When structuring a teaching unit on short films, one can resort to the well-known lesson planning patterns (Thaler 2012, 2007b):

PPP (presentation, practice, production)

PWP (pre-while-post)

GtD (global-to-detail)

TBLL (Task-based Language Learning)

Music Video Approach (3 codes, 7 combinations)

In order to focus on listening-viewing or / and cinematic analysis, the 10-step approach can be recommended (Thaler 2014, Fig. 10).

| Step |

Phase |

Content / Functions |

| 1 |

Lead-in |

Introducing the situation: who, what …Justifying the need to watch |

| 2 |

Prep work |

Key phrasesIntercultural background |

| 3 |

1st purpose |

Intention (global understanding)Tasks |

| 4 |

1st viewing |

Whole film |

| 5 |

Global comprehension |

Students’ answers |

| 6 |

2nd purpose |

Intention (detailed understanding)Tasks |

| 7 |

2nd viewing |

Film |

| 8 |

Detailed comprehension |

Students’ answers |

| 9 |

(optional: 3rd viewing) |

Focusing taskPart of filmDiscussion |

| 10 |

Wrap-up |

Follow-up activitiesAnalysisDiscussionTransfer |

Fig. 10: 10-step approach to listening-viewing

This 10-step approach can be exemplified with the hilarious black humour skit Fatal Beatings ( www.youtube.com/watch?v=fZMoB6ms2mE), in which a meeting between a strict headmaster (Rowan Atkinson) and a worried student’s father rapidly goes downhill after the headmaster mentions casually that he has beaten his son to death (Fig. 11).

| Step |

Phase |

Content |

| 1 |

Lead-in |

T activates background information on Rowan Atkinson / Mr Bean. |

| 2 |

Prep work |

The communicative situation of the clip is introduced: who, where, what.A few key phrases may be pre-taught. |

| 3 |

1st purpose |

T announces that the presentation of the film will be stopped three times in order to elicit feedback from the S. |

| 4 |

1st viewing |

The whole film is shown, the pause button is pressed at the following points, and S have to guess:0:29 (»Tommy is in trouble«): what trouble?0:52 (»If he wasn’t dead, I’d have him expelled«): why dead?3:46 (»I’ve been pulling your leg«): what punchline? |

| 5 |

Global comprehension |

With each freeze frame, answers from the S are collected. |

| 6 |

2nd purpose |

S are asked to focus on the different sources of humour during the second viewing of this skit. |

| 7 |

2nd viewing |

The video is presented straight through. |

| 8 |

Detailed comprehension |

S answers on humour are discussed. |

| 9 |

3rd viewing |

A subtitled version of the video with several spelling and lexical mistakes is shown, and S are asked to shout »Stop!« whenever they identify a mistake. The correct versions are written on the board. |

| 10 |

Wrap-up |

The appropriateness of this video concerning its content and the role of black humour are discussed. |

Fig. 11: Fatal Beatings

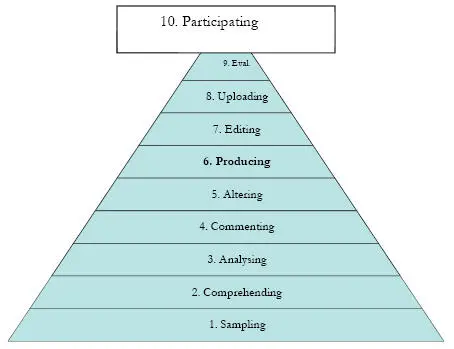

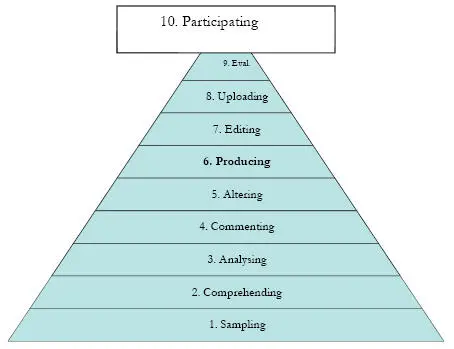

While this 10-step model is intended to foster the first two skills of short film literacy (see Fig. 8), promoting the third skill, i.e. creating, can be guided by the 10-level pyramid, in which the autonomous production of a short film by the learners takes centre stage (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: Ten – Level Pyramid

