At last, piles of bags and boxes lying in scattered heaps, but without confusion; the end, no doubt. You unload, and look around, and see no lake; only a continuation of that never-to-be-sufficiently-damned trail. This, then, is not the end, only a stage. How many more? True to the code you will not ask, but take what comes and like it; you coil your line and return. After all it was worth carrying that jag if only to experience the feeling of comfort walking back without it. You step aside at intervals for heavily laden men; some of them have four hundred pounds and over. Incredible, but there are the bags—count them; a hundred of flour in each. These men trot, with short, choppy steps, but smoothly, evenly, without jar, whilst breath whistles through distended nostrils, and eyes devoid of expression stare glassily at the footing.

Several trips like this, then the canoes are taken. These, carried one to a man, do not stop at the stage, but, an easier load, seventy pounds perhaps, go on to the next stop, so that precious privilege, the rest walking back, will not be forfeited. Otherwise a stoppage would be necessary at the dump before again picking up a load, and delays are neither tolerated, nor expected; the sooner it is over the better; resting merely prolongs the agony. Stage after stage; stifling heat in a breathless scorching tunnel. Our hopes of a short portage have long ago faded entirely. Where is the end of this thing? Maybe there is no end.

And eventually every last piece and pound is dumped on the shores of a lake. Weary men make fire, cook, and wash the brassy film from their throats with hot tea. Hot tea on a broiling day!—yet the system calls for it. The lake is very small; not much respite here; load up, unload, and pack across again.

A new hand asks how many portages there are, and we hear it said that on this first leg of the journey there are fifteen more, and that the next one is called "Brandy" and admitted to be a bad one. We subsequently find this admission to be correct, but at the time, in view of our experiences on the last portage, we are all agog with interest as to what special features this alcoholic jaunt has in store.

We are not long in finding out. Almost a mile in length with five sharp grades arranged without regard for staging or symmetry, it has also a steep slope at the far end, which, being equal in sum to the aggregate of the hills so painfully climbed, at one fell swoop kicks your gains from beneath your feet, and lands you panting and half-dead back at the same level from which you started. So this is Brandy. She is, as we heard, a man-killer; and well named, for it is quite conceivable that more than one stricken man has found himself compelled to reach for his flask, before finally vanquishing this monster.

On the way back, after the first trip, we see the new man. He sits on a log with his head in his hands, exhausted, dejected. He can go no further. The Trail, ever on the watch, has weighed him in the balance, and he is found wanting. He will be sent back; for this is the Trail, where none may falter or linger, or evade the issue. For the time being he must do what he can, as to leave him is out of the question, but the weeding-out process has commenced.

On the third day we enter the pineries. Hills black with pine to the water's edge. Rock walls hundreds of feet in height and crowned with pine, falling sheer down into deep water. Pine, in mass formation, standing solemn, dignified, kings of all the forest; a sea of black sweeping tops swinging to the North; myriads of dark arms pointing one way, Northward, to journey's end; as though in prophetic spirit they see their doom approaching, and would flee before it to the last stronghold of the Red Gods. We are now entering the area for which this corps will be held responsible till late Fall, and two canoe crews receive their instructions, and leave the brigade, taking each their separate way to a designated patrol district.

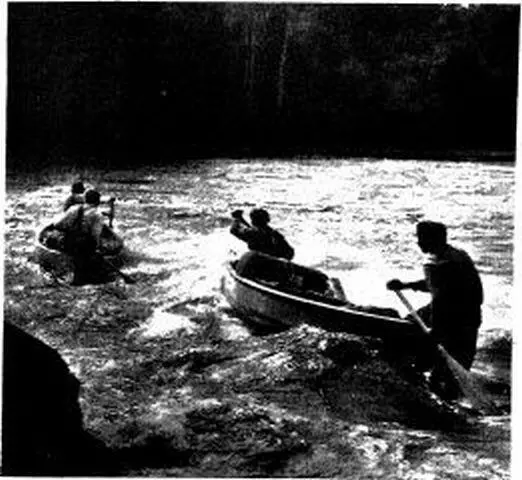

And as the canoes careen and sidle they plunge their way to

safety out into the pool below with its dark ring of silent trees.

Indian signs now become frequent; teepee poles amongst the pine trees, in the glades, and on the beaches; caches raised high on scaffolds in sheltered spots; trail signs, marking a route; shoulder bones of moose hanging in pairs at camp grounds; bear skulls grinning out over the lake from prominent points. If you are stuck for tobacco you will find some in the empty brain box; but no bushman will take it; reprisals for vandalism of that kind may entail endless trouble. I once heard a white guide severely reprove a half-breed belonging to his party, who, wishing to show contempt for such customs, and considering himself above them, took one of these skulls down and commenced to fill his pipe from it. The guide gave in no uncertain terms his opinion of the unsportsmanlike proceeding.

This is an Indian country; and at evening the double staccato beat of a drum swells and ebbs through the still air, faint but very clear, yet unaccountably indeterminate as to direction. A strangely stirring sound, giving an eerie quality to the surroundings. Those pines heard that sound three hundred years ago, when they were saplings; beneath these very trees the Iroquois war parties planned their devilish work, to a similar rhythm. We had thought these things were no longer done. The Cree is questioned, but he blinks owlishly, and has suddenly forgotten his English. The following day shows no sign of living Indians, but here and there is a grave with its birch-bark covering, and personal effects; always in a grove of red pines, and facing towards the sunset. Moose are seen every day now, and two men told off to fish when the evening halt is made, generally return in half an hour, or less, with enough fish for the entire party's meal.

Immense bodies of water many miles in length alternate with carries of from a hundred yards to three miles, so that there are stretches where we pray for a portage, and portages where we pray for a stretch. The pine-clad mountains begin to close in on the route, the water deepens, narrows, and commences to flow steadily.

We are now on the head of a mighty river, which drains all this region, and soon the portages become shorter, but more precipitous, and are flanked on one side or the other by a wicked rapids. Some of these can be run; but not all are experts, and the Chief will not allow valuable cargoes and, perhaps, useful lives to be sacrificed in order that some man of uncertain ability may try to qualify as a canoeman. Rocks that would rip the bottom from a canoe at a touch, lie in wait, invisible, just below the surface, but indications of their position are apparent only to the practised eye. Eddies, that would engulf a pine tree, tug at the frail canoe essaying to drag it into the vortex. Treacherous cross-currents snatch viciously at the paddles; deceptive, smooth-looking, oily stretches break suddenly into six-foot pitches.

But there are amongst us some who have earned the right to follow their own judgment in such matters; these now take control of the situation. They are the "white water men," to whom the thunderous roar of a rapids, and the smell of spray flying in the face, are as the intoxication of strong drink. To such as these considerations of life and limb loom small compared with the maddening thrill of eluding and conquering the frenzied clawing and grasping of tons of hungry, rushing waters; yet coupled with this stern joy of battle is a skill and a professional pride that counts the wetting of a load, or the taking of too much water, an ineradicable disgrace.

Читать дальше