The present work departs from both early and recent findings on the materiality, historical context, and circulation of the manuscript as well from previous understandings of its contents, priorities, and reception. In doing so, this volume seeks to contribute to the aggregate of identities that historians have created for the Codex Mendoza, whether by simply changing the tempo and emphasis placed on the different episodes in the manuscript’s reproduction and circulation history, or by establishing a range of time for the production of the manuscript based on the dual axis of the codex’s historical context and inquiries into its materiality. Paraphrasing Daniela Bleichmar, this aggregate adds a new layer to the Codex Mendoza’s fluid ontology. This decision invariably underscores certain aspects of the manuscript that, notwithstanding their importance to the overarching history of the manuscript, in previous studies have played second fiddle.

Such is the case of the contrasting hypotheses on how the Codex Mendoza came to be in possession of its first known owner, French cosmographer André Thevet. Another important aspect of the manuscript’s history which has not been prioritized is Clavijero’s “invention” of the Codex Mendoza—relying on a widely known, yet anonymous source—during the eighteenth century. The first of these has been subsidiary to a history focused on demonstrating the connection between the manuscript and the first viceroy of New Spain since Clavijero’s aforementioned invention in the eighteenth century. As such, the “how” behind the Codex Mendoza’s arrival in France was shelved, relying on an account that, as we shall see, at best lacks support for its claims and, at worst, advances false information. In this essay, I argue for an alternative route of arrival that posits that the manuscript was initially available to a European context that was far wider than the viceroyal commission. However, at the same time, I acknowledge that, with the extant documentary evidence available, it is impossible to fully verify the manuscript’s initial trajectory. Likewise, I suggest that Clavijero’s decision owed more to his own literary agenda within the context of a proto-nationalist Mexican movement, than to the existence of any evidence tying the document to the viceroy.

