1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...19 Helen found another figure that she liked from a German source ( Figure 11). She used her smart phone to access an online translation program to get the English meaning of the terms that appear around the figure: feucht = wet; trocken = dry; kalt = cold.

Figure 11. The four classical elements of the ancient Greeks

“Let me guess,” Marie said. “Warm equals warm, right?”

“Yes, of course,” Helen said. “And here around the circle, starting at the top, we have the usual Air, Fire, Earth and Water. Except for the Luft, it is pretty clear that old English is a Germanic language.

“The basic terms that the common people used are very similar to present day German. I understand that it was only after the Norman Invasion in 1066, that the language of the Court became French and all those Latin derivatives began to creep into the everyday English language.”

“I’m getting a pretty clear picture of what was going on,” Marie said. “Latin was the language of scholars in the Middle Ages, and their use of the Latin term Essentia for the four elements that they recognized reminds us that their meaning of the word element differs quite a bit from the meaning of today's term: chemical element. The term chemical element designates an individual pure substance, such as copper, silver, gold, mercury, or sulfur, but like Professor Wood told us, the Essentia were more like States of Being in the course of nature. In the Middle Ages a lot of mystical stuff was attributed to the four-element theory.”

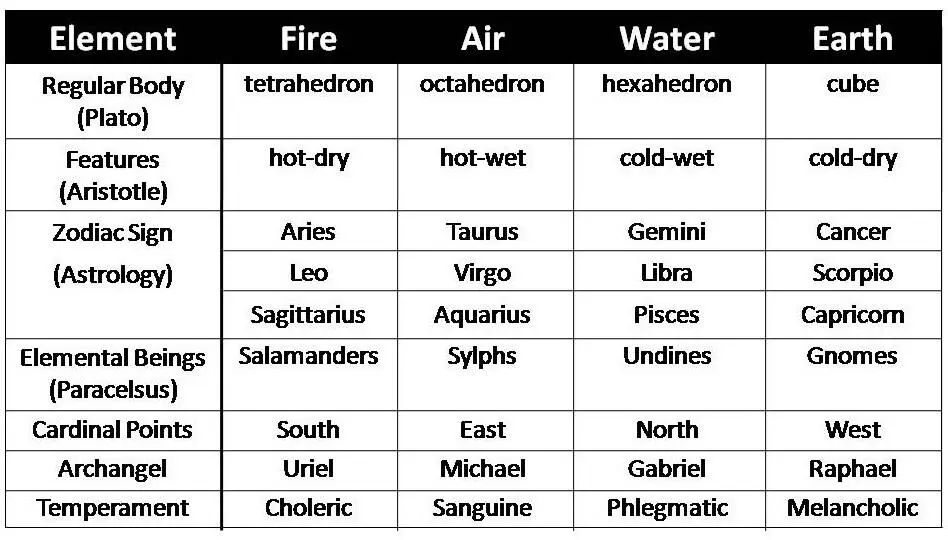

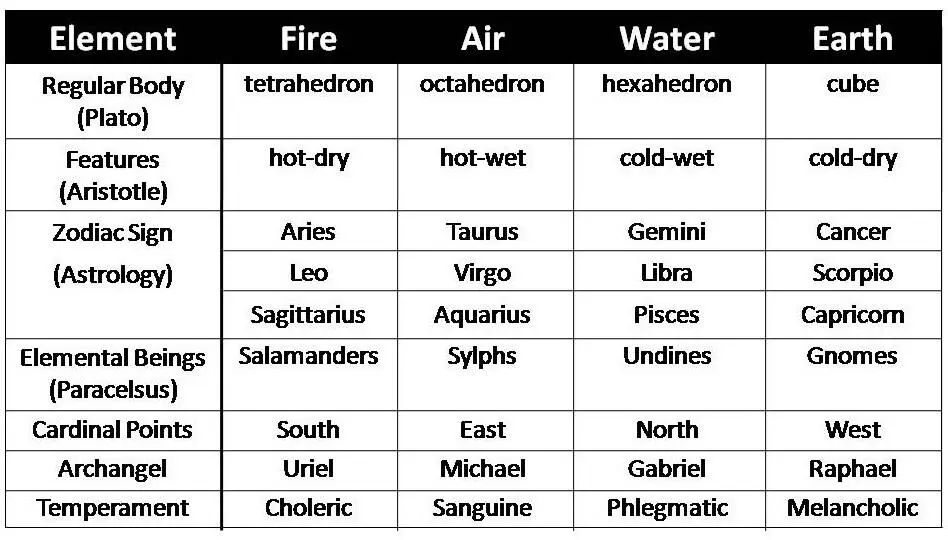

They went to another webpage. Marie pointed out an interesting table on one of them ( Figure 12).

