Andrew H. Cobb - Herbicides and Plant Physiology

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrew H. Cobb - Herbicides and Plant Physiology» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Herbicides and Plant Physiology

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Herbicides and Plant Physiology: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Herbicides and Plant Physiology»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Discover the latest developments in herbicide and weed biology Herbicides and Plant Physiology,

Arabidopsis

Herbicides and Plant Physiology

Herbicides and Plant Physiology — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Herbicides and Plant Physiology», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

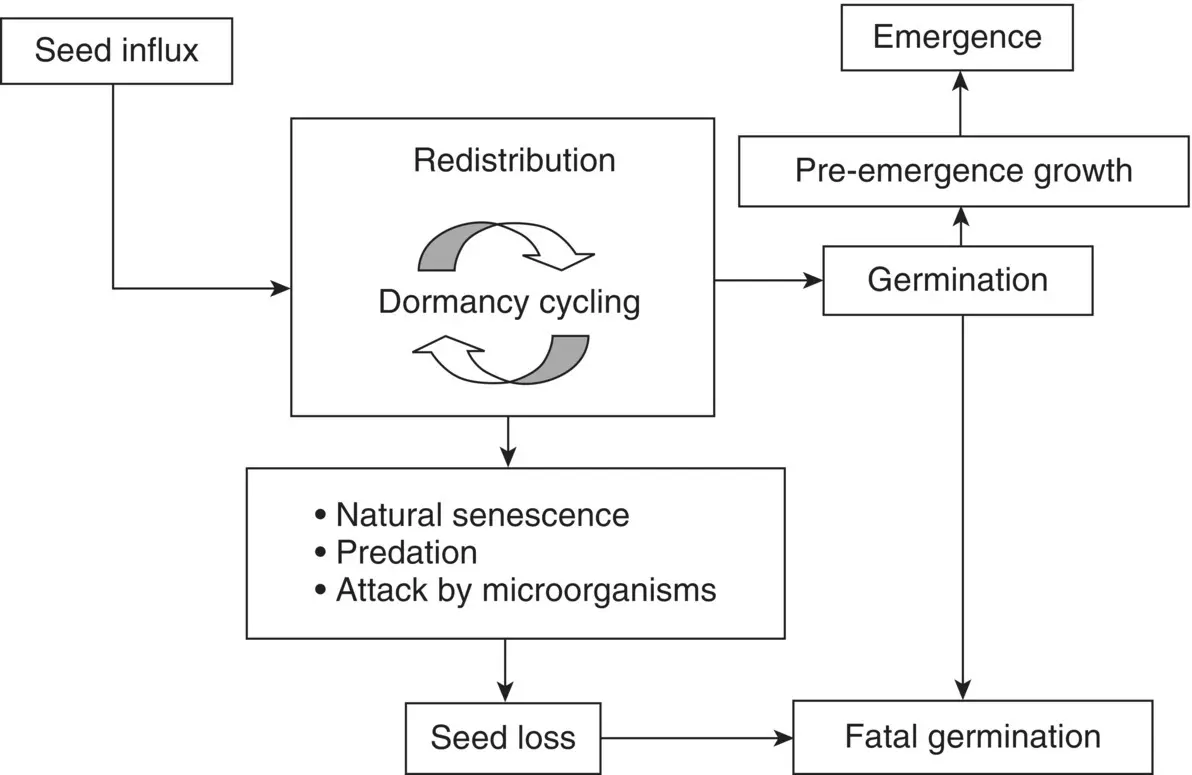

Source: Liebman, M., Mohler, C.L. and Staver, C.P. (2001) Ecological Management of Agricultural Weeds . Cambridge University Press. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

1.5.7 Dormancy and duration of viability

Although the seed production figures of an individual plant are impressive ( Table 1.9), the total seed population in a given area is of greater significance. The soil seed reservoir reflects both past and present seed production, in addition to those imported from elsewhere, and is reduced by germination, senescence and the activity of herbivores ( Figure 1.3). Estimates of up to 100,000 viable seeds per square metre of arable soil represent a massive competition potential to both existing and succeeding crops, especially since the seed rate for spring barley, for instance, is only approximately 400 m −2! Under long term grassland, weed seed numbers in soil are in the region of 15,000–20,000 m −2, so conversion of arable land to long‐term grassland offers growers a means of reducing soil weed‐seed burden.

