Self-concept has a hierarchical, multidimensional structure, which becomes increasingly differentiated with age. Inspired by William James’ earliest works on psychology from the 19th century, the hierarchical structure model of self-concept has dominated research until today. Of particular interest for my research project is the academic strand of Shavelson et al.’s version of this model (1976), which not only depicts the hierarchical order of self-concept facets (with the general self-concept at the apex resembling a core or relatively stable part), but also its multidimensionality (e.g. self-concept across different academic domains). Within the verbal academic dimension of self-concept (including foreign language learning), for example, Mercer (2011a) approached depicting different foreign language self-concepts in a three dimensional model. Unlike the hierarchical model, this sphere model is able to capture the contextual and dynamic nature of and, more importantly, between different foreign language self-concepts.

Self-concept has a relatively stable core and more dynamic peripheral parts. In what ways is self-concept dynamic and contextual? Markus and Wurf’s model (1987) takes up the symbolic interactionist’s notion that forming one’s self-concept is a social process. It also takes into account that how we ourselves perceive our actions and appraisals shapes our self-concept. Both inter- and intra-personal factors affect how our working self-concept either internalizes or discards incoming, potentially self-relevant, information. In the case of the young-old language learners, how they perceive their own language learning process and progress (intra-personal factors), as well as how they ‘filter’ incoming self-relevant information from the teacher, other language learners in their class, and people they communicate with in the target language outside the classroom (inter-personal factors), form the basis of their language learning self-concept. Markus and Wurf’s model shows how self-concept can be stable and dynamic at the same time. Finally, what we need to keep in mind is that self-concept formation is a bi-directional process between our real and idealized self. A young-old language learner’s self-concept grows out of the tension of his or her perceived status quo and his or her envisioned ideal language learner self, guiding his or her further language learning process.

Self-concept differs from other self-related constructs in the degree of cognition, evaluation, and specificity involved in its development and measurement. It is not always easy to keep clear-cut boundaries between the commonly addressed concepts in SLA research such as self-concept, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-confidence when trying to measure or to investigate them. Contrasting them makes boundaries and overlaps visible. On a scale ranging from highly evaluative to highly cognitive, self-esteem is more on the evaluative side than self-concept, which is more cognitive in nature. Self-efficacy is even further down on the cognitive side of the scale compared to self-concept. What remains somewhat open to debate and difficult to differentiate when measuring is the degree of task-specificity of self-concept vs. self-efficacy, with the latter being considered the more task-specific one. Self-confidence, another often investigated psychological concept in SLA-research, differs from self-concept in that it is more strongly connected to anxiety and has its roots mainly in contact experiences with the L2 (direct and indirect). Thus, in many cases a single item or a group of items in the questionnaire for this study as well as an interview question can indeed point to several self-aspects of a young-old language learner. For instance, asking a young-old learner to rate her English skills on a scale from 1 to 10 together with an elaboration of the rating, can help to draw conclusions not only about her self-concept but also about, for example, her self-esteem.

