From 2016 onwards, several financial institutions introduced a ‘formal’ RAF for non-financial risks. Still, most companies started approaching non-financial risks with broad qualitative statements, while only the most advanced institutions adopted a ‘business steering’ approach, with quantitative metrics cascaded into business operational limits, making explicit the trade-offs between business decisions and risk exposures. This business-oriented approach has marked an important step forward from the traditional slogan of ‘zero tolerance’ to a practical risk-based decision-making tool, which in the most advanced institutions is closely interlinked with other key business processes (e.g. strategic planning).

Nonetheless, the sophistication of quantitative indicators and level of granularity are not homogeneous across non-financial risk types. For some, it has proven convenient and feasible to transform a qualitative, high-level statement into quantitative metrics, to then further break them down into detailed indicators. In other cases, however, quantitative metrics are absent or still limited, and the RAF has remained mainly a qualitative exercise. This chapter will illustrate different ways adopted by market players to embed non-financial risks in RAFs.

The core concepts underlying a RAF, unanimously recognised by regulators and transversely applied for financial as well as non-financial risks, are “appetite,” “capacity” and “limit.” [7]These express how risk is measured and the relevant thresholds are monitored:

Risk Appetite is intended as the express, formal statement concerning the aggregate type and levels of risks which an entity is willing to accept in its effort to pursue its strategic objectives. It can be expressed either as a quantitative measure or as a qualitative sentence. When detailed at a metric/indicator level, it is often identified as “target” and provides the reference threshold for the business’ development and steering, indicating the risk level considered optimal for the organisation.

Risk Capacity (sometimes also referred to as “limit”) is intended as the maximum level of risk that can be tolerated by the entity, before breaching relevant constraints (either regulatory or internal). Values beyond it are considered unacceptable, and both management and the board must take this into consideration when taking risk decisions in normal as well as in stressed conditions.

Risk targets/caution/limit levels are the quantitative thresholds which cascade the aggregate risk appetite at the operational level (business line, entity). They represent the maximum acceptable deviation from the target level, and they are set leaving sufficient room to operate, also in stress conditions.

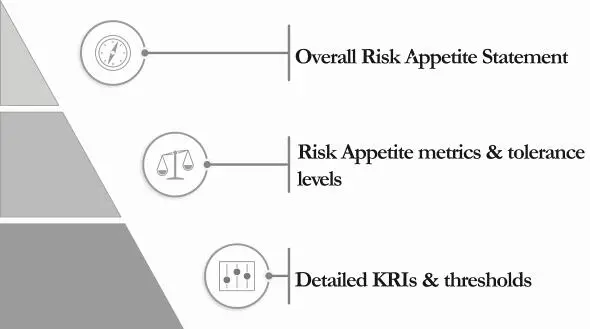

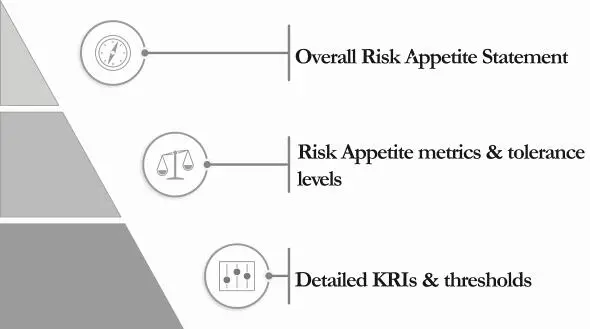

Considering the definitions above, market players typically define three different levelswithin their RAFs:

Level 1: Overall risk appetite statement (RAS)

A high-level formal declaration that sets out the types and level of risks that can be assumed in the pursuit of strategic business objectives, for each risk type. For the RAS to be actionable, it usually contains express indication of:

key principles guiding response to non-financial risks, to be cascaded in risk appetite metrics;

prohibited activities for the organisation for which “zero tolerance” applies.