The length of time that seeds of individual species of weed remain viable in soil varies considerably. The nature of the research involved in collecting such data means that few comprehensive studies have been carried out, but those that have (see Toole and Brown, 1946, for a 39 year study!) show that although seeds of many species are viable for less than a decade, some species can survive for in excess of 80 years (examples include poppy and fat hen). Evidence from soils collected during archaeological excavations reveals seeds of certain species germinating after burial for 100–600 (and maybe even up to 1700!) years (Ødum, 1965).

Dormancy in weed seeds allows for germination to be delayed until conditions are favourable. This dormancy may be innate and contributes to the periodicity of germination, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. In addition, dormancy may be induced or enforced in non‐dormant seeds if environmental conditions are unfavourable. This ensures that the weed seed germinates when conditions are most conducive to seedling survival.

Figure 1.3 Factors affecting the soil seed population.

Source: Grundy, A.C. and Jones, N.E. (2002) What is the weed seed bank? In: Naylor, R.E.L. (ed.) Weed Management Handbook , 9th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing/BCPC. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

1.5.8 Plasticity of weed growth

The ability of a weed species to make rapid phenotypic adjustment to environmental change (acclimation) may offer a considerable strategic advantage to the weed in an arable context. An example of the consequence of such plasticity is environmental sensing by fat hen ( Chenopodium album ). This important weed can respond to canopy shade by undergoing rapid stem (internode) elongation, although the plant is invariably shorter if growing in full sun. Similarly, many species can undergo sun–shade leaf transitions for maximum light interception (Patterson, 1985).

1.5.9 Photosynthetic pathways

Photosynthesis, the process by which plants are able to convert solar energy into chemical energy, is adapted for plant growth in almost every environment on Earth. For most weeds and crops photosynthetic carbon reduction follows either the C 3or the C 4pathway, depending on the choice of primary carboxylating enzyme. In C 3plants this is ribulose 1,5‐bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCo) and the first stable product of carbon reduction is the three‐carbon acid, 3‐phosphoglycerate. Alternatively, in C 4plants the primary carboxylator is phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) and the initial detectable products are the four‐carbon acids, oxaloacetate, malate and aspartate. These acids are transferred from the leaf mesophyll cells to the adjacent bundle sheath cells where they are decarboxylated and the CO 2so generated is recaptured by RuBisCo. Since PEPC is a far more efficient carboxylator than RuBisCo, it serves to trap CO 2from low ambient concentrations (micromolar in air) and to provide an effectively high CO 2concentration (millimolar) in the vicinity of the less efficient carboxylase, RuBisCo. In this way, C 4plants can reduce CO 2at higher rates and are often perceived as being more efficient than C 3plants. In addition, because of their more effective reduction of CO 2, they can operate at much lower CO 2concentrations, such that stomatal apertures may be reduced and so water is conserved.

