‘weaknesses’ in the opponent’s position or movement, or else they think they will learn one throw well, and just wait till the appropriate opportunity presents itself. As a matter of fact the basic technique of a throw is only the beginning of mastery; no Judo student has reached expert level at a throw till he knows how to manoeuvre the opponent into it, and till furthermore he can execute it from all sorts of unorthodox attitudes. Before reading further, try the ‘flicker’ at the top right corners of pages 79 to 27 of this book; the attacker is carried right up into the air, but manages to control his opponent’s throw, and comes shooting down into his Taiotoshi. This is the kind of Judo which must be developed, and this is the spirit of attack.

Judo students, from the beginning, must get spring into their movements. Have a look at the section called ‘Tricks of Holding’ and notice how the man rises on tiptoe and sinks right down, then rises again and sinks again, to come up for the last time as he executes the throw. Exercise yourself in thus changing the level in your Judo; if you look through the pictures in this book with this one point in mind, you will have learnt something very useful. Many Europeans hate bending their knees to go down; they would rather keep the knees straight and bend forward to pick something up than bend the knees and go down. Well, in Judo you have to train yourself to bend the knees flexibly and naturally, and at speed. Some experts do a hundred or two ‘squats’ every morning and evening to help them acquire the movement comfortably.

Again study the change of distance in the various attacks; it is no use keeping the same distance from your opponents and hoping they will somehow walk into your throw; you have to chase after them and cover the ground faster than they can. There is a Zen story about a man who was walking in a field one day when he saw a rabbit pop out of its hole suddenly and stun itself against a stake which the farmer had happened to fix there. He took the rabbit home and had it for dinner. Afterwards he used to sit there for hours every day waiting for the same thing to happen again. But it never did. Some Judo students are a bit like this; when they are beginners they manage to get hold of a technique which works when the opponent happens to come right into it. But as they get on they meet better opponents, and then the opponent never walks into the throw again.

We have chosen Taiotoshi to illustrate these principles of movement because it is a throw where the whole body is moved, and where the principle of the throw is not confused by hooking, reaping or sweeping movements of one leg as in many other throws. If you learn the actions of going in to the opponent, chasing, circling, and tricking and so on with this throw, you can apply them to most other throws without more than minor changes in technique.

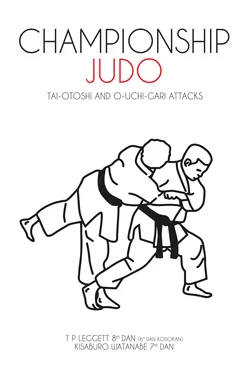

We are using ‘I’ and ‘You’ in this book because it is intended as a straightforward training manual. The technical words are Tori (for the attacker) and Uke (for the one thrown). The other technical words mainly explain themselves: you can see a picture of Taiotoshi on the front cover and in hundreds of places in the book; Ouchi (short for Ouchigari) you can see in the section called The ‘Y’; Kosotogari similarly you will see in Section 21.

The demonstrations in this book are almost all performed by K. Watanabe; no-one can be equally skilled in all Judo movement, but the techniques are mostly his. The pictures are taken from actual practice at full speed (except for a few such as the right-hand slip pictures where the action is not normally clearly visible and which have been posed) with a new camera specially designed for analysis of sports movement. We made a great number of pictures and then selected those where the point to be illustrated appeared from a favourable angle. It is hoped that a realistic effect has been achieved which will give a good notion of movement.

We are grateful to Mr. John Newman, teacher at the Renshuden Judo Club, for making a more vigorous and determined opponent than the lay figure of so many Judo books; thanks also go to Mr. T. Kawamura for the pictures in Section 21, and to Mr. George Kerr, teacher at the Renshuden, and to the members of the Club for help and suggestions.

THE AUTHORS

(1964)

1. How to Build Up Attacking Movement

One purpose of this book is to explain how to build up attacks on Taiotoshi and its main partner Ouchigari, but you can use the method in learning how to master any main throw. Read the whole book quickly once, and then repeatedly run through the flicker at the top right from page 79 backwards to page 27. Then you should have a rough idea of Taiotoshi and Ouchi, and of the spirit of Judo movement.

Your Judo progress depends on three main things : free practice (and contest); formal practice of the movements; study. Get first a rough idea of the movement and keep trying it vigorously and enterprisingly in free practice; don’t fuss too much with detail at this stage. Taiotoshi is called in Japan a ‘choshi-waza’, which means that timing and rhythm are all-important. One day your opponent will go down when you hardly realize you have thrown him, and this will give you an idea of what the throw really is. Study is to help you understand the principles of the throw; formal practice is to help you to begin to ‘feel’ the movement.

After a week or so splashing around with the rough idea, begin your study. Take one point and try to get it fairly accurate; to do this you will have to go fairly slowly, but remember it must still be a Judo movement. If you go too slow your movement will cease to be effective, even against a static opponent.

Don’t expect to get the proper movement right away. Some people hope for the impossible. If you could see the body images in your brain by which you feel position and initiate movement, you would find that while an enormous number of brain-cells are devoted to fine discrimination of the hand for instance, there are comparatively very few for trunk and neck. This means that you simply cannot feel accurately your trunk posture and vary it as you want. For some time your training is in effect establishing new discriminations and control in the body images. As you try free and formal practice, the defective parts of the body images are developing. An ordinary student, for example, takes about one year before being able to stand on one leg for five minutes; in Judo you have to balance on one leg while performing difficult techniques. It takes time, but to develop good feeling and control of the body is of great value in life, and according to the Zen Buddhists, it is of importance in spiritual development as well.

Similarly, most people are hampered at first by a sort of physical timidity, a reluctance to throw themselves into a movement. This too is overcome by practice, and to solve this problem is also a great help in life. Dr. Kano, the founder of Judo, stated clearly that a real understanding of Judo principles can be applied to life as a whole, and when it is so applied, it produces a harmonious development of body, mind and character.

2. Basic Analysis of Taiotoshi

To bring out the movements clearly, a cord has been laid down with another crossing it at right angles. My opponent stands with his toe-tips just touching the cord, the feet perhaps a little wider than shoulder-width. I was standing facing him in the same position, and now, in Fig. 1, I make the first move.

First Movement. I step on to the cross with my right foot. Make the step with the toes; if the foot comes flat on the mats, the large area will increase friction and I shall not be able to turn smoothly later on.

Читать дальше