2.3.1.3 SELF-ASSESSMENT OF ABILITY

Another way of considering this journey of skill development is the so-called “Dunning-Kruger Effect” (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). This describes a form of cognitive bias that leads to individuals overestimating their own ability because they lack sufficient knowledge and understanding of what they are doing to realistically measure their level of skill. It is only through painful discovery of the limitations of their ability that they can begin to learn. This correlates well with the unconsciously incompetent level described above. It is also a potentially dangerous issue with a novice clinician involved in providing a potentially complex treatment to a patient.

Training in implant dentistry is provided at a number of levels. At its simplest, clinicians learn from each other as they progress along the learning curve. This is the process by which most of today’s acknowledged “experts” learned these skills in the period during which implant treatments were evolving.

With implant dentistry now an established discipline, learning from shared experience is valuable for clinicians who have a sound understanding of implant treatments. Here, the consciously and unconsciously competent clinicians can benchmark their understanding against that of others.

However, this approach is unlikely to be effective if the individuals (eg, those in the unconsciously incompetent group) sharing their experiences do not fully understand the significance of what these experiences represent. This model is often popular today with younger practitioners who learn from colleagues via online forums, but this represents a real risk of being “the blind leading the blind.”

2.3.1.5 SHORT TRAINING COURSES

Similar observations might be made about the short, companyled programs. Often the aim of this training is to make practitioners aware of the processes needed to handle that company’s componentry, and thus these programs often focus on the “how” rather than the “why” or “why not.” Also, due to the brevity of these courses, the biologic and biomechanical principles involved in implant treatments must be greatly abbreviated or are simply not covered at all. Unfortunately, this method can be fraught with danger to patients and cannot allow for a focus on best-practice protocols, as these concepts may be unknown to those learning.

2.3.1.6 STRUCTURED EDUCATION AND TRAINING

The most effective training comes from structured programs that provide a sound basis for patient selection and treatment. These courses address the basic sciences that underpin successful treatment, introduce protocols for patient assessment and selection and treatment planning, and then provide candidates with the opportunity to perform actual treatment and patient maintenance with assistance and guidance from more experienced mentors. Given the breadth of the topics to be covered, these programs must extend over longer periods compared with other approaches. Thus, these programs can be expensive in terms of time and money and difficult to fit in alongside daily practice, leading to under-utilization of this type of education and training.

Intuitively, one might expect that better-quality training would result in fewer complications or failure. While this is generally accepted in health care, little evidence is available to support these conclusions. Certainly, patients and regulators see this connection as true, and this forms that basic assumption that underpins mandated continuing professional development requirements.

2.3.2 Reducing clinician-related risk

2.3.2.1 RECOGNIZING “HUMAN FACTOR” RISKS

What have been described as “human factors” are becoming recognized as sources of error in health care provision. Much of the research in this area comes from the commercial aviation industry, but these findings are beginning to permeate into health care safety considerations.

A second edition of Renouard and Rangert’s book about risk factors was published in 2008 (Renouard & Rangert, 2008) and brought the topic of experience and human factors to the discussion.

In a recent review of these factors and their influence in dental implantology, Renouard and coworkers (Renouard et al, 2017) described five hazardous attitudes or behaviors that are potentially detrimental to safe practice. Originally identified in aviation, these types are:

1. ImpulsivenessThe urge to get things done quickly, without necessarily considering potential dangers.

2. Anti-authorityThe attitude held by some practitioners that rules, regulations, and protocols are for others, and do not pertain to them.

3. InvulnerabilityPractitioners who believe that adverse outcomes only happen to others, and not to them.

4. MachoThe belief that a practitioner must be constantly demonstrating their superiority over others. While this is mostly a male trait, it can affect women as well.

5. ResignationThe belief that no matter what a practitioner does, it will not have any effect on the outcome.

2.3.2.2 STRESS AS A RISK FACTOR

Renouard and coworkers also discuss stress as a potential problem. While the stress response is adaptive (ie, it is protective against external threats), it can have negative effects in a health care setting where the stress is mostly self-induced. Stress factors such as time pressures, staff problems, and interpersonal frictions between the dentist and the patient can all have a negative effect on performance. Stress tends to reduce the practitioner’s ability to rationally think through a problem and rather promotes the use of automatic responses, which may be incorrect or unhelpful. These factors are well studied in the medical literature as well, as it relates to many daily issues, like less sleep, financial problems, and health or family issues (West et al, 2006).

2.3.2.3 MITIGATING THE HUMAN FACTOR ISSUES

To counter these “human factor” issues, Renouard recommends using techniques that have been developed for the airline industry to address safety problems: so-called “crew resource management.” The concept of the “sterile cockpit” where all extraneous activity is banned during high-risk periods, such as take-off and landing, can be transferred to the dental implantology setting for use during critical periods of treatment provision. Strict division of responsibilities between team members also reduces stress and “information overload.” Additionally, checklists can be very useful in concentrating attention on critical steps, especially in highly procedural tasks such as those seen in medicine and dentistry. This approach has also been promoted by other authors (Gawande, 2009; Pinsky et al, 2010). Here the SAC classification can be used as a checklist to ensure that all factors relevant to the patient’s presentation are assessed and incorporated into treatment plans.

