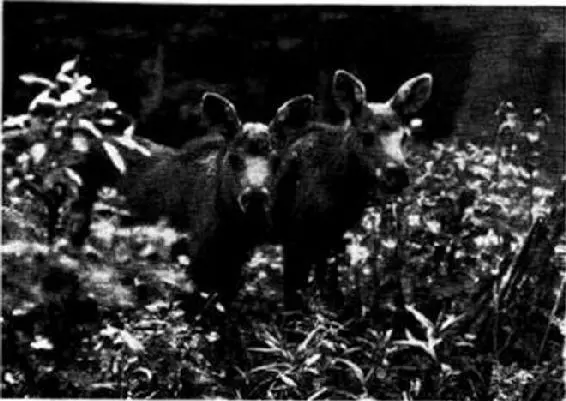

Their mother lost in a forest fire, these two young

Moose came out of the woods to a ranger's cabin.

It is a time of painted forests decked out in all the gay panoply of Indian Summer, of blue haze which lends enchantment to distant prospects, and of hills robed in flaring tints, which, in spite of their brilliance, merge and blend to form the inimitable colour scheme which, once every year, heralds the sad but wondrous spectacle of the falling of the leaves. Motionless days of landscapes bathed in waiting silence; the composed and breathing calm of an immense congregation attending the passing of a beloved one, waiting reverently until the last rites have been completed; for this is the farewell of the leaves to the forest which they have for a time adorned. Their task performed, with brave colours flying they go down in obedience to the immutable law of forest life, later to nourish the parent stem that gave them birth. And in the settled hush that precedes their passing, even the march of time itself seems halted, that there may be no unseemly haste in their disposal, whose life has been so short.

In the endless spruce forests of the High North, much of the beauty of Fall is lost, and passing suddenly out of the gloomy evergreens onto a rare ridge of birch and poplar, with their copper and bronze effects, is like stepping out of a cave into a capacious, many-pillared antechamber draped in cloth of gold. It is only in the hardwood forests of beech, maple and giant black birch yet remaining in certain areas, that the full beauty of the Fall of the Leaf can be appreciated. It was once my fortune to make a trip at this season, in a reserved area of some three thousand square miles in extent, in the heart of the strong woods country, below the Ottawa River. A lovely region it was, and is, of peaceful, rock-girdled lakes, deep, clear, and teeming with trout; and of rich forests of immense trees reaching in a smooth billowing tide in every direction. Here was not the horrific sepulchral gloom of the goblin-haunted spruce country, nor the crowded formation of hostile array. The trees, huge of trunk and massive of high-flung limb, stood decorously apart, affording passage for several men abreast; and the dimness was rather that of some enchanted palace seen only in a dream, and in which chords of stately music could be expected to resound at any moment.

The wide and spreading tops met overhead to form a leafy canopy that was a blaze of prismatic colour, as though the lofty pillars supported a roof of stained glass, through which the sunlight filtered here and there, shedding a dim but mellow glow upon the forest floor.

Between the well-ordered files one walked without obstruction, and in momentary expectation of a fleeting view of some living creature, of the many who dwelt herein. Every step opened up new vistas through the open woodland, the level bottom of which was relieved by terraces edged with small firs that loomed up blackly in the riot of colour, and occasional smooth white boulders which stood crowned by grey and hoary beeches with gnarled limbs, and serpentine, protruding roots, standing like effigies or statues carved from blocks of marble in some old castle garden. There the figure of a man was belittled, dwarfed to insignificant proportions, by the grandeur, and the vast and looming bulk of the objects by which he was surrounded.

At intervals the dimness was brightened, at about twice the height of a man, by the bright tinted foliage of dog-wood, and moose-maple saplings. The gloom made the stems invisible at a little distance, and where the shafts of sunlight struck them, these gay clusters appeared like Japanese lanterns of every imaginable shape and hue, suspended in mid-air to light these ancient halls for some carnival or revel. In the wider spaces between the smooth grey hardwoods, stood the bodies of huge white pine, fluted red-brown columns upwards of six feet across, rearing their bulk up through the roof of leaves, to be shut off completely from further view; yet raising their gigantic proportions another half a hundred feet above the sea of forest, to the great plumed heads that bowed to the eastward each and every one, as though each morning they would salute the rising sun.

Although in the dimness of the ancient forest no breeze stirred the leaves of the young maples, far above, the air was never still. And through the dark masses of the noble sweeping tops of the pine trees, a steady wind played in a deep, prolonged and wavering note, as of the plucked strings of an unseen distant harp; gently humming like the low notes of an organ played softly, dying away to a whisper; swelling again in diapason through the vast transept of the temple of silence, the unceasing waves of sound echoing and resounding across the immeasurable sweep of the universe.

No moose were to be seen in this region, but every once in so often, a group of deer leaped out of sight, with sharp whistles, and spectacular display of white tails.

The air was filled with the low sound of falling leaves, as they made their hesitant way to earth, adding little by little to a variegated carpet already ankle deep. And as they came spinning, floating, and spiralling down like golden snowflakes, the sound of their continuous, subdued, rustling transformed the stately forest into a shadowed whispering gallery, in which it seemed as though the ancient trees would tell in muted accents the age-old secrets of days gone by, did one but have the ears to understand.

To the forest dwellers, autumn, with its sights, its sounds, its smells, its tang, which like good wine, sends the blood coursing and tingling through the veins, with its urge to be up and doing, and the zest and savour of its brittle air, is more than a season; it has become a national institution.

The signs of its coming are eagerly noted by all in whom one drop yet remains of the blood of long gone savage ancestors. Over the whole of North America the first frosts, where they occur, are a signal for the overhauling of weapons of all kinds, and the assembling of implements of the chase. Men step lighter, as with kindling eye they seem to emulate the hustle, the bustle, and the preparation of all living creatures in response to the stirring call of this magic season. For now the Hunting Winds are loosed to course at will along the highways of the forest, stirring the indolent to action, and quickening the impulses with their heady bouquet.

Now the Four-Way Lodge is open, and out from its portals pour the spirits of all the mighty hunters of the Long Forgotten Days, to range again the ancient hunting-grounds. And when a chill wisp of a breeze sweeps down into the forest, and scooping up a handful of leaves, spins them around for a moment in a madly whirling eddy, and of a sudden lets them drop, many will say that it is the shade of some departed hunter who dances a ghostly measure to the tune of the hunting winds.

The woods are full of crisp rustlings, as small beasts scamper over frosted, crackling leaves, intent on the completion of self-appointed tasks. The surface of the waters is broken by clusters of ducks and waterfowl of all kinds, noisily congregated for the fall migration. Along the shore-line, ever-widening V's forge silently ahead, as beaver and muskrats, alert, ready to sink soundlessly out of sight on the least alarm, conduct their various operations. Porcupines amble along trustfully in the open, regardless of danger; and, partly owing to their bristling armour and greatly owing to the luck of fools, generally escape unscathed. Back in the hills any number of bears are breaking off boughs and shredding birch-bark, to line dens that a man could be well satisfied to sleep in.

Читать дальше