And the last Frontiersman, its offspring, driven back further and further towards the North into the far-flung reaches where are only desolation and barrenness, must, like the forest that evolved him, bow his head to the inevitable and perish with it. And he will leave behind him only his deserted, empty trails, and the ashes of his dead camp fires, as landmarks for the oncoming millions. And with him will go his friend the Indian to be a memory of days and a life that are past beyond recall.

CHAPTER TWO – THE LAND OF SHADOWS

"Full in the passage of the vale above

A sable silent solemn forest stood

Where nought but shadowy forms were seen to move."

Side by side with the modern Canada there lies the last battle-ground in the long-drawn-out, bitter struggle between the primeval and civilization. I speak not of those picturesque territories, within easy reach of transport facilities, where a sportsman may penetrate with a moccasined taciturn Indian, or a weather-beaten and equally reticent white man, and get his deer, or his fishing; places where, in inaccessible spots, lone white pines, one-time kings of all the forest, gaze in brooding melancholy out over the land that once was theirs. In such districts, traversed by accurately mapped water routes and well-cut portages, all the necessities and most of the luxuries of civilization may be transported with little difficulty.

But to those on whom the magic lure of far horizons has cast its spell, such places lack the thrill of the uncharted regions. Far beyond the fringe of burnt and lumbered wastes adjacent to the railroads, there lies another Canada little known, unvisited except by the few who are willing to submit to the hardships, loneliness, and toil of long journeys in a land where civilization has left no mark and opened no trails, and where there are no means of subsistence other than those provided by Nature.

Large areas of this section are barren of game, no small consideration to the adventurer caught by the exigencies of travel, for an extended period, in such a district. The greater part, however, is a veritable sportsman's paradise, untouched except by the passing hunter, or explorer; those hardy spirits for whom no privation is too severe, and no labour so arduous as to prevent them from assuaging the wanderlust that grips them and drives them out into the remaining waste places, where the devastating axe has not yet commenced its deadly work, out beyond the Height of Land, over the Great Divide.

This "Backbone of Canada" so called, sometimes known as the Haute Terre, stretches across the full breadth of the continent, East and West, dividing the waters that run south from those that run north to the Arctic Sea. In like manner it forms a line of demarcation between the prosaic realities of a land of everyday affairs, and the enchantment of a realm of high adventure, unconquered, almost unknown, and unpeopled except by a few scattered bands of Indians and wandering trappers.

This hinterland yet remains a virgin wilderness lying spread out over half a continent; a dark, forbidding panorama of continuous forest, with here and there a glistening lake set like a splash of quicksilver amongst the tumbled hills. A harsher, sterner land, this, than the smiling Southland; where manhood and experience are put to the supreme test, where the age-old law of the survival of the fittest holds sway, and where strength without cunning is of no avail. A region of illimitable distance, unknown lakes, hidden rivers, and unrecorded happenings; and changed in no marked way since the white man discovered America.

Here, even in these modern days, lies a land of Romance, gripping the imagination with its immensity, its boundless possibilities and its magic of untried adventure. Thus it has lain since the world was young, enveloped in a mystery beyond understanding, and immersed in silence, absolute, unbroken, and all-embracing; a silence intensified rather than relieved by the muted whisperings of occasional light forest airs in the tree-tops far overhead.

Should the traveller in these solitudes happen to arrive at the edge of one of those high granite cliffs common to the country and look around him, he will see, not the familiar deciduous trees of the south, but will find that he is surrounded, hemmed in on all sides, by apparently endless black forests of spruce, stately trees, cathedral-like with their tall spires above, and their gloomy aisles below. He will see them as far as the eye can reach, covering hill, valley, and ridge, spreading in a green carpet over the face of the earth. Paraded in mass formation, standing stiffly, yet gracefully, to attention, and opposing a wellnigh impenetrable barrier to the further encroachments of civilization, until they too shall fall before the axe, a burnt-offering on the altar of the God of Mammon.