When employing short films in TEFL, teachers should resort to Balanced Teaching , i.e. a synthesis of closed and open methods (Thaler 2008). Fig. 13 elucidates how this basic approach can be adapted for short films.

| Balanced Teaching |

| Closed Teaching |

& |

Open Learning |

| teacher-frontedcinematic analysisclosed exercisesone filmdeskbound approach |

student-centredlistening-viewing for gistopen tasksintermedialityindependent study |

| motivating & effectiveTEFL |

Fig. 13: Balanced Teaching with short films

Donaghy, Kieran (2015). Film in Action. Peaslake: Delta Publishing.

Heinrich, Katrin (1997). Der Kurzfilm. Geschichte, Gattungen, Narrativik. Alfeld: Coppi.

Keddie, Jamie (2014). Bringing Online Video into the Classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

KMK (Hg.) (2003). Bildungsstandards mittlerer Schulabschluss. www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2003/2003_12_04-BS-erste-Fremdsprache.pdf

KMK (Hg.) (2012). Bildungsstandards allgemeine Hochschulreife. www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2012/2012_10_18-Bildungsstandards-Fortgef-FS-Abi.pdf

Monaco, James (2009). How to Read a Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stempleski, Susan/Tomalin, Barry (2001). Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thaler, Engelbert (2016). Kurzfilme im Fremdsprachenunterricht. Praxis Fremdsprachenunterricht 6, 7–11.

Thaler, Engelbert (2015). Literal Music Videos. Praxis Fremdsprachenunterricht 3, 6–7.

Thaler, Engelbert (2014). Teaching English with Films. Paderborn: UTB.

Thaler, Engelbert (2012). Englisch unterrichten. Berlin: Cornelsen.

Thaler, Engelbert (2008). Offene Lernarrangements im Englischunterricht. Berlin: Langenscheidt.

Thaler, Engelbert (2007a). Film-based Language Learning. Praxis Fremdsprachenunterricht 1, 9–14.

Thaler, Engelbert (2007b). Schulung des Hör-Seh-Verstehens. Praxis Fremdsprachenunterricht 4, 12–17.

Thaler, Engelbert (2000). Monty Python. Paderborn: Schöningh.

Goose Bumps – How the Language of Film Enters into Language Teaching with Films

Klaus Maiwald

Part 1 of the following article outlines didactic reasons and directions of working with films and short films. Part 2 will take a closer look at the innertextual and intertextual qualities of a particular short film, showing how the language of film, its formal means and aesthetic techniques, is integral to language learning with film. Part 3 concludes that while film analysis is no end in itself, it is required in defining and fulfilling language oriented tasks.

1 Didactic Reasons and Directions of Working with (Short) Films

Why work with (short) films in language teaching? A simple answer to that question is: because they exist. We study music; we study painting; we study architecture; we study literature; so we study film. (We might even consider film a form of literature.) In any case, film is an art form with a history spanning well over a hundred years (see Faulstich 2005). Film has developed genuine aesthetic codes, for example cut and montage, and specific genres, for example the Western, the Road Movie, the Thriller (see Hickethier 2007: 201ff.; Kammerer 2009). And film has brought forth renowned auteurs and œuvres – or slightly less pretentious: film makers and works. Think about Sergei Eisenstein, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Woody Allen, to name but a few. In his voluminous yet highly readable study The Big Screen. The Story of the Movies and What They Did to Us , David Thomson (2012) traces more than a century in which films have been shaping our thoughts and feelings, about the world and ourselves. If one purpose of higher education is to open up legitimate cultural objects and processes, there is no way around film – unless we exclude film from an elitist concept of a supposed »high culture«.

Читать дальше