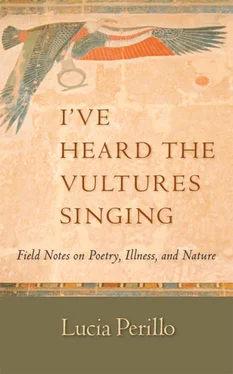

Lucia Perillo

I've Heard the Vultures Singing: Field Notes on Poetry, Illness, and Nature

Everything in nature is lyrical in its ideal essence,

tragic in its fate, and comic in its existence.

GEORGE SANTAYANA

These essays first appeared, in earlier drafts, in the following books and journals: American Poetry Review, Georgia Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Northwest Review, poemmemoirstory, River Styx, Short Takes: Brief Encounters with Contemporary Nonfiction , and Tin House. I would like to thank the editors of those publications for their scrupulous attention to my prose, and thanks also to the other people who looked at these essays as I thought my way through them: Ed Brunner, Scott Chambers, Sandra Fisher, Angus Heriot, Dorianne Laux, Maria McLeod, Marva Nelson, Suzanne Paola, James Rudy, Ben Sonnenberg. Steve Howie is the person to be either thanked or blamed for first suggesting to me that my life was interesting when I never would have thought it so.

Right now, a tiger named Andrea who lives in the Portland Zoo is dying of cancer in her uterus. The zookeepers might have caught the disease earlier if only she hadn’t kept it hidden, but animals are programmed not to give away their symptoms lest their predators take notice and begin the chase. There is a biological imperative that drives us not to show any traces of our pains, not to reveal any clues about our grip on existence having weakened. In the wild, the lame are quickly eaten, an efficient solution to the problem of disease, without even a need for cleaning up, thanks to the carrion-eaters and then the microbes.

It’s probably because I studied wildlife biology in college that my mind tends to drift in the direction of wondering what my life would be like if I were a wild animal. As a young woman, I worked as a ranger in a variety of wildernesses, and I was vain about having a body that could paddle me across the sea or climb me to the top of mountains without complaint except sometimes a little twinkling in the balls of my feet. When these sensations became more electrical, when the fog out of which I’d always built my daydreamswas pierced at odd moments by a fork of lightning, I found myself lying for half an hour inside a machine that clanged as if it were being pounded by a hammer. Since this imaging technology had only recently become available and the hospital in my town did not yet own such a machine, I’d entered one that pulled into town on a tractor-trailer, like the circus. So as not to blur the image, the technician warned me not to flinch.

A week later the photographic sheets were developed, revealing many cross-sections of my brain, laid out in columns and rows that had been marked with arrows, which pointed to white spots that the neurologist said indicated damage. That was when he named the disease, my disease as we say, as if having a disease conferred a kind of ownership, which would imply some degree of control. The name is made of syllables that are not suited to poetry. Leukemia, Lupus, Spanish influenza : any of these I could maybe do something with. But multiple sclerosis is just not workable from a poet’s point of view. In addition to that, it frightened me. For years I could not bear to see the word multiple printed anywhere, or my bones would dissolve and my lungs would refuse to be inflated.

The day after the doctor told me what had gone wrong with my body, I went skiing alone on Mount Rainier, where just a few months before I’d worked as a back-country ranger and had mastered the art of making those delicate telemark turns that require dropping to one knee like a man proposing with a ring. The new snow was thick and wet, what people call Cascade Concrete, and avalanche warnings had been posted at the ranger station. I had a dramatic idea about dying in an avalanche as I skied down the saddle between two peaks in the Tatoosh Range. To be packed like a supermarket fish in snow — I wanted to ride out of the world that way, and I drove home feeling a little disappointed about not being dead (but exhilarated, too, about having outwitted my bad number).

That last sentence included the kind of sentiment ( I was a little disappointed about not being dead ) that comes off as antisocial, living as we do in an age that mandates soldiering onward in the face of illness. The sick tiger walks the length of the bars in her cage in the zoo as if nothing’s wrong, and we humans ask each other how we’re doing every day; as a chorus of millions chants, Fine. It’s as if we have transposed the animal imperative not to expose our weaknesses, from body-language into words.

But to resist enlisting as a brave soldier in the battle against one’s illness — to choose instead burial by avalanche! — seems to me to be a typically human and honest response (or the honest response of one typical sort of human) to the news that one’s life might be marked by faster-than-normal physical decay. The doctor’s operative word was might , and the uncertainty was what I found unbearable in those early days when I hunted for a story or a portent in any form — tarot cards or tea leaves — to tell me about my future.

The only story I found useful was one by Jorge Luis Borges in which he describes the infinite Library of Babel. It’s a place that turns some men into murderers and drives others mad as each one searches for his own Book of Vindications, which will tell him the story of his death at the same time as it forgives him of his wrongs. But the infinite number of books in this library makes the hunt futile. There are too many books to search through. I bring up Borges’s story by way of saying that anyone looking to find his or her body here should be forewarned that this particular ride has already been taken.

In fact, my version of my illness has left me — slowly, over the course of twenty years — ever more physically compromised, and I have felt deficient of both willpower and spiritual vigor in being unable to control the slip and swoop and skid. To speak of this does not seem seemly because our tribe likes to hear stories of the body rising; perhaps this, too, is a remnant of that old necessity to not lure the wolves.

Foolishly, then, I leave this record of my recent years, of my life indoors and out. At times I think I’m barely living; I can hear the air being stirred by the vultures that circle overhead, and then zing —an eagle will battle a seagull over a stickleback, right in town beside the abandoned fried-chicken restaurant. Then my presence is confirmed, in the same stroke as the world says: you are not done here yet.

The painter Willem de Kooning famously called himself a slipping glimpser , slipping into the glimpse — slipping toward the image — that he would then arrest in paint. I spend much of my time trying to write poems about what I can single out from my own slipping, which is difficult because when you’re slipping you tend to keep your eyes trained on your feet to keep from crashing; it’s hard to lift your eyes so that the world can be attended to. Easy to forget, the world is still occurring outside the drama of the self, and the poem of the self is going to be limited unless the world can enter in. The down-tug of disease also tends to turn the glimpse into a blur, because the observer is in constant motion. How to capture the glimpse, to freeze it and make it legible? Or should the glimpse be captured in a manner that somehow incorporates the blur, the way that de Kooning’s paintings are all swirl and motion?

Читать дальше

![Various - Birds and Nature, Vol. 12 No. 5 [December 1902]](/books/745517/various-birds-and-nature-vol-12-no-5-december-thumb.webp)

![Various - Birds and Nature Vol. 11 No. 2 [February 1902]](/books/745533/various-birds-and-nature-vol-11-no-2-february-1-thumb.webp)