Level 2: Risk appetite metrics and tolerance levels

Primary metrics in which the overall RAS can be disaggregated and the related tolerance thresholds set. Usually linked to residual risk measures captured by a risk assessment, this is the primary step to allow measurement and monitoring of the entity’s performance against applicable risk appetite objectives and limits.

Level 3: Detailed risk indicators and thresholds

Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) that allow the institution to measure and monitor the performance of the defined risk appetite metrics, and allow for a definition of detailed tolerance thresholds (target, caution, limit) for each. The further disaggregation of risk appetite metrics into KRIs can simplify continuous monitoring and the implementation of remediating actions to decrease levels of risk if necessary.

An RAF’s design and parametrisation involves all three lines of defence. [8]Given the strategic purpose of RAF, embedding business evaluation is critical to make RAF a steering tool for the organisation. The most mature market players involve key business functions across all the three levels of the framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Three levels in risk appetite frameworks

3.2 RAF Level 1: Overall Risk Appetite Statement

The first level is aimed at setting high-level principles driving risk appetite, and it is organised across two building blocks: overall statement and prohibited activities.

The overall statement outlines all levels and types of risk that the bank is willing to take on for each risk type within its risk capacity to achieve its strategic objectives and business plan. The statement, especially for non-financial risks, plays a pivotal role, thus, it should be sufficiently structured and specific to provide guidance and actionable implications for risk management decisions.

As general good practice, the following four RAF elements should be addressed in each statement:

definition of the entity’s ambition towards regulatory compliance (e.g. compliance to minimum applicable requirements versus full compliance also to non-mandatory requirements);

translation of the ambition into objectives, expressed for example in terms of internal operations and customer interactions;

expression of tracking mechanisms by which it is possible to acknowledge progress towards the objective;

identification of the standards by which the bank measures its performance.

The table below shows exemplary non-financial risk RAF statements from large international banks.

Table 1:Examples of risk appetite statements for non-financial risks (focus: compliance risks)

| 1 – Large international banking group“The Group is firmly committed to complying with all applicable sanctions regulations in every jurisdiction in which it operates; it may also decide to introduce further restrictions on business activities involving certain countries, organisations, persons, entities or goods, irrespective of whether they are the subject of a particular sanction imposed by a country or international organisation. The Group requires all employees to be vigilant in identifying any business activity that potentially involves a sanctioned country, organisation, person, entity or good.” 2 – Turkish commercial bank“The Bank’s Risk Committee is responsible for the board complying with formal regulatory rules and laws in order to avoid sanctions and legal fines. The members of the Risk Committee aim to collectively monitor and report compliance related sanctions and losses, and it takes corrective actions together with the regulatory and supervisory authorities.” 3 – Italian commercial bank“The Group considers compliance with the regulations and fairness in business to be fundamental to the conduct of banking operations, which by nature is founded on trust. The Group aims for formal and substantive compliance with rules in order to avoid penalties and maintain a solid relationship of trust with all of its stakeholders; in this regard, it aims to minimise the potential impact of negative events that jeopardise the Group’s economic stability and image.” 4 – Large international banking group“The Bank is committed to complying to all applicable regulation and legislation throughout its operations, and to cooperating with authorities in order to identify, prevent and eliminate activities, practices and behaviours leading to violations. The Bank continuously monitors its compliance performance and initiates remedial action as required according to the standards set on the country’s, the European and an international level.” |

Considering example 4, the statement can be translated into concrete guidelines on risk tolerance, since it conveys the message that escalation must be triggered whenever non-compliance to applicable regulatory requirements is detected. In turn, such a provision can be transformed into actionable indications concerning metrics to be measured and their according escalation paths. As an example, it can be defined that if a risk category reaches a high-risk level, it will be escalated to the board, while risk categories reaching a medium risk level will be escalated to the respective nominated person, such as the chief compliance officer (CCO) or the head of operational risk.

Читать дальше