Surya K. De - Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Surya K. De - Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The professional guide to cancer diagnosis and therapy for researchers and clinicians Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention,

Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention

Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Tobacco smoke from cigarettes, however, is a much more significant source of exposure to acrylamide than food.

In studies using rodent models, acrylamide exposure was linked to an increased risk of developing several types of cancer [107–117]. According to the National Toxicology Program's Report on Carcinogens, acrylamide is likely carcinogenic based on its effect in laboratory animals given drinking water contaminated with this compound. More studies, however, need to be done to find out the levels and length of exposure required to affect humans.

Certain occupations involve more employee contact with cancer‐causing substances. Some workers are exposed daily. A few occupations at higher risk include aluminum workers, painters, tar pavers (who are exposed to carcinogenic benzene), rubber and plastic manufacturers, hairdressers, and manicurists in nail salons.

2.14 Possible Human Carcinogens

A carcinogen is any substance that promotes carcinogenesis, the formation of cancer. An English physician John Hill first observed in 1761 that certain chemical exposures have been linked to the development of cancer [118]. He noted that the snuff users developed nasal cancer more frequently than the general population. Over 100 000 chemicals are used, and about 1000 new chemicals are listed each year, but not all chemicals are carcinogens. These chemicals are found in everyday items, including as foods, personal products, packaging, prescription drugs, and household and lawn care products [119–122]. While some chemicals may be harmful, not all contact with chemicals is dangerous to your health. Examples of known human carcinogens are asbestos, arsenic, benzene, beryllium, cadmium, nickel, vinyl halides, and others. Examples of possible human carcinogens are chloroform, DDT, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, aromatic amines, azo dyes, nitrosamines and nitrosamides, hydrazo and azoxy compounds, carbamates, halogenated compounds, natural products, and others. DNA bases such as purine and pyrimidine are nucleophiles and react with any electrophiles resulting in DNA damage. Some reactive chemicals such as alkylating agents (alkyl halides), aldehydes, and others directly make a covalent bond with nucleophilic sites in the purine and pyrimidine rings of nucleic acids. Some chemicals react with DNA after being metabolized by the liver cytochrome P450 enzymes. For example, some alkenes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are metabolized by human liver enzymes to produce an electrophilic epoxide. DNA attacks the epoxide and is bound permanently to it and damages normal cells.

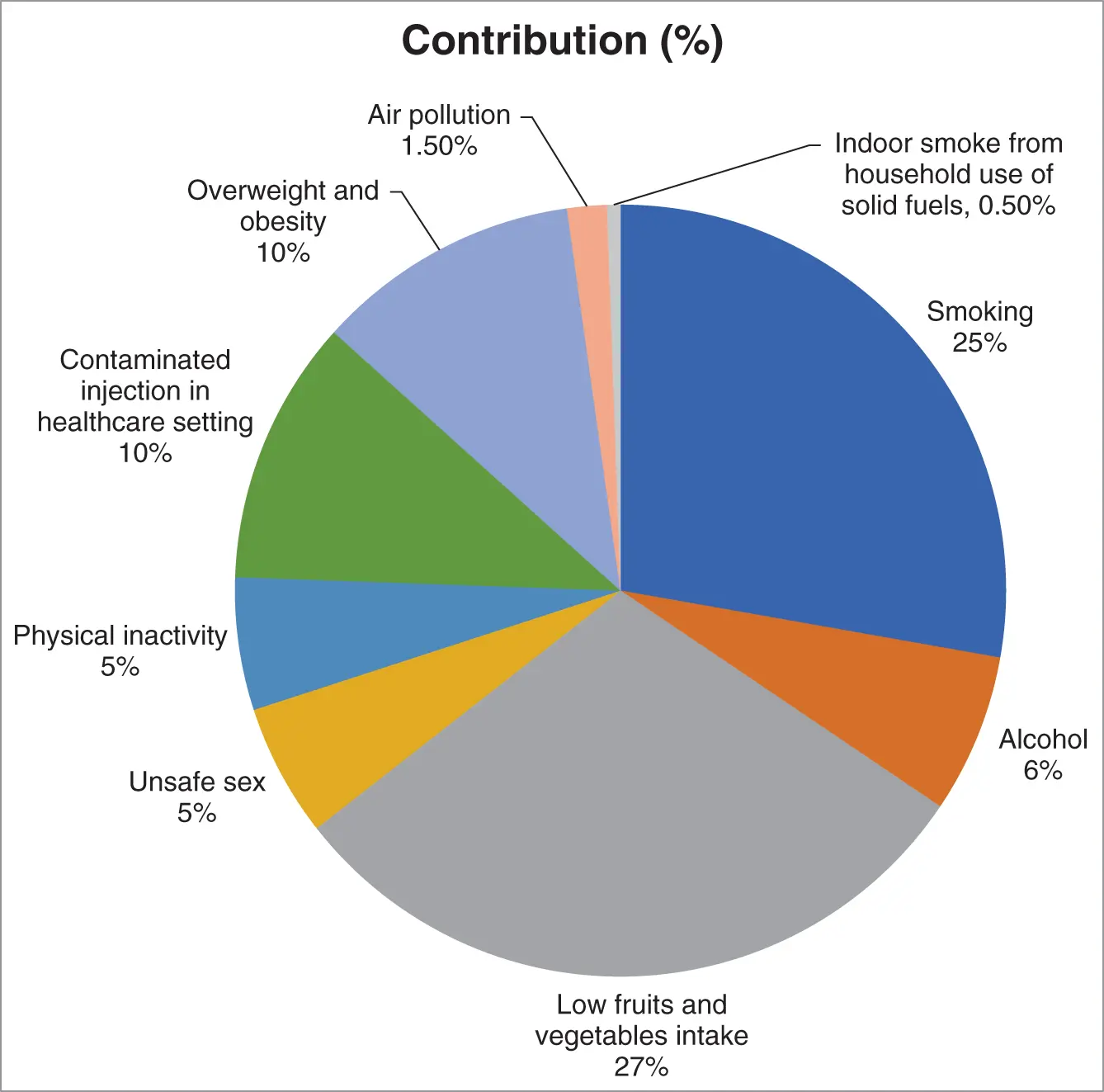

An estimation of some factors contributing to cancer development and their relative significance is shown in ( Figure 2.19).

2.15 Guidelines for Early Detection of Cancer

The following are the current American Cancer Society guidelines for early detection of cancer in most men and women:

Figure 2.19 Factors contributing to cancer development and their relative significance.

| Women aged 20–29: | Breast exam and Pap test (for cervical cancer) every 1–3 yr. |

| Women aