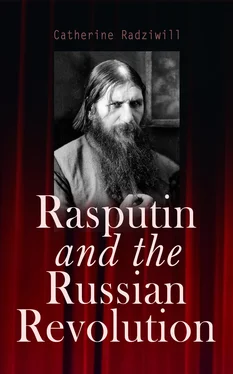

It was during this same winter of 1912–13 that the name of Rasputin became more and more familiar to the ears of the general public, which until that time had only heard about him vaguely and had not troubled about him at all. It was also then that rumours without number concerning the prayer meetings at which he presided began to circulate. Innumerable legends arose in regard to those meetings, which were compared to the worst assemblies ever held by Khlysty sectarians. In reality nothing unmentionable took place during their course. Rasputin was far too clever to apply to the fine ladies, whose help he considered essential to the progress of his future career, the same means by which he had subjugated the simple peasant women and provincial girls whom he had depraved. He remained strictly on the religious ground with his aristocratic followers, and he tried only to develop in them feelings of divine fervour verging upon an exaltation which was close to hysteria in its worst shape or form. In a word, it was with him and them a case like that of the nuns of Loudun in the sixteenth century. Had he lived in the middle ages it is certain that Rasputin would have been burnt at the first stake to be found for the purpose, which, perhaps, would not have been such a great misfortune.

Rasputin and His “Court”

Rasputin and His “Court”

I have seen a photograph representing the “Prophet” drinking tea with the ladies who composed the nucleus of the new church or sect, which he prided himself upon having founded. It is a curious production. Rasputin is seen sitting at a table before a samovar or tea urn slowly sipping out of a saucer the fragrant beverage so dear to Russian hearts. Around him are grouped the Countess I., Madame W., Madame T. and other of his feminine admirers, who, with fervent eyes, are watching him. The expression of these ladies is most curious, and makes one regret that one could not observe it otherwise than in a picture. Their faces are filled with an enthusiasm that bears the distinct stamp of magnetic influence, and it is easy to notice that they are plunged into that kind of trance when one is no longer accountable for one’s actions.

The method used by Rasputin was to humiliate all the women of the higher circles whom he had subjugated, and who had been silly enough to allow themselves to fall under his spell. Thus he liked to compell them to kiss his hands and feet, to lick the plates out of which he had been eating, or to drink out of the glass which he had just drained. He made them say long prayers in a most fatiguing posture, compelled them sometimes to remain for hours prostrate on the ground before some sacred image, or to stand for a whole day in one place without moving, as a penance for their sins; or again to go for hours without food. Once he commanded one of them to walk in one night to the village of Strelna, a distance of about twenty-five miles from St. Petersburg, and to return immediately, without giving herself any rest at all, with a twig from a certain tree he had designated to her.

In a word, Doctor Charcot would have found in him an invaluable assistant in the experiments he was so fond of making. But he did not go further than these eccentricities. Orgies did not take place during the prayer meetings in which Rasputin exerted to the utmost the magnetic powers which he undoubtedly possessed. While he had been preaching to the humble followers he had at the beginning of his career of thaumaturgy the theory of free love, to his St. Petersburg disciples he declared that sensuality was the one great crime which the Almighty never forgave to those who had rendered themselves guilty of it. It was in order to subdue the flesh and the devil that he commanded his victims to mortify themselves together with their senses, and that he submitted them to the most revolting practices of self-penitence before which they would have recoiled with horror had they been of sound mind.

There is a curious account of an interview with him which was published in the Retsch, the organ of the Russian Liberal party, immediately after the death of Rasputin by Prince Lvoff, who had had the curiosity to speak with the “Prophet.” The Prince was one of the leaders of the progressive faction of the Duma. This is what he wrote, which I feel certain will interest my readers sufficiently for them to forgive me for quoting it in extenso:

“I have had personally twice in my life occasion to speak with Rasputin. The first time was toward the end of the year 1915, when I was invited by Prince I. W. Gouranoff to meet him.

When I arrived Rasputin was already there, sitting beside a large table, with a numerous company gathered around him, among which figured, in the same quality as myself, as a curious stranger, the present chief of the military censorship in Petrograd, General M. A. Adabasch, who was the whole time attentively watching the “Prophet” from the distant corner whither he had retired. Rasputin was dressed in his usual costume of a Russian peasant and was very silent, throwing only now and then a word or two into the general conversation or uttering a short sentence, after which he relapsed into his former silence. In his dress and in his manners he was absolutely uncouth, and when, for instance, he was offered an apple he cut a hole at its top with his own very dirty pocket knife, after which he put the knife aside and tore the fruit in two with his hands, eating it, peel and all, in the most primitive manner. After some time he got up and went to the next room, where he sat down on a large divan with a few ladies who had joined him, toward whom his manner left very much to be desired.

I had kept examining him the whole time with great attention, seeking for that extraordinary glance he was supposed to possess, to which was attributed his power over people, but I could not find any trace of it or notice anything remarkable about him. The expression of his face was that of a cunning mougik, such as one constantly meets with in our country, perfectly well aware of the conditions in which he found himself, and determined to make the best out of them. Everything in him, to begin with his common dress and to end with his long hair and his dirty nails, bore the character of the uncivilised peasant he was. He seemed to realise, better perhaps than those who surrounded him, that one of his trump cards was precisely this uncouthness, which ought to have been repelling, and that if he had put on different clothes and tried to assimilate the manners of his betters, half of the interest which he excited would have disappeared. I did not stay a long time, and went away thoroughly disappointed, and perhaps even slightly disgusted at the man.

A few months later, in February of the present year, 1916, I was asked again to meet Rasputin at Baron Miklos’s house. There I found a numerous and most motley company assembled. There were two members of the Duma, Messrs. Karaouloff and Souratchane; General Polivanoff; a great landowner of the government of Woronege, N. P. Alexieieff; Madame Svetchine; the Senator S. P. Bieletsky and other people. Ladies were in a majority. Rasputin remained talking for a long time with the Deputy Karaouloff in another room than the one in which I found myself. Then he came to join us in the large drawing room, where he kept walking up and down with a young girl on his arm—Mlle. D., a singer by profession—who was entreating him to arrange for her an engagement at the Russian Opera, which he promised her to do “for certain,” as he expressed himself.

Every five or ten minutes Rasputin went up to a table on which were standing several decanters with red wine and other spirits, and he poured himself a large glass out of one of them. He swallowed the contents at one gulp, wiping his mouth afterwards with his sleeve or with the back of his hand. During one of these excursions he came up to where I was sitting, and stopped before me exclaiming: “I remember thee. Thou art a gasser, who writes, and writes, and repeats nothing but calumnies.” I asked the “Prophet” why he did not say “you” to me, instead of addressing me with the vulgar appellation of “thou.”

Читать дальше

Rasputin and His “Court”

Rasputin and His “Court”