Figure 12. The Four Elements in the Middle Ages

In addition to recognizing the regular Platonic bodies and the thoughts of the school of Aristotle in which the four elements relate to various mixtures of the four states hot, dry, wet and cold, Paracelsus added his nature spirits such as salamanders, sylphs, gnomes and undines. Sometimes the four elements were also associated with the four Archangels Uriel, Raphael, Gabriel and Michael. Even the different types of human temperament that the ancient recognized: choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic and melancholic; were assigned to the four basic elements.

“I’m going to download this table to bring with us next week when we meet with Professor Wood,” she said.

“Helen,” Marie asked as she looked across the row of Paracelsus's elementalbeings “do you know what an Undine is?”

“I do!” Helen replied, “It is a female water spirit that lives in lakes and streams and is attracted to human beings. I’m not real clear about the difference between an Undine and a Mermaid, except that the latter seem to live in the ocean. Maybe Paracelsus was not acquainted with the open sea or maybe Mermaids were from a more Nordic mythology. In any case, Paracelsus needed a spirit to represent water and this seems to be the one that he chose. I think the name derives from the Latin word for wave . Undine sounds more mystical to me and, as such, it is a better match to alchemy as far as I am concerned.”

What is the quintessence?

True to her word, Marie brought up the table that she and Helen had found as soon as they had entered Professor Wood’s office.

“Look at what we found,” she exclaimed.

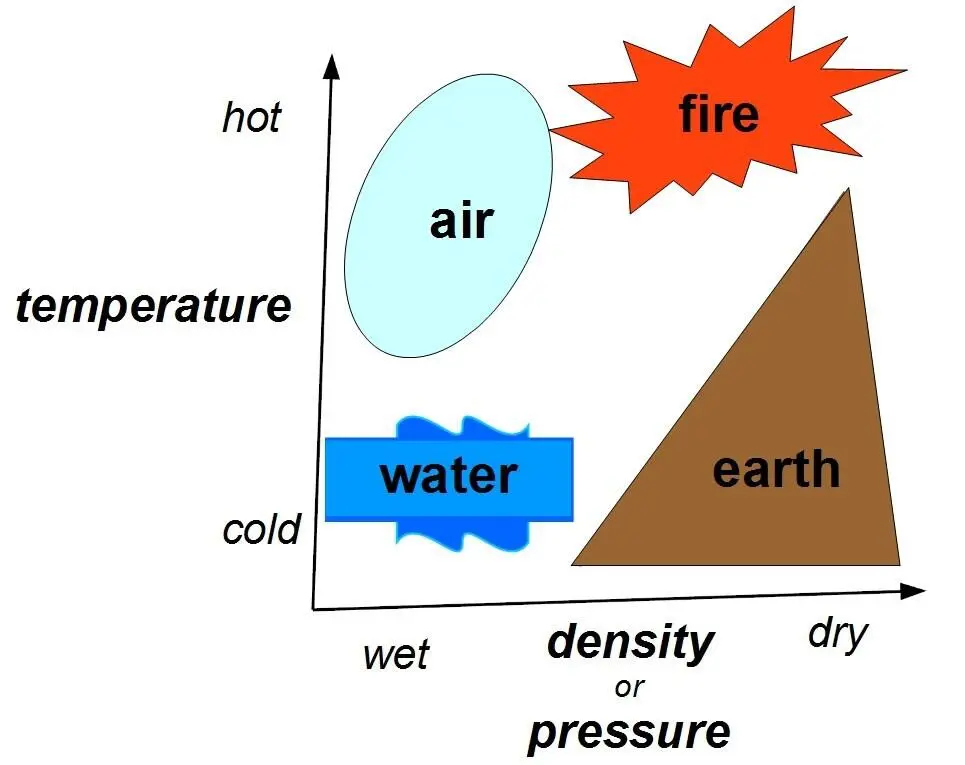

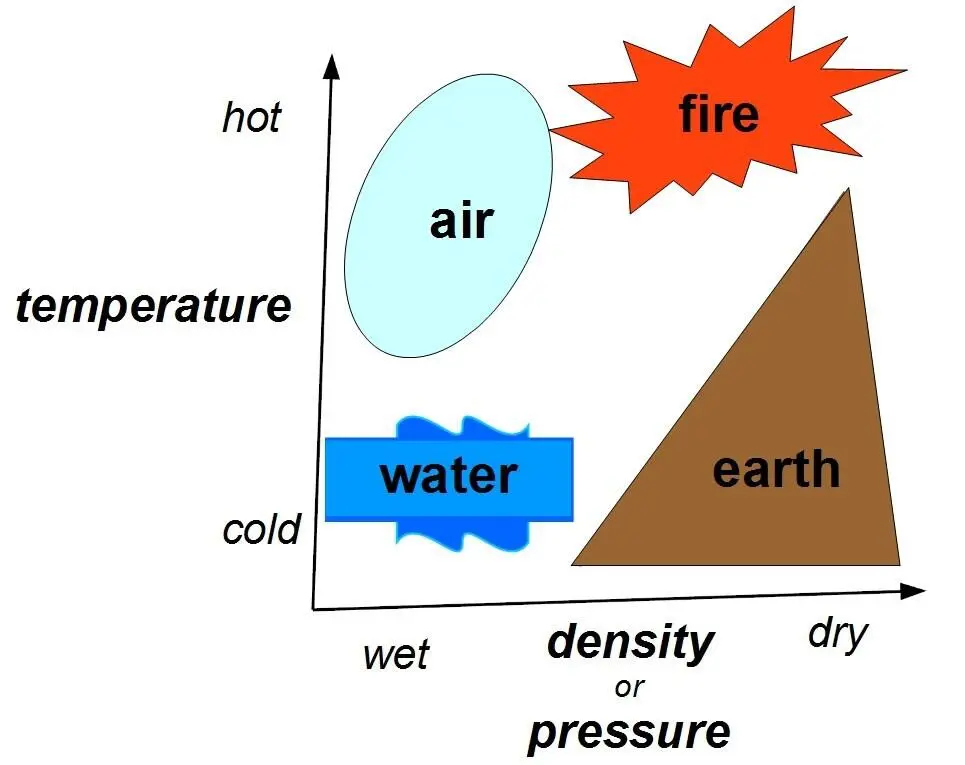

Professor Wood took a moment to study the relationships that appeared on Marie’s smart phone. He nodded approvingly. “Let me show you the way that a modern alchemist might view this table.” He sorted through the sheets on his desk until he found one with bold, colorful icons. ( Figure 13)

Figure 13. The four essentia shown differently

At the sides of his figure he had included the perceptions of Aristotle: cold-hot and wet-dry. The arrow from cold to hot pointed in the direction of increasing temperature. He explained that in his figure the arrow from wet to dry represented more of an increase in the density of the substance than it did actual moisture content.

“So here’s the thing,” he explained carefully. “I consider an increase in density to be equivalent to an increase of pressure within the substance. Of course, the ancients recognized, as we do, that some substances naturally have more mass per unit volume than do others. And that concept still fits both the modern and the historic views of this diagram. But it fits especially well with my work to take pressure as the horizontal axis. That way I am able to include changes of density within a single substance that are due to an externally applied pressure.

“You see, we can change the nature of a substance by heating it or by applying external pressure, or both at the same time! It is in that sense that the modern alchemist follows the practices handed down to him through the ages. It’s just that, in my case, we go to greater extremes in these dimensions from very cold to very hot and from partial vacuum to thousands of atmospheres of pressure.

“The other thing we do differently these days is that we make precise measurements using modern techniques and instrumentation. We also communicate our results openly using agreed-upon units of measurement and standard terminology. These more modern practices were introduced into the study of natural sciences at the time of Galileo Galilei around 1600 AD. Galileo should have said that we should measure everything that we can measure and what we cannot measure, we should make measurable.”

“So, if I follow you correctly,” Helen interjected, “you are saying that Galileo ushered in a whole new era of scientific observation and reporting.”

“That is exactly what I mean,” the professor responded. “And that is why most scientists today consider Galileo to be the father of modern science .”

“But you still think of yourself as somewhat of an alchemist, right?”

“I do,” agreed the professor. “And I hope that I can explain that more fully to you and Marie. But first, let me ask you what might be missing in this picture.”

“I remember that when we first discussed the figure with the triangles ( Figure 4), the four regions of this diagram appeared at the corners, but there was one in the center that you described as representing the Materia Prima ,” Helen said. “I think that you said that the middle symbol corresponded to a superposition of the other four – or maybe that the other four had been derived from the central figure. Then, when we were discussing the diagram from Basil Valentine (Figure 5), you said something like ‘Out of formless matter, the universe became organized into four basic elements.’ So what seems to be missing from this diagram is a region corresponding to the original heavenly matter of the Confusum Chaos .”

“Very good!” exclaimed the professor. “What also does not appear in this chart is a fifth element, a fifth essence, the quinta essencia in Latin.”

“Oh, so that is where we get the adjective ‘quintessential’ to describe the most fundamental example of something, as in ‘the quintessential question is ….,” Marie chimed in.

Читать дальше