While this is not a contraindication of fentanyl, it is important to remember that older patients often clear medications much more slowly than younger patients, and dosing may need to be adjusted to account for this, to avoid adverse effects.

Medications can come in varying concentrations and formulations for different modes of delivery. Adrenaline is a naturally occurring catecholamine hormone produced by the adrenal glands and is often also administered in the management of life‐threatening presentations such as cardiac arrest, anaphylaxis and croup.

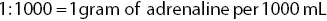

The concentration of adrenaline can be expressed as 1:1000 or 1:10 000. This is expressed verbally as ‘one in one thousand’ and ‘one in ten thousand’ respectively. This ratio refers to the medication mass per volume of solution:

Adrenaline concentrations can and do vary, but the following is a guide to concentrations and routes of administration for various indications:

| Concentration |

Route of administration |

Indication |

| Adrenaline 1:1000 |

Intramuscular Nebulised |

Anaphylaxis Croup Asthma |

| Adrenaline 1:10 000 |

Intravenous |

Cardiac arrest Cardiogenic shock |

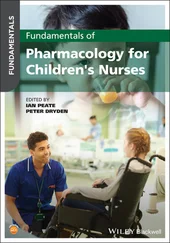

Administering medication to children

Historically, children were considered small adults, with the same physiology and metabolic requirements as an adult, but on a smaller scale. This is now known not to be the case, but many medications are still not tested on children, so safe doses in this patient group are not established empirically. A basic understanding of the differences between adult and child anatomy and physiology will ensure safer administration of medication to children. For example, the child’s heart does not have the same capacity to raise cardiac output by increasing its force of contraction and relies on increasing the heart rate to compensate for increased demand. As a result, peripheral vasoconstriction usually occurs more readily, in order to maintain blood pressure.

Medications which cause peripheral vasoconstriction need to be used with extra caution in children because of this. Adrenaline will cause peripheral vasoconstriction when used to treat anaphylaxis or asthma, and the beta‐2 agonist salbutamol (albuterol) is also often contraindicated in children because of the possibility of tachycardia. Using medications that cause tachycardia will place further demands on a child’s heart, possibly at a time when it is already working hard to compensate. These medications have to be dosed and administered with extreme care in children, and some may be contraindicated.

How is dosing calculated for children? If you don’t know the weight of the patient and there is no one to give you the weight, how would you estimate it, to ensure you give a safe and effective dose?

What special considerations need to be borne in mind when giving medications intranasally to children?

When administering medications to a child, ensure consent is gained from the parent, caregiver or a response given by the child is appropriate for their age and presentation. Ensure your approach to treating a child extends to providing oversight to the parent/caregiver as well.

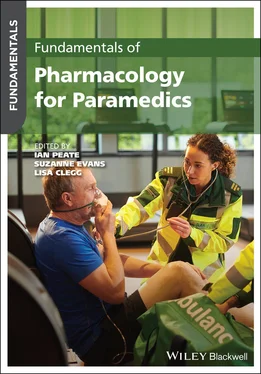

The out‐of‐hospital setting is not the same as the controlled environment of the hospital and the unpredictable and uncontrolled nature of paramedicine requires that the practising paramedic performs the work that would be done by three different health professionals in a hospital. This places a great responsibility on the paramedic when it comes to the safe and effective use of medicines. The paramedic must be an expert in both the correct choice and administration of medications. In addition, because the environment in which the paramedic is operating is particularly conducive to making errors, the paramedic must also be constantly vigilant and ensure the stringent and consistent checking of medication route, dose, time, expiration date and patient. As the scope of paramedic practice increases and more medications are administered in the prehospital setting, the need for paramedics to have a mastery of medicines becomes even greater.

AgonistA drug that binds to a receptor and produces the same response as the endogenous substance. For example, morphine is an agonist at opioid receptors because it produces the same response as the endorphins produce. AntagonistA drug that binds to a receptor and prevents the endogenous substance or an agonist from binding and having its effect. Also known as a blocker, because it blocks the activation of the receptor. ContraindicationA characteristic or condition which would prevent a patient from being able to receive a certain medication. First‐pass metabolismThe metabolism of a large proportion of an administered dose of a drug by the liver almost immediately after absorption. IndicationA condition or symptom which a medication is approved to treat. PharmacodynamicsThe actions of a drug on the body. PharmacokineticsThe actions of the body on the drug. ReceptorThe site at which a drug molecule binds to have its action.

1 Batt, A. Enhancing patient safety education for paramedics with the IHI Open School. http://prehospitalresearch.eu/?p=6171

2 Elliott, R.A., Camacho, E., Campbell, F. et al. (2018). Prevalence and Economic Burden of Medication Errors in the NHS in England. Sheffield: Policy Research Unit in Economic Evaluation of Health and Care Interventions (EEPRU).

3 Hobgood, C., Bowen, J.B., Brice, J.H., Overby, B. and Tamayo‐Sarver, J.H. (2006). Do EMS personnel identify, report and disclose medical errors? Prehospital Emergency Care 10(1): 21–27.

4 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada. (2020). Multi‐incident analysis of incidents involving paramedicine. ISMP Canada Safety Bulletin 20(1): 1–4.

5 Lammers, R., Willoughby‐Byrwa, M. and Fales, W. (2014). Medication errors in prehospital management of simulated pediatric anaphylaxis. Prehospital Emergency Care 18(2): 295–304.

6 McGovern, K. (1992). 10 Golden rules for administering drugs safely. Nursing 22(3): 49–56.

7 Nguyen, A. (2008). Bad medicine: preventing drug errors in the prehospital setting. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 33(10): 94–100.

8 Roughead, L., Semple, S. and Rosenfeld, E. (2013). Literature Review: Medication Safety in Australia. Canberra: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.

9 WHO Collaborating Centre for Patient Safety Solutions. (2007). Look‐Alike Sound‐Alike Medication Names. Patient Safety Solutions: Solution 1. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default‐source/integrated‐health‐services‐(ihs)/psf/patient‐safety‐solutions/ps‐solution1‐look‐alike‐sound‐alike‐medication‐names.pdf?sfvrsn=d4fb860b_6&ua=1

1 Australian Medicines Handbook (AMH). 2020 print edition or online: https://amhonline.amh.net.au

2 British National Formulary (BNF). 2020 print edition or online: www.bnf.org

Multiple‐choice questions

1 A medication error occurs when:The wrong dose is administeredA drug that would benefit a patient is not givenA drug that it not necessary is givenAll of the above.

Читать дальше