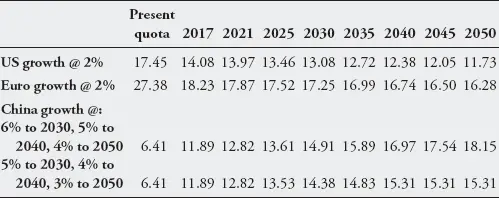

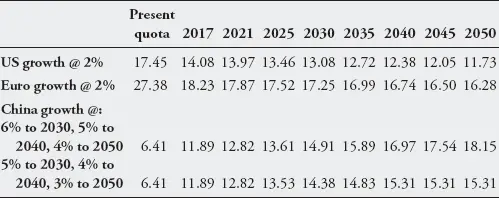

Table 1.1presents the current array of IMF quotas among the three largest currency issuers (United States, eurozone, China); a calculation of where they should be now if the formulas were applied faithfully; and projections of what the formulas would suggest for future quota allocation out to 2050 on the basis of our projections of economic and trade growth in chapter 3. They show that China is substantially under-represented now, would probably move into the top quota slot according to the formula by 2030 – ahead of the United States, and since the eurozone is not a country (see below) – and will clearly be in the lead by 2050 (even if its growth declines to 4 percent after 2030 and 3 percent after 2040). If the IMF and World Bank adhere to the mandates of their charters, China should therefore become the host of their headquarters by the middle of this century if the postulated economic developments come to pass.

Table 1.1 IMF quotas: Projections to 2050 on current IMF formula

Note: Assume openness, variability, reserves remain constant over time. GDP projections are from IMF until 2024. Starting from 2025, GDP growth rates are specified as in the table. Euro includes 19 eurozone countries: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain. Euro quota is the sum of quotas of these 19 countries.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook (October 2019).

The United States and some other IMF members, however, will undoubtedly insist on negotiating the terms of that shift to make sure that China would faithfully implement all fundamental IMF requirements, as they negotiated for 15 years on China’s entry to the WTO and are now seeking to negotiate changes in China’s trade policies before according it the promised “market economy status.” To avoid the cost and inconvenience of actually moving headquarters, China could of course ask for some other major recognition of its status, such as the selection of a Chinese national as Managing Director (De Gregorio et al. 2018). Other alternatives can also be envisaged, such as the proposal in the text ( chapter 10) that the quotas of China and the United States converge to equal levels over time, to recognize the rough equivalency that is likely to characterize their economic relationship in the decades ahead. Another possibility would be for China, if it continues to lead the world in providing development finance, to take the top spot at the World Bank while the United States stayed at no. 1 at the IMF (or vice versa).

A possible complication is the position of the eurozone. The 19 members of the euro area now have a combined quota much larger than the United States and would have a claim to become the new host “country” (Frankfurt? Brussels? Paris?) if they could agree to consolidate their representation and speak with a single voice (although the IMF charter refers to “member countries” and it is unclear whether a currency area would qualify). China’s projected growth path would not place it beyond the eurozone before 2050 if its growth rate were to drop to 4 percent after 2030 and 3 percent after 2040, so the “rough equivalency” formulation could apply to the zone as well as to the United States and China.

The trade war between the United States and China has obscured the more fundamental competition between the two countries for global economic leadership. History shows that conflict between rising China and incumbent power United States is a real possibility; there is clearly a risk of an economic variant (at least) of the “Thucydides trap” (Allison 2018). Power transition theory suggests that risk is greatest during the decade or two when the newcomer is approaching and reaching the level of the previous leader, which is right now and the years immediately ahead. Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, a China expert, calls this “the decade of living dangerously” (Rudd 2021).

The trade, investment, and technology wars of the last few years confirm that these risks are very real. US efforts so far have failed to restrain China or induce changes in Chinese policies that are needed to ease the conflicts. This competition is likely to be one of the most sustained, as well as most important, features of the world economy (and world politics more broadly) for the foreseeable future.

China is likely to continue growing at least twice as fast as the United States and the other high-income countries for at least another couple of decades. As chapter 3will show, it would then become at least roughly equivalent to the United States on most counts well before the middle of the century. Its catch-up pace accelerated with the coronavirus pandemic as its growth was curtailed much less than that of the United States and the other high-income countries.

China has become the largest engine of growth for the world economy. It replaced the United States in that role well over a decade ago, before the global financial crisis of 2008–9, but especially since. It has accounted for 25–30 percent of total world expansion over this period. It has already achieved global economic leadership in this important respect.

Size is, of course, not the only determinant of international economic power and leadership potential. China remains, on average, a relatively poor country with per capita incomes only one quarter that of the United States. On a “power index” that combines overall and per capita GDP, as described in chapter 3, China only reaches US levels toward the end of the century. American wealth far exceeds Chinese wealth. China has little soft power, and its authoritarian values, disregard for human rights, and relentless focus on the primacy of the Communist Party are not widely admired around the world. It enjoys no alliances with economically important countries, in contrast to America’s traditionally extensive networks.

But China is catching up rapidly or passing the United States on most of the economic metrics, enhancing its capabilities for global economic leadership. Its centralized political system enables it to mobilize the country’s vast resources effectively in support of agreed policy objectives. Neither China nor the United States can dictate to the other, as the currency negotiations of 2005–13 and the trade negotiations of 2017–20 so clearly revealed. Each can impede most of the other’s initiatives.

The United States and China together are likely to account for more than half the world economy by mid-century. Their cooperation is required to successfully resolve virtually all major international economic problems, from global growth to climate change. Their failure to cooperate will doom most such efforts.

The relative economic positions of China and the United States differ from issue to issue (Johnston 2019a). The dollar remains the world’s key currency and the United States maintains considerable monetary power, though China’s huge foreign exchange reserves and international creditor status enable it to wield sizable financial leverage as well. China’s huge market and prodigious competitiveness place it at or near the top on the macroeconomic and trade side. China has become the world’s largest donor of foreign aid, through its state policy banks and the massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and has attracted much support from poorer countries with its “develop economically and preserve your independence” mantra. The United States retains overall military primacy but China has caught up impressively, especially at the regional level. Technology is increasingly closely contested, especially with respect to cybersecurity and the Internet. The two economic superpowers have different capacities to lead the world in different issue areas.

Читать дальше