The trajectory of the Codex Mendoza revisited

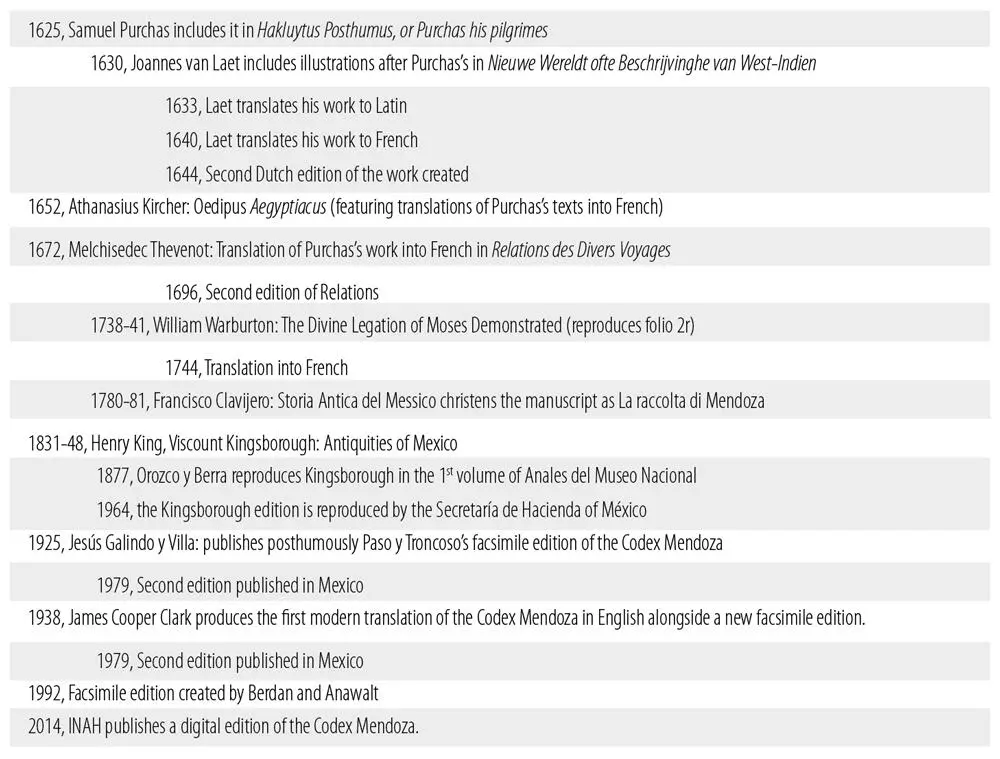

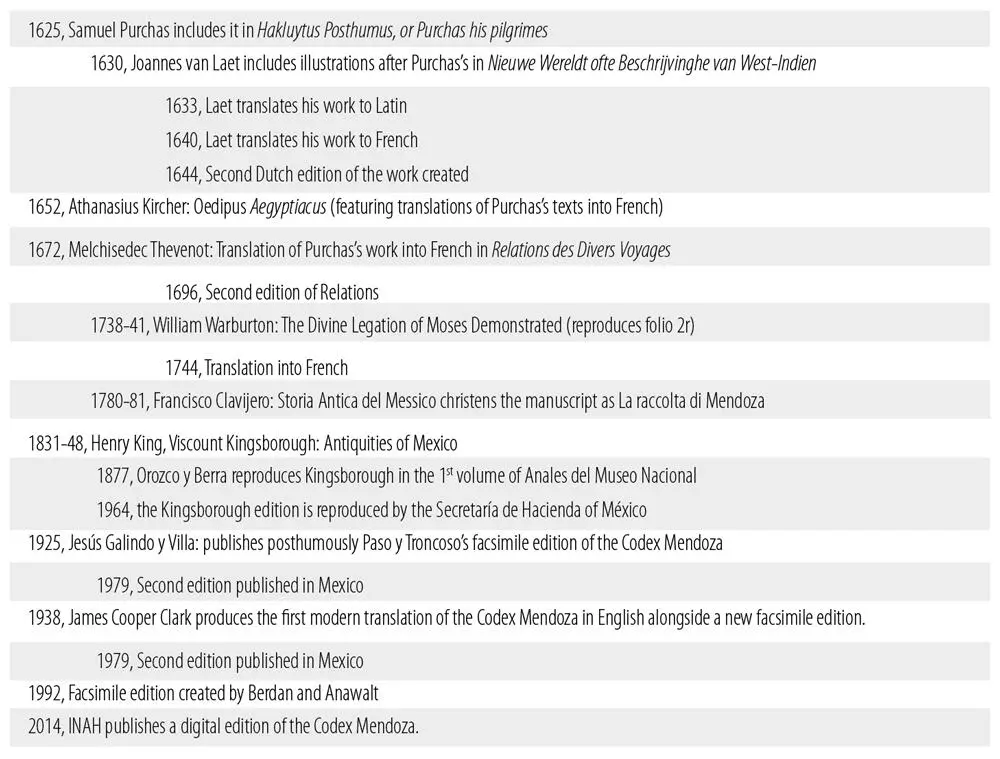

As the story goes, this manuscript was created by commission of don Antonio de Mendoza, first Viceroy of New Spain (r. 1535-1550), to be presented to Charles I of Spain. Instead, the manuscript ended up in France, where it was purchased by the cleric and geographer André Thevet (1516?-1592), who would work as geographer for four kings of the Valois-Angouleme dynasty, beginning in 1559. In the 1580s, the manuscript was passed on to Richard Hakluyt (1552-1616), a cleric and geographer who was also a secretary to the English ambassador to France, Sir Edward Stafford, between 1583 and 1588. After Hakluyt’s death in 1616, the manuscript passed on to another Englishman, Samuel Purchas (1577-1654), the first man to ever publish the texts and images in the Codex Mendoza, as part of his 1625 compendium of voyage chronicles Haklyutus Posthumus: Or Purchas His Pilgrimes. Finally, the manuscript reached its last private owner, John Selden (1584-1654), a jurist and scholar with an interest in ancient English and Hebrew laws, egyptology, and the pre-Columbian cultures of the New World (Toomer 2009). In fact, his library, which was bequeathed to the Bodleian Library after his death in 1655, included three Mexican manuscripts, the Codex Mendoza, which is the protagonist of this history, and two others: the Codex Selden, also known as Codex Añute, and the Selden Roll, also known as The Roll of the New Fire.4 Although his interest in pre-Columbian Mexico seems to have been tangential, Selden’s profile is worthy of consideration, since it is similar to those of scholars who will include the Codex Mendoza in their works for the two following centuries: thinkers interested in Mediterranean antiquity and how it was reflected conceptually—and sometimes practically—in the New World, Judaism and its impression on the development of Western thought, and natural history.