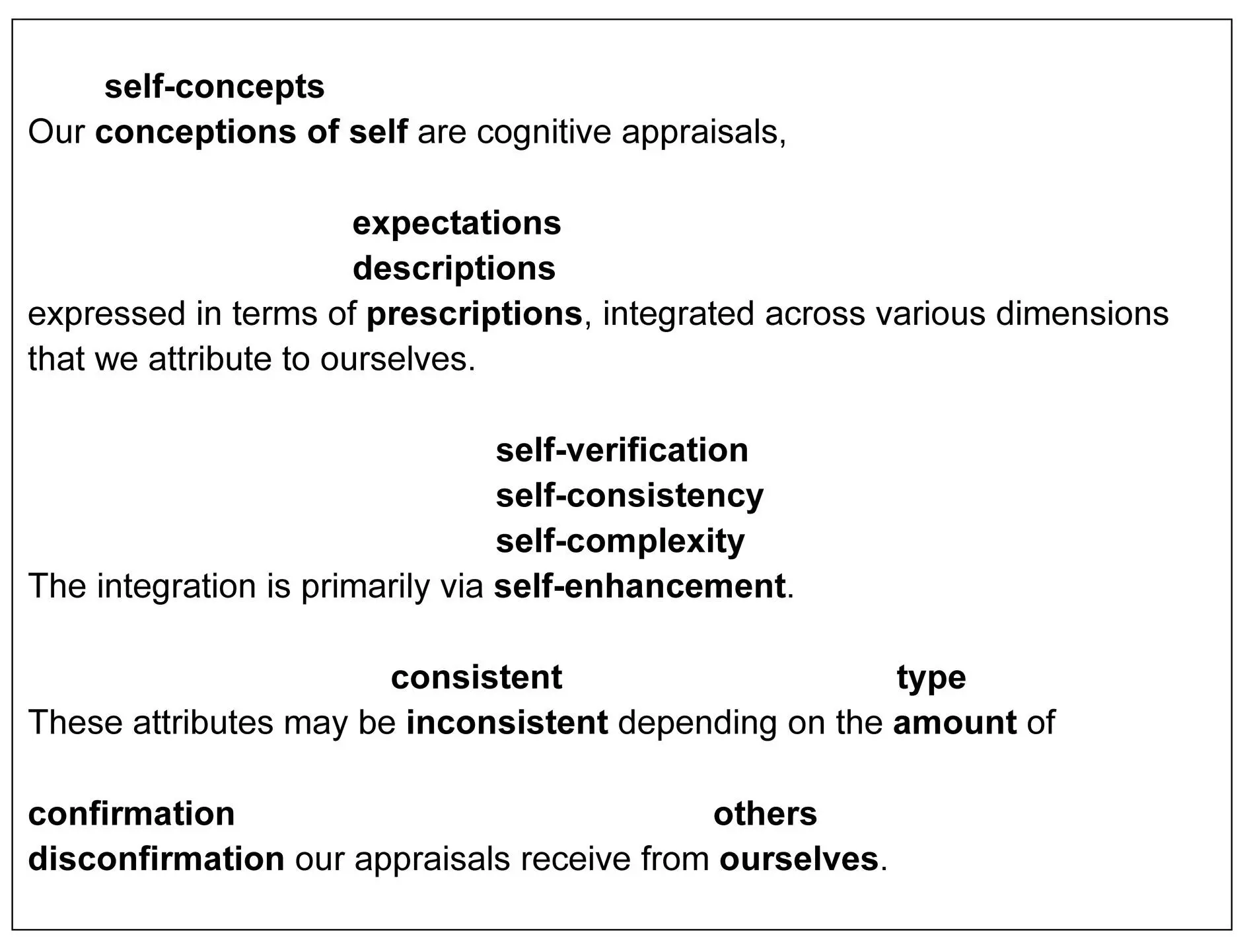

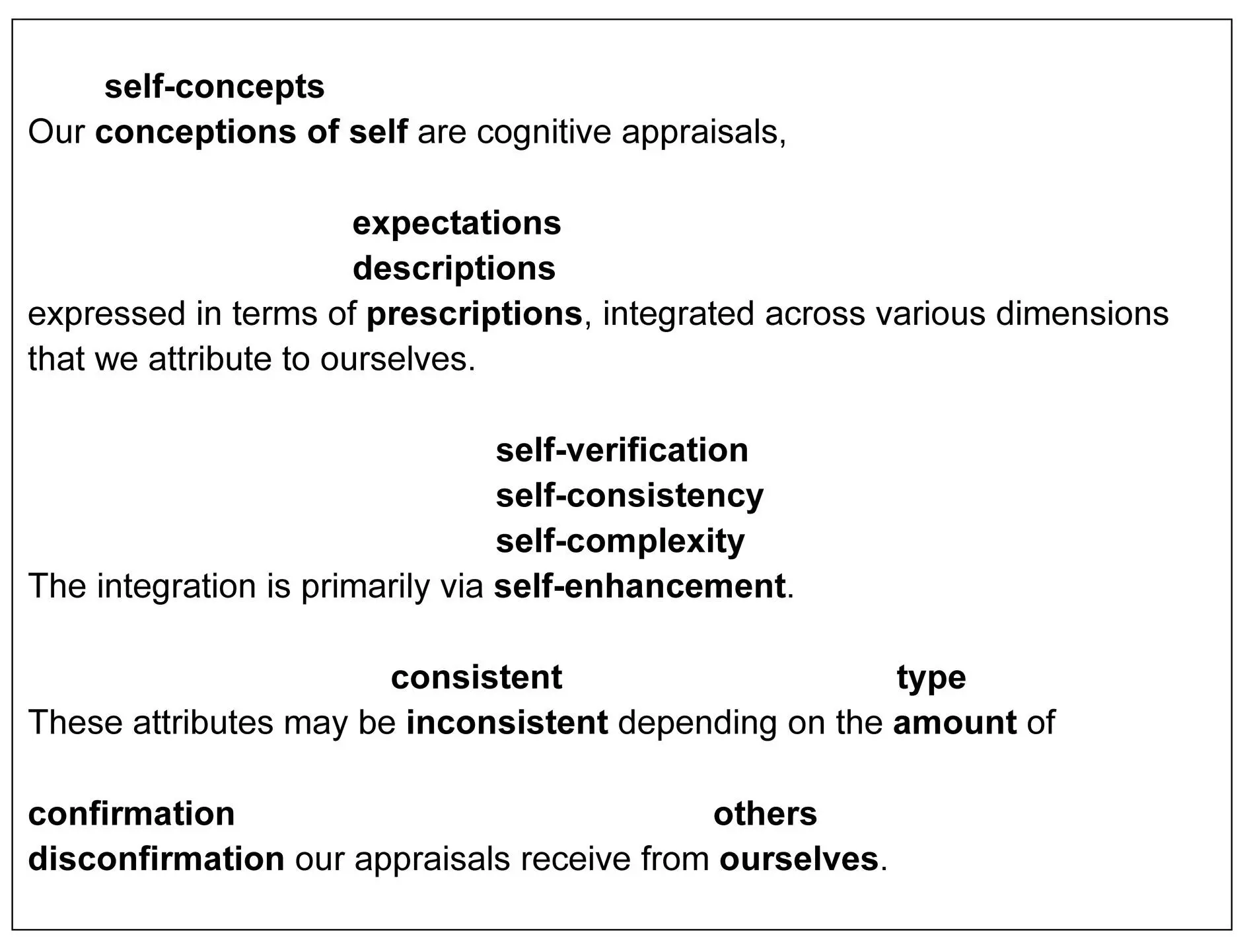

Finally, to illustrate all of the central characteristics of self-concept that I have discussed above in a more condensed way, I would like to draw on Hattie’s (1992) facet analysis of self-concept (see figure 3.1). While he uses the term cognitive appraisals to describe self-concepts (alongside expectations, descriptions, and prescriptions), I have used the terms beliefs and perceptions. The integration across various dimensions and the ways in which this happens (self-verification etc.) corresponds with the multidimensional, hierarchical structure (self-concept structure) and the internalization process (self-concept formation) discussed in sections 3.2.2 and 3.2.3. The last part of his facet analysis refers to the stability vs. dynamics of self-concept (the core and peripheral parts of self-concept discussed in section 3.2.3) as well as how we use intra- and inter-personal information ( dis-/confirmation ) to (re-)shape our self-concept.

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

Facet analysis of self-concept by Hattie (1992: 37 – bold by me)

Arriving at an overall understanding of what constitutes self-concept and how it is formed, I would like to focus on a more specific area of self-concept in the next section: its temporal facets. As mentioned above, the dynamic between actual and ideal self is a driving force in a young-old learner’s language learning process. What roles do the past, present, and future selves have on young-old language learners? What can we learn from investigating their possible, ideal, and ought-to selves in order to find out how to facilitate their language learning process? Second language acquisition research has already focused on the temporal aspects of self-concept and possible selves, resulting in different models that help to understand the language learner self from a temporal and motivational perspective (see section 3.4). The next section on the temporal self presents and discusses the foundation for SLA models of language learning and the self.