2.3.2.4 CLINICIAN RISK FACTOR IN RELATION TO OTHER SOURCES OF risks

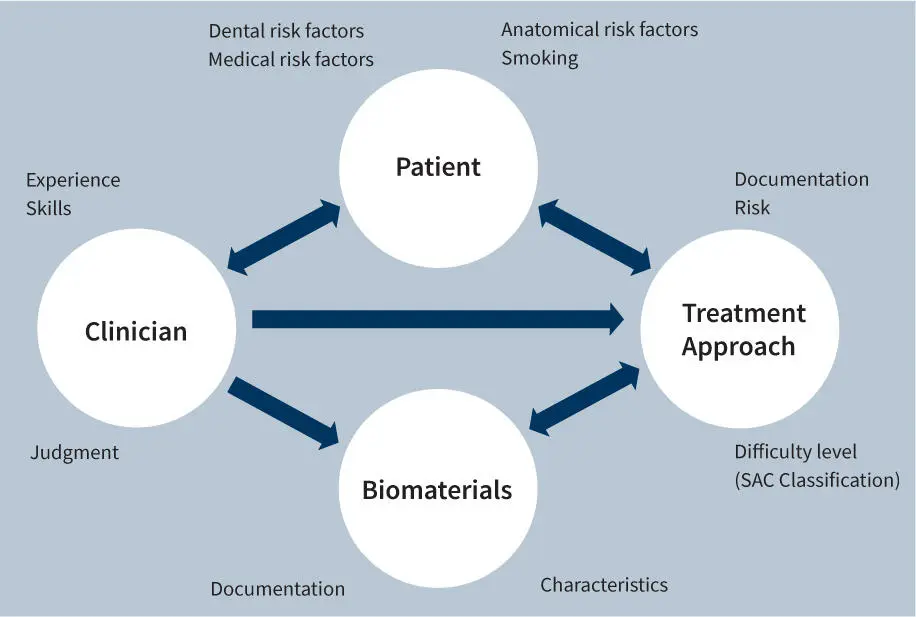

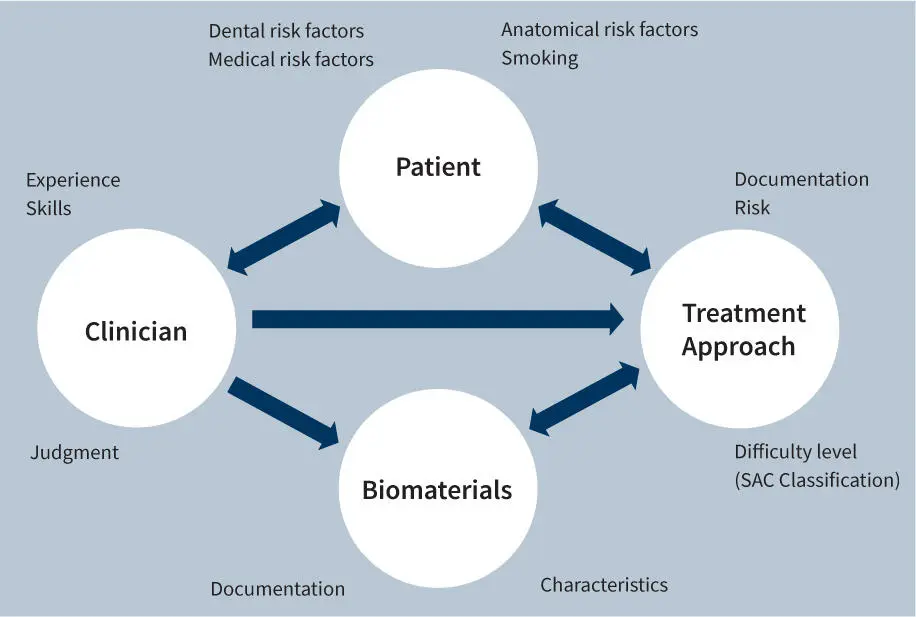

The clinician is central to most decisions and their practical application in implant treatment. Risks in implant dentistry can be attributed to four main sources: the patient, the treatment approach, the biomaterials, and the clinician. This relationship between the clinician, the materials, and the patient factors was first described by Chen and Schärer in 1993 (Chen & Schärer, 1993). Further, Buser and Chen (Buser & Chen, 2008), published on a model that also illustrates the potential interactions between these factors, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig 2.Potential sources of risk (Source: ITI Treatment Guide Vol. 3 “Implant Placement in Post-Extraction Sites”)

Читать дальше