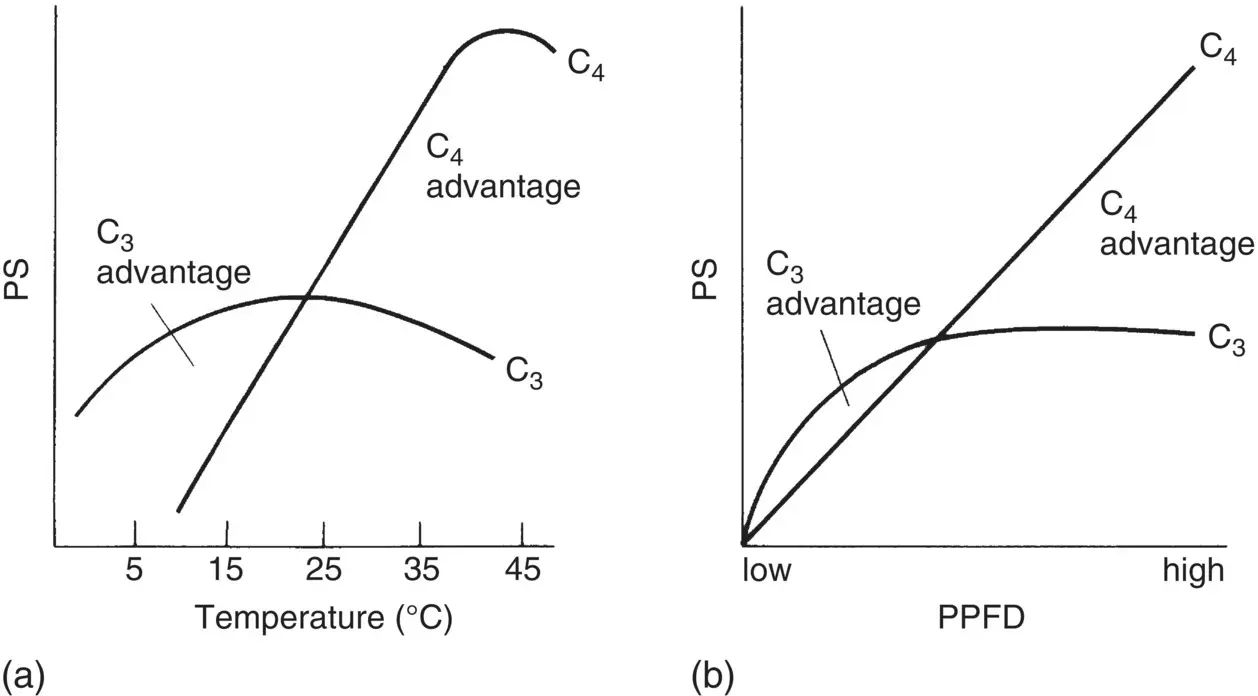

The C 4pathway is often regarded as an ‘optional extra’ to the C 3system, and offers a clear photosynthetic advantage under conditions of relatively high photon flux density, temperature and limited water availability, that is in tropical and mainly subtropical environments. Conversely, plants solely possessing the C 3pathway are more advantaged in relatively temperate conditions of lower temperatures and photon flux density, and an assumed less limiting water supply ( Figure 1.4).

Returning to the interaction between crop and weed, it is therefore apparent that, depending on climate, light to severe competition may be predicted. For example, a temperate C 3crop may not compete well with a C 4weed (e.g. sugar beet, Beta vulgaris , and redroot pigweed, Amaranthus retroflexus ) and a C 4crop might be predicted to outgrow some C 3weeds (e.g. maize, Zea mays , and fat hen, Chenopodium album ). Less competition is then predicted between C 3crop and C 3weeds in temperate conditions, with respect to photosynthesis alone.

In reality, C 4weeds are absent in the UK but widespread in continental, especially Mediterranean, Europe. In the cereal belt of North America, however, C 4weeds pose a considerable problem and it is notable that eight of the world’s top 10 worst weeds are C 4plants indigenous to warmer regions ( Table 1.10). It will be of both interest and commercial significance if the C 4weeds become more abundant in regions currently termed temperate (e.g. northern Europe), with the development of of climate change.

Of the 435,000 plant species on Earth, C 4photosynthesis is present in fewer than 2%, but accounts for about 25% of plant productivity. It is a carbon dioxide‐concentrating mechanism that evolved relatively recently, that makes photosynthesis more efficient. It is noteworthy that many major weeds are C 4plants ( Table 1.10). In the C4 Rice Project ( www.c4rice.com), gene editing is being used to introduce C4 genes into crops such as rice. Rice currently accounts for 19% of all calories consumed globally. If successful, GE rice could be 50% more productive than the current C3 rice.

Figure 1.4 Expected rates of photosynthesis (PS) by C 3and C 4plants at (a) varying temperature and (b) varying photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD).

Source: Andy Cobb, 1992.

Table 1.10 Photosynthetic pathway of the world’s 10 worst weeds.

Source: Holm, L.G., Plucknett, D.L., Pancho, J.V. and Herberger, J.B. (1977) The World’s Worst Weeds. Distribution and Biology . Hawaii: University Press.

| Latin name | Common name | Photosynthetic pathway | Number of countries where plant is known as a weed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 . Cyperus rotundus (L.) | Purple nutsedge | C 4 | 91 |

| 2 . Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Bermuda grass | C 4 | 90 |

| 3 . Echinochloa crus‐galli (L.) Beauv. | Barnyard grass | C 4 | 65 |

| 4. Echinochloa colonum (L.) Link. | Jungle rice | C 4 | 67 |

| 5 . Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. | Goose grass | C 4 | 64 |

| 6 . Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers. | Johnson grass | C 4 | 51 |

| 7 . Imperata cylindrica (L.) Beauv . | Cogon grass | C 4 | 49 |

| 8 . Eichornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms. | Water hyacinth | C 3 | 50 |

| 9. Portulaca oleracea (L.) | Purslane | C 4 | 78 |

| 10. Chenopodium album (L.) | Fat hen | C 3 | 58 |

1.5.10 Vegetative reproduction

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Herbicides and Plant Physiology»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Herbicides and Plant Physiology» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Herbicides and Plant Physiology» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.