What’s past is prologue.

- Shakespeare, The Tempest , act II, scene I, lines 253-54 -

Mercer and Williams (2014), in their concluding remarks, divide research on the self in the SLA classroom into two broad categories: the contextual self and the temporal self.1 Based on this distinction I would like to focus on the latter – the temporal – aspect of self-concept in this section. This is not to say that context or the contextual self do not play a role in my study, as we will see in the next chapter. I focus on the temporal aspect for two main reasons:

Firstly, as we will see in this and the following section, the temporal perspective on the self in psychology and SLA research lays the foundation for central theories and models used to explore the self. In SLA research, for example, Dörnyei ’s (2005) L2 Motivational Self System (L2MSS) draws on future-oriented self-aspects such as ideal and ought-to selves of L2 language learners (see section 3.4.1).

Secondly, for no other younger age group does time play such a central role as for the young-old (Carstensen 2006; Koutoukidis et al. 2013: 234; Russell 2011). They can look back onto a longer past than younger age groups, with various experiences to feed their current perception of self and construct future-oriented selves. Simultaneously, this particular phase of life is connected to major life changes, such as retirement, children having moved out from home (‘empty-nest syndrome’), or higher death rates among friends of their age, which trigger an increased awareness of time and the limits of life.

Читать дальше

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1