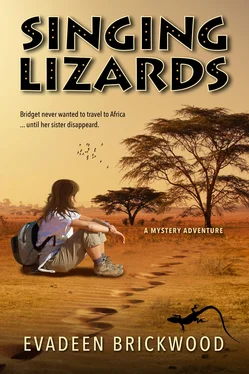

Evadeen Brickwood - Singing Lizards

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evadeen Brickwood - Singing Lizards» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на немецком языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Singing Lizards

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Singing Lizards: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Singing Lizards»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Singing Lizards — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Singing Lizards», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Tony laughed the whole thing off.

“Her nose is permanently out of joint,” he said. “Ethel Poppelmeyer is a very lonely woman. All of her maids run away after a few days. She seems to think that she’s the lady of the manor around here, surrounded by lowly serfs.”

“Just that there is no manor here. And no lowly serfs.”

“Exactly.”

“Maybe she’s just in the wrong place, you know. Some people don’t easily adjust,” I offered.

“Probably more ‘wrong century’,” Tony grinned.

Palapye was not exactly the lively place I had pictured in my mind.

No teeming marketplaces, no riotous music and dancing and no smiling fishwives in colourful garb. The locals could be rather shy until sorghum beer got the better of them.

And not one single African warrior in sight, who remotely resembled Shaka Zulu in the video-series. And nobody wore such creative, African attire I had seen on film.

There was just a lot of red earth, grey sand, dusty plants and searing heat. Only very few people to speak to, but far too much time to think.

Mrs. Poppelmeyer did me the honour of another brief visit about a week later. For lack of another listener, she complained to me bitterly about her gardener, who had torn a pair of work pants. He had not returned after she took 10 Pula quite rightly off his monthly pay.

Never mind that the poor chap only earned about 50 Pula a month and needed to feed his family. 10 Pula was a fortune to some in 1988. About 1 Pound Sterling if I remember correctly. A fortune for a simple gardener.

“When my husband and I lived in Bolivia, where he was of course the principal of a very large college, servants were so much easier to handle. My husband would just say ‘Hey chico, come here and do that’ and the servant would obey. But these blacks are so difficult —,” she grumbled.

I kept my peace and went back to my garden work, giving Ethel some excuse that Tony expected me to finish the planting by the end of the day.

Ethel didn’t speak to me again. I just heard rumours later that she had returned to Cobblestead for good, leaving her oh so hardworking husband to his own devices in the African wilderness.

Another neighbour had come back from England. Alfred Jones lived next-door. He was the woodwork instructor and one of a kind. His heavily pregnant wife had stayed behind in Cardiff.

Alfred was quite a character, burly with a mop of unkempt grey hair and a big wiry beard hiding most of his face. He wrote to his wife Judith every day. Usually in the afternoon before downing a few beers on his porch. He often gave me a lift to the police station when he posted the letters. Alfred Jones also sometimes competed with me for telephone time at the Botsalo Hotel.

Now and again, Tony invited him over for a chat to help ease his loneliness. It was a sight to behold, when our neighbour got onto his footstool and climbed clumsily over the fence with a candle in his hand. Power cuts were frequent.

On one such occasion, he had even grabbed my hand in the darkness and held it tight — drunk of course. He didn’t remember afterwards, but Tony had requested that Alfred should bring a candle with him.

The beginning of the term drew closer and the wives of two Tswana teachers were setting up home in the complex. They were busy with meal preparation for their extended families all day long.

Mieliepap, the staple food, was cooked in three-legged black pots in the garden. The stiff mash was made from crushed white maize and the wooden stomping sounds never ceased. Surely driving Ethel Poppelmeyer around the bend.

The pap was often eaten with marogo, wild spinach. The women also had to run after their brood of children and wash everybody’s clothing. Or they supervised young girls doing these chores for them.

Unfortunately, there was an insurmountable language barrier between us.

My Setswana was non-existent, which put paid to a meaningful conversation. At least Mrs. Matija, a matron with five young children, managed to say Hello in English, while giggling and staring at her feet.

“Good morning, Mrs. Matija, how are you? Oh, is this your youngest? Hello.”

“Good morning, Miss Reynole.” That was usually it.

Her husband was one of the heads of department at the training centre. A position he assumed with dignity and a sense of tradition.

By now, I’d had to make peace with the fact that I would be staying longer than expected and I realised that I had to learn how to speak Setswana.

Tsanana, our maid, came up from the village every day to clean for both Alfred and Tony. She was the only female I could have a meaningful conversation with. Tsanana had been to school and — lucky for me — spoke some English.

She cleaned the house and taught me the bare basics of Setswana: “Dumela mma - Good day ‘m'am.”; “Dumela ra - Good day sir.”; “Le kai? How are you?”; “Re teng - I’m fine.”; “Ke utlwa Setswana gologonje - I understand a little Setswana.”

I had to repeat the phrases parrot-fashion. But she never grew impatient if the words didn’t roll easily off my tongue. Oh, all those harsh ‘g’ sounds. And then those little intricacies, such as pronouncing ‘ph’ as ‘p’ and ‘sh’ like ‘s’ and that a ‘he’ often became inexplicably a ‘she’.

Finally I could say a simple greeting in Setswana: “Dumela”. Not enough for a conversation yet, but a good start. In the afternoon the rain drummed onto the tin roof and we had to shout at each other.

“Tsanana, why don’t people look at me when I speak to them?” I asked. This curious habit of Tswanas staring at their toes had puzzled me for a while.

“No madam, she look at feet, because she respect!” Tsanana explained.

This was of course against the very principle of respect in western communication. Tsanana still called me madam. African hierarchy rules were rather strict. She looked at me in wide-eyed horror when I told her to call me Bridget.

‘Oh madam, I cannot call Mma Bridget. Must have respect,” she told me.

She also refused to eat with me in the same room never mind at the same table. Instead she preferred to sit on the kitchen floor. The floor was admittedly very clean, but I still didn’t understand. Tsanana insisted that it simply was her custom. She had to show respect. As her employers, we were like her elders. That’s all there was to it. If anyone found out that she didn’t respect us, she’d be in trouble. I gave in reluctantly.

Communication with England was dragging. Apart from the phone calls, letters were my only lifeline to the outer world.

Despite a considerable delay, they kept me up to date with news from Cambridge.

That’s how I found out from Zaheeda that David had a new girlfriend. I knew Pippa and that she was nowhere near as stroppy as yours truly.

Good, David had found his match. No jealousy, not even a twinge of pain. Just a little homesickness. What I missed sorely by now were pubs and cinemas. And to my great shame I had to admit that I missed British television.

But the more I got into tune with my African surroundings, the less I thought about pub grub and the next episode of Coronation Street.

I wrote back diligently. About the birdsong in the mornings, Tony’s garden and the stony smell of the savannah. About Mrs. Poppelmeyer and how noisily Tswanas spoke to each other in the streets.

They wanted to know my as yet unsuccessful search for Claire. Just how was I supposed to explain the insurmountable obstacles piling up in front of me?

How naïve I had been. One couldn’t just take a bus or train. In Palapye was simply no infrastructure to speak of.

Bobonong was apparently close by. I wanted to go there. And from there to the Tuli Block. But even if I had a car, taking the tedious trip through rain and mud on my own was likely to be crowned by failure.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

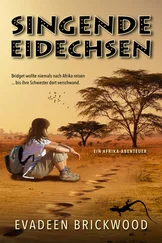

Похожие книги на «Singing Lizards»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Singing Lizards» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Singing Lizards» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.