Table 1: Circulation, reproduction, and studies of the Codex Mendoza: 1625-1992

Despite the continuous reproduction and sustained circulation of the manuscript throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, two cardinal moments in the development of the modern history of the Codex Mendoza took place at the end of the eighteenth and at the beginning of the nineteenth centuries. In 1781, Francisco Clavijero, an exiled Mexican Jesuit living in Italy, identified the manuscript as “la colección de Mendoza” in his Historia Antigua de México. This led to the commencement of a new era of studies focused on the connection between the manuscript and the first viceroy of New Spain; these studies treated the Codex Mendoza as a document belonging to a foundational narrative that, even then, signals a fledgling Mexican nationalist movement. As we shall see, in the introduction to his Historia Antigua, Clavijero (1964) writes that his work will serve as a “first true history of Mexico, for the service of homeland and country”. In the same work, Clavijero goes on to announce that he had chosen forty-seven sources as the basis for this history, each of which had been painted by Mexican artists, written by notable colonial personages, or penned by authors whose texts fitted within a narrative with nationalist inclinations. Amongst those prominently featured, the one Clavijero identified as la colección de Mendoza is known today as the Codex Mendoza.5

In her analysis of Clavijero’s work, Rolena Adorno (2011, 15; see also Marchetti 1986) has highlighted that it “sought to recover the lost Mexican nation and defend it against the European Enlightenment thinkers who underestimated its worth and importance under the pretense of cultural and natural inferiority … often, Clavijero has been considered a precursor to Mexican independence. Doubtlessly, his ‘criollo’ patriotism and his apology of America in opposition to contemporary European thinkers have fixed the profile we recognize in his famous Historia Antigua de México”. In recognizing the role and ideological context of Clavijero’s works, and in particular of Historia Antigua de México and, consequently, of the Codex Mendoza, this work invariably fits within a genre of Latin American patriotic literature that Jesuit priests created towards the end of the eighteenth century (Brading et al. 2015, 34).

In 1831, Henry King, Viscount Kingsborough, brought the manuscript to the fore once more as part of a yet more ambitious narrative. Its inclusion in Kingsborough’s Antiquities of Mexico echoed one of the hypotheses that guided the evangelizing project of the sixteenth century: namely, the idea that the peoples of the New World descended from the lost tribes of Israel. This, in turn, led to a new era of reproductions of the Codex Mendoza. Accordingly, in the sixth book of Antiquities of Mexico, Kingsborough found reason after reason to aver that the peoples of Mexico descended from the lost tribes of Israel. If Clavijero’s actions ought to be understood against a backdrop of incipient independence movements that were beginning to take shape towards the end of the eighteenth century, the historical moment of Antiquities of Mexico places the Codex Mendoza within the context of the calls for emancipation of Catholics, Jews, and Africans within the British Empire.6

Throughout the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, Mexican academics, inspired by Kingsborough’s reproduction and probably by the foundational role Clavijero endowed the manuscript, used the Codex Mendoza as the axis for a series of political and historical publications rooted in the Mexican nationalist project that was taking shape at that time. Mexican nationalism of the era proceeded through a sequence of stages that included “criollo” imperialism, democratic sovereignty, European colonialism, and despotism.7 In 1877, during this last period, known as the “Porfiriato,” Manuel Orozco y Berra (1877, 185), the director of the National Museum of Mexico, inaugurated the Anales de Museo Nacional de México and published Kingsborough’s reproduction of the Codex Mendoza. In 1885, Antonio Peñafiel, working for the Dirección Nacional de Estadística de México (National Statistics Office of Mexico) and under the sponsorship of the Secretario de Fomento Mexicano (Development Secretary for Mexico), once again published the contents of the manuscript as part of his Nombres geográficos de México. As part of his work, he reproduced the place-name glyphs of cities and towns from the second section of the Codex Mendoza—which he labelled as “municipios de la república” (municipalities of the republic)—alongside a series of linguistic studies. In doing so, Peñafiel (1885, chap. 1) sought to arrange the political and economic geography of the modern Mexican nation around a project of recovery and reconstruction of the place-names for cities and towns of pre-Columbian Mexico.

Читать дальше