In places this mighty close-packed host divides to sweep in huge undulating waves along the borders of vast inland seas, the far shores of which show only as a thin, dark line shimmering and dancing in the summer heat. These large lakes on the Northern watershed are shallow for the most part, and on that account dangerous to navigate. But in spots are deep holes, places where cliffs hundreds of feet high run sheer down to the water's edge, and on to unfathomed depths below. Riven from the lofty crags by the frosts of centuries, fallen rocks, some of them of stupendous size, lie on some submerged ledge like piles of broken masonry, faintly visible in the clear water, far below. And from out the dark fissures and shadowy caverns among them, slide long, grey, monstrous forms; for here is the home of the great lake trout of the region, taken sometimes as high as forty pounds in weight.

And where the figure of a man is dwarfed by the

majesty and the immensity of his surroundings.

In places long low stretches of flat rock reach up out of the water, entering the wall of forest at a gentle incline. Their smooth surface is studded with a scattered growth of jackpines, fashioned into weird shapes by the wind, and, because standing apart, wide and spreading of limb, affording a grateful shade after long heats at the paddle on the glaring expanse of lake. These are the summer camping grounds of the floating caravans, and off these points a man may catch enough fish for a meal in the time it takes another to make the preparations to cook them.

In the spring time, in sheltered bays, lean and sinuous pike of inordinate size, hungry-looking and rapacious, lie like submarines awash, basking in the sunlight. Shooting them at this season is exciting sport, as only the large ones have this habit, and fish up to fifty inches in length are common.

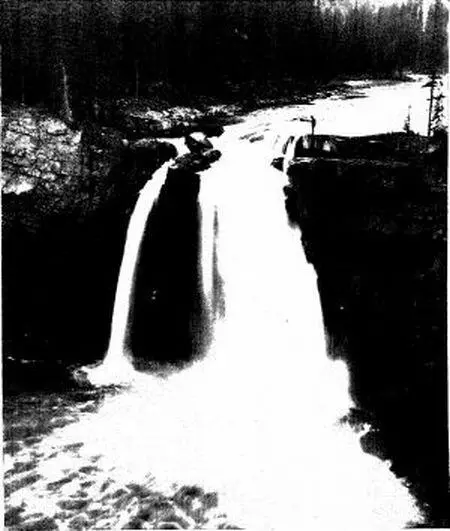

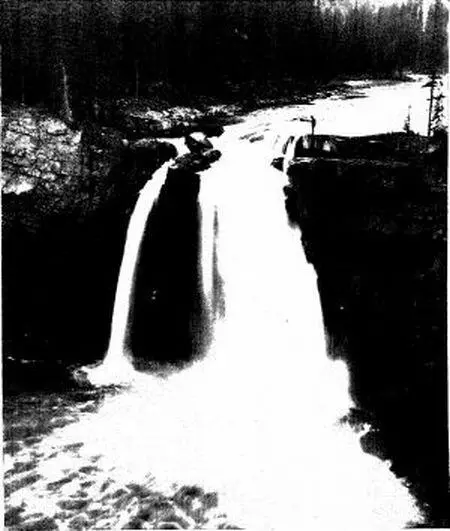

Here and there, too, the sable carpet of evergreen tree-tops is gashed by long shining ribbons of white, as mighty rivers tumble and roar their way to Hudson's Bay, walled in on either side by their palisades of spruce trees, whose lofty arches give back the clatter of rapids or echo to the thunder of the falls.

Far beneath the steeple tops, below the fanlike layers of interlaced limbs that form a vaulted roof through which the sunlight never penetrates, lies a land of shadows. Darkened aisles and corridors lead on to nowhere. A gloomy labyrinth of smooth, grey columns stretches in every direction into the dimness until the view is shut off by the wall of trees that seems to forbid the further progress of the intruder. This barrier opens up before him, as he goes forward, but closes down behind him as though, having committed himself to advance he may not now retire; it hems him in on either side at a given distance as he proceeds, a mute, but ever-present escort. Here, in the endless mazes of these halls of silence, is neither time nor distance, nor direction.

Читать дальше