1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...17 17 17. Alice O’Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century US History (2001), ch. 9. This book is a must-read for any serious student of poverty in America, whatever their discipline.

18 18. W.E.B. Du Bois, On Sociology and the Black Community (1978), p. 37. This expression refers to caricatural knowledge of African American society and culture produced by white scholars in the Jim-Crow south, based on distant and circumstantial observation (such as can be carried out while riding a Pullman car on a vacation trip).

19 19. Loïc Wacquant, “A Janus-Faced Institution of Ethnoracial Closure: A Sociological Specification of the Ghetto” (2012a).

20 20. A fuller account of my biographical and intellectual pathway into and inside the South Side is Loïc Wacquant, “The Body, the Ghetto and the Penal State” (2009a).

21 21. Loïc Wacquant, Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer (2004 [2000], exp. anniversary ed. 2022).

22 22. William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (1996).

23 23. Morton Gabriel White and Lucia White, The Intellectual Versus the City: From Thomas Jefferson to Frank Lloyd Wright (1962); Andrew Lees, Cities Perceived: Urban Society in European and American Thought, 1820–1840 (1985); Steven Conn, Americans Against the City: Anti-Urbanism in the Twentieth Century (2013), ch. 1.

24 24. Robert A. Beauregard, Voices of Decline: The Postwar Fate of US Cities (1993).

25 25. White and White, The Intellectual Versus the City.

26 26. Paul S. Boyer, Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920 (1978), p. 57.

27 27. David Ward, Poverty, Ethnicity, and the American City, 1840–1925: Changing Conceptions of the Slum and the Ghetto (1989), pp. 53–61.

28 28. Christian Topalov, “The City as Terra Incognita: Charles Booth’s Poverty Survey and the People of London, 1886–1891” (1993 [1991]).

29 29. Boyer, Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920, p. 126.

30 30. Boyer, Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920, p. 153. The practice is a precursor to the public systematization and private diffusion of criminal records in the late twentieth century as dissected by James B. Jacobs, The Eternal Criminal Record (2015).

31 31. Boyer, Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920, p. 176.

32 32. Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (1988). This is in sharp contrast to the bourgeoisie of continental Europe, which viewed the city as the fount of civilization and civility and aspired to reside at its historic center.

33 33. Robert M. Fogelson, Bourgeois Nightmares: Suburbia, 1870–1930 (2007), part 2.

34 34. Reinhart Koselleck, “The Historical-Political Semantics of Asymmetric Counterconcepts.” (2004).

35 35. Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America (1996), p. 166.

36 36. Boyer, Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920, pp. 200, 222–32.

37 37. Thomas Lee Philpott, The Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood Deterioration and Middle-Class Reform (1978), p. x.

38 38. Philpott, The Slum and the Ghetto, pp. 346–7; Spear, Black Chicago, pp. 169–79; Drake and Cayton, Black Metropolis, ch. 8.

39 39. William M. Tuttle, Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 (1970); Lee E. Williams, Anatomy of Four Race Riots: Racial Conflict in Knoxville, Elaine (Arkansas), Tulsa, and Chicago, 1919–1921 (2008). See also Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot (1923), one of the most remarkable accounts of the nexus of race, class, and space ever written (largely by sociologist Charles S. Johnson).

40 40. Conn, Americans Against the City, ch. 3.

41 41. Conn, Americans Against the City, pp. 94–5.

42 42. Peter Hall, Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880, 4th ed. (2014), ch. 4.

43 43. Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (1987), chs. 11 and 12; Jon C. Teaford, The Rough Road to Renaissance: Urban Revitalization in America, 1940–1985 (1990).

44 44. Beauregard, Voices of Decline, p. 137.

45 45. Peter B. Levy, The Great Uprising: Race Riots in Urban America during the 1960s (2018).

46 46. Cited in Thomas Byrne Edsall and Mary D. Edsall, Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights, and Taxes on American Politics (1991), p. 52.

47 47. Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (2008), pp. 334–51; William L. Van Deburg, New Day in Babylon: The Black Power Movement and American Culture, 1965–1975 (1992).

48 48. Wacquant, “A Janus-Faced Institution of Ethnoracial Closure,” pp. 10–12.

49 49. Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (1968); Robert M. Fogelson, “White on Black: A Critique of the McCone Commission Report on the Los Angeles Riot.” (1967), pp. 363–4. Read the condemnation of the “separatist charade” as “a carbon copy of white supremacy” and a “Lorelei of black racism” by Kenneth B. Clark, “The Black Plight, Race or Class?” (1980).

50 50. Beauregard, Voices of Decline, pp. 185–216. A flood of scholarly and journalistic books with the words “urban crisis” in their title gushed out in the 1960s and 1970s.

51 51. Lillian B. Rubin, Quiet Rage: Bernie Goetz in a Time of Madness (1986); Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, ch. 11; Michael Tonry, Malign Neglect: Race, Crime and Punishment in America (1995); Loïc Wacquant, Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity (2009b), chs. 2–3 and 7.

52 52. Robert Gooding-Williams (ed.)., Reading Rodney King, Reading Urban Uprising (2013).

53 53. For an analysis of how rappers both play on and amplify the imagery of anti-urbanism as anti-blackness, see Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (1994), ch. 4.

PART ONE THE TALE OF THE “UNDERCLASS”

“Nothing is so firmly believed as that which we least know.” Michel de Montaigne, Essais , 1580

“The tendency has always been strong to believe that whatever received a name must be an entity or being, having an independent existence of its own. And if no real entity answering to the name could be found, men did not for that reason suppose that none existed, but imagined that it was something particularly abstruse and mysterious.”

John Stuart Mill, Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind , 1829

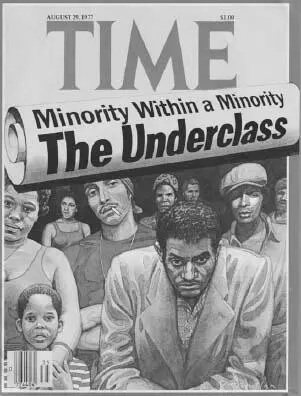

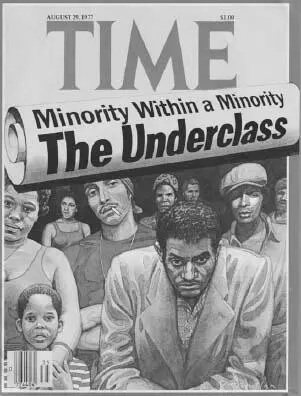

A new social animal burst upon the American urban landscape at the close of the 1970s and soon sowed fear and loathing among the citizenry as well as caused spiking worry among public officials. Its discovery triggered a veritable media tsunami: major national outlets devoted lurid articles, fulminating editorials and alarming reports on the noxious and predatory behaviors alleged to characterize it. Politicians of every stripe rushed to denounce its sinister presence at the heart of the metropolis, in which they detected now the symptom, now the cause of the unraveling of the derelict districts that disfigured the nation’s major cities. Social scientists and public policy experts were summoned to establish its geographic location, to specify its social habitat, to enumerate its ranks, and to elucidate its mores, so that the means by which to contain its malignant proliferation might be urgently devised. Legislative hearings were held, academic conferences organized, and scholarly tomes and popular accounts proliferated apace. 1

Читать дальше