Andrew H. Cobb - Herbicides and Plant Physiology

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrew H. Cobb - Herbicides and Plant Physiology» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Herbicides and Plant Physiology

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Herbicides and Plant Physiology: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Herbicides and Plant Physiology»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Discover the latest developments in herbicide and weed biology Herbicides and Plant Physiology,

Arabidopsis

Herbicides and Plant Physiology

Herbicides and Plant Physiology — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Herbicides and Plant Physiology», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Most non‐native plants in the UK were introduced by plant collectors in the last 200 years. They become invasive when they have negative impacts on native species, our economy and even our health. Alien plant species become a problem because they are growing in habitats away from their natural predators and so can spread with ease and do not need to invest valuable energy in biologically expensive chemical defence mechanisms. In addition, the Novel Weapons Hypothesis proposes that in some cases allelopathic chemicals produced by alien species are more effective against native species in invaded areas than they are against species from the alien’s natural habitat (Inderjit et al ., 2007). This gives further ecological advantage to some invasive species of plant.

The Royal Horticultural Society notes 1402 invasive plants in the UK, of which 108 can have negative effects, and its website offers advice and guidance on how they should be dealt with ( www.rhs.org.uk/advice/profile?PID=530). The EU Regulation on Invasive Alien Species lists 36 plants.

Observations of the pathogens and predators that affect these invasive plants in their natural habitats may identify mycoherbicides and other biological controls that may prove useful in their management. Research into such controls for Japanese Knotweed ( Fallopia japonica ), Himalayan Balsam ( Impatiens glandulifera ) and Giant Hogweed ( Heracleum mantegazzianum ) have so far produced, at best, limited success (Tanner, 2008).

Moles et al . (2008) have recently proposed a framework for predicting plant species which may present a risk of becoming invasive weeds. This may prove more useful than Table 1.8in risk assessment relating to alien species, prior to their becoming major weed problems.

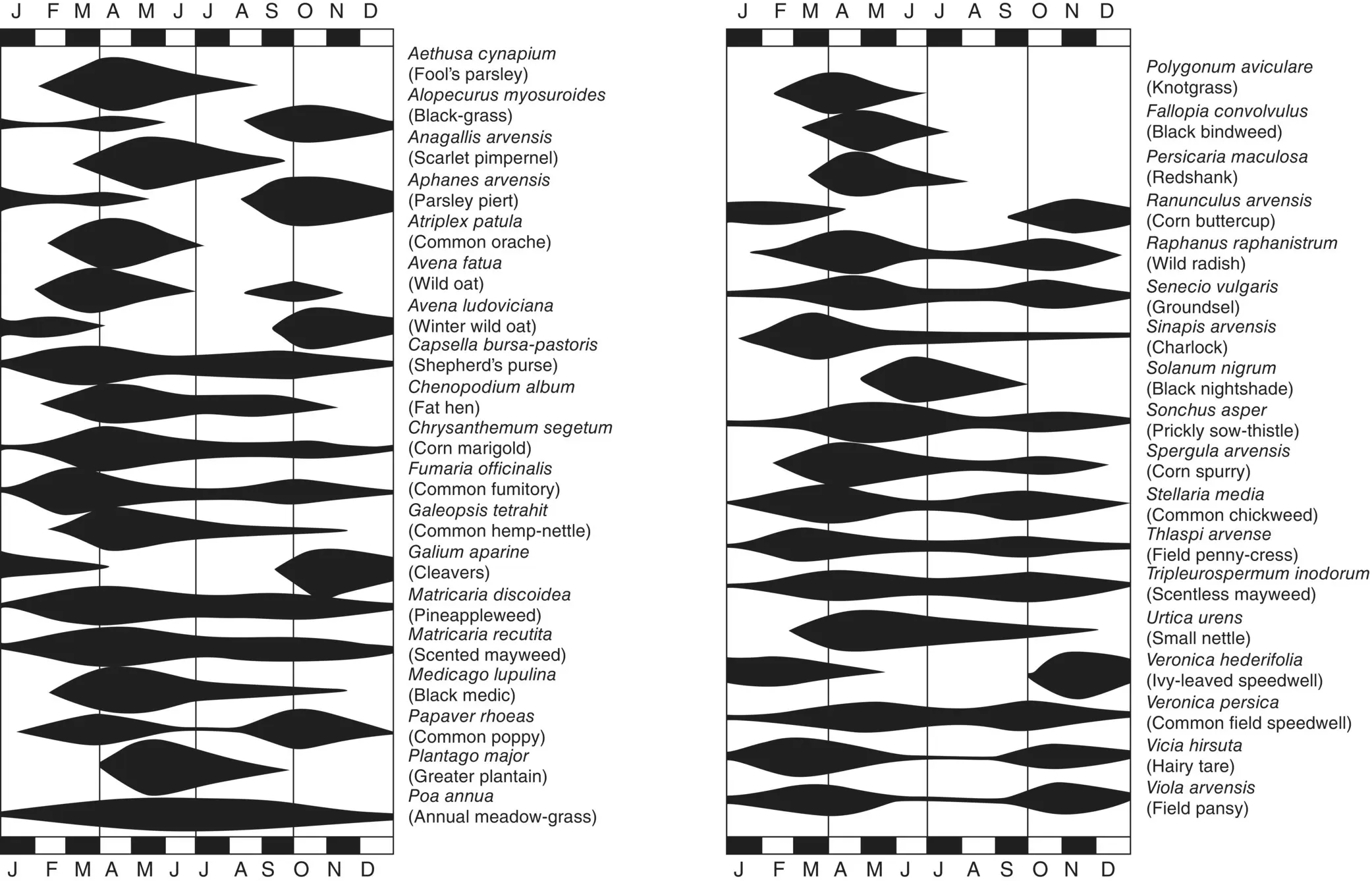

1.5.2 Germination time

The success of some weeds is due to close similarity with a crop. If both the weed and the crop have evolved with the same agronomic or environmental conditions they may share identical life cycles and life styles. Thus, if weed seed maturation coincides with the crop harvest, the chances of weed seed spread are increased. This phenomenon is often apparent in the grasses, such as barnyard grass ( Echinochloa crus‐galli ) in rice, and wild oat ( Avena spp.) in cereals. In Europe, spring wild oats ( A. fatua ) germinate mainly between March and May, and the winter wild oat ( Avena ludoviciana ) shows maximum germination in November. Hence, the date of cereal sowing in relation to wild oat emergence is crucial to weed control. In general, weeds may be considered to occupy one of three categories: autumn germinators, spring germinators and those that germinate throughout the year. Figure 1.1illustrates the germination patterns for a number of common arable weeds. Autumn‐sown crops are more at risk from weeds that germinate during the autumn, when the crop is relatively small and uncompetitive. Conversely, weeds that cause problems in spring crops tend to be spring germinators (including the troublesome polygonums). Knowledge of the germination patterns of weeds plays a very important role in the designing of specific weed management strategies that will disrupt conditions conducive to the survival of the weed.

Further major problems are evident in sorghum, radish and sugar beet crops. Hybridisation of cultivated Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench with the weed S. halepense (L.) Pers. results in an aggressive perennial weed that produces few seeds, but demonstrates vigorous vegetative growth. Similarly, hybridisation between the radish ( Raphanus sativus L.) and the weed R. raphanistrum (L.) has produced a weedy form of R. sativus with dormant seeds and a root system that is more branched and penetrating than the crop. Lastly, hybridisation of sugar beet ( Beta vulgaris (L.) subsp. maritima ) has created an annual weed‐beet that sets seed, but fails to produce the typically large storage root. In each of these examples of crop mimicry by weeds, chemical weed control is extremely difficult owing to the morphological and physiological similarities between the weed and the crop.

1.5.3 Germination depth

Most arable weeds germinate in the top 5 cm of soil and this is the region that soil‐acting (residual) herbicides aim to protect. Where minimum cultivation or direct drilling is carried out, the aim is to avoid disruption of this top region of soil in an attempt to minimise weed‐seed germination. A small number weed species can germinate from greater depths and this may be due to these species possessing larger seed. A good example of this is wild oat ( Avena spp.), which can successfully germinate and establish from depths as low as 25 cm.

Figure 1.1 Germination periods of some common annual weeds. A greater width of the bar reflects greater germination.

Source: Hance, R.J. and Holly, K. (1990) Weed Control Handbook: Principles , 8th edn. Oxford: Blackwell. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

1.5.4 Method of pollination

The survival and growth of weed populations are dependent upon successful pollination. Weed species tend to rely on non‐specific insect pollinators (e.g. dandelion) or are wind pollinated (e.g. grasses), so their survival is not dependent on the size of population of specific insect pollinators. Annual weeds are predominantly self‐pollinated and, when outcrossing does take place, pollination is achieved by wind or insects. This means that a single immigrant plant may lead to a large population of individuals, each as well adapted as the founder and successful in a given site. Occasional outcrossing will alter the genotype, which may aid the occupation of a new or changing niche. Furthermore, many weeds, unlike crops, begin producing seed while the plants are small and young, and continue to do so throughout the growth season. In this way the weed density and spectrum in an arable soil may change quickly.

1.5.5 Seed numbers

Seeds are central to the success of weeds. As with all plants, weed seeds have two functions: the dispersal of the species to colonise new habitats, and the protection of the species against unfavourable environmental conditions via dormancy. Weeds commonly produce vast numbers of seeds, which may ensure a considerable advantage in a competitive environment, especially since the average number of seeds produced by a wheat plant is only in the region of 90–100 ( Table 1.9).

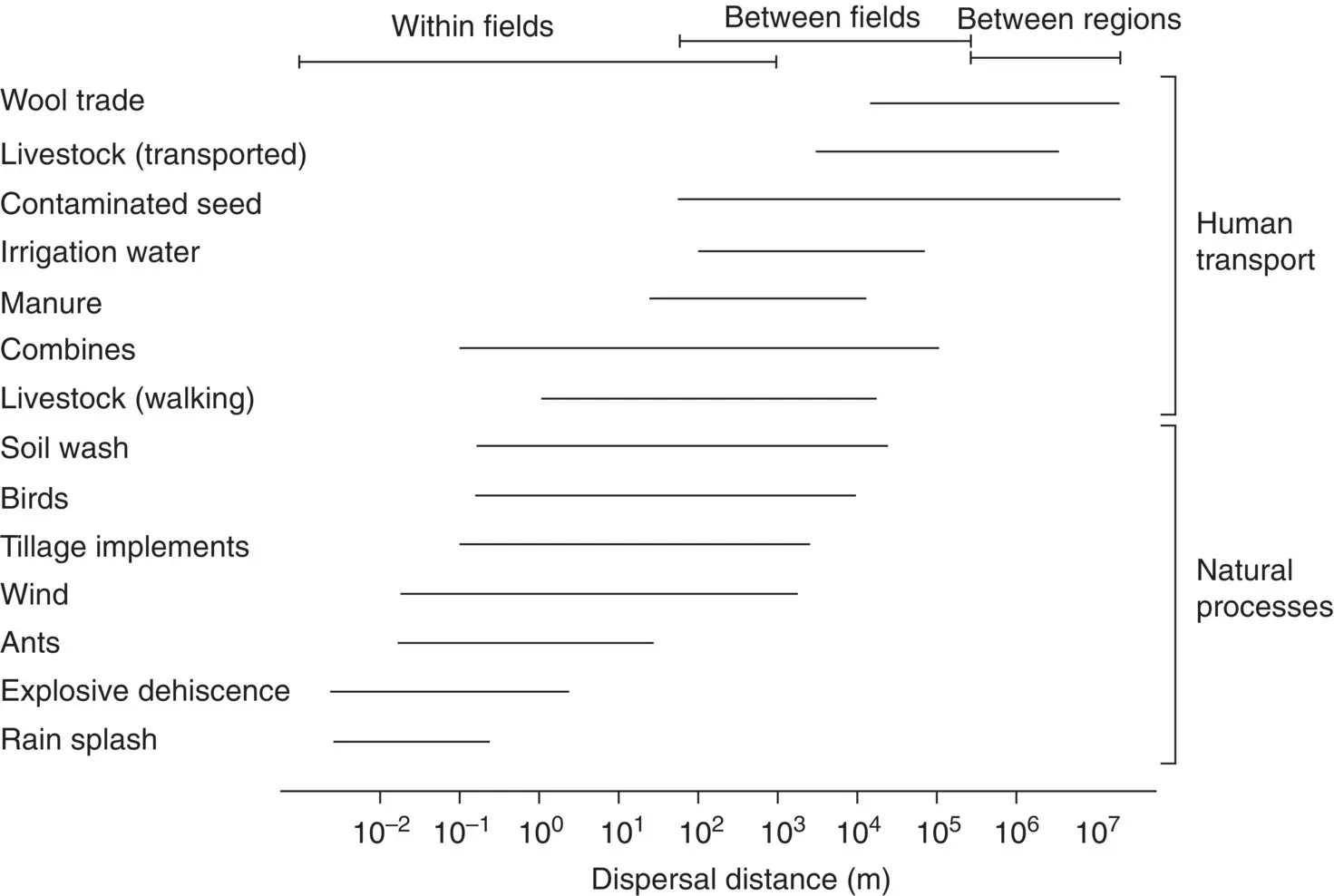

1.5.6 Seed dispersal

Many weed species possess methods of both short‐ and long‐distance seed dispersal ( Figure 1.2). By recognising these, it is possible to reduce the spread of weed seeds, a vital component of any integrated weed management strategy.

Table 1.9 Seed production by a number of common arable weeds and wheat.

Source: Adapted from Radosevich, S.R. and Holt, J.S. (1984) Weed Ecology: Implications for Vegetation Management . New York: Wiley; containing information from Hanf (1983).

| Weed | Common name | Seed production per plant |

|---|---|---|

| Veronica persica | Common field speedwell | 50–100 |

| Avena fatua | Wild oat | 100–450 |

| Galium aparine | Cleavers | 300–400 |

| Senecio vulgaris | Groundsel | 1100–1200 |

| Capsella bursa‐pastoris | Shepherd’s purse | 3500–4000 |

| Cirsium arvense | Creeping thistle | 4000–5000 |

| Taraxacum officinale | Dandelion | 5000 (200 per head) |

| Portulaca oleracea | Purslane | 10,000 |

| Stellaria media | Chickweed | 15,000 |

| Papaver rhoeas | Poppy | 14,000–19,500 |

| Tripleurospermum maritimum spp. inodorum | Scentless mayweed | 15,000–19,000 |

| Echinochloa crus‐galli | Barnyard grass | 2000–40,000 |

| Chamaenerion angustifolium | Rosebay willowherb | 80,000 |

| Eleusine indica | Goose grass | 50,000–135,000 |

| Digitaria sanguinalis | Large crabgrass | 2000–150,000 |

| Chenopodium album | Fat hen | 13,000–500,000 |

| Triticum aestivum | Wheat | 90–100 |

Figure 1.2 Some methods of weed seed dispersal with their estimated range in metres.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Herbicides and Plant Physiology»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Herbicides and Plant Physiology» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Herbicides and Plant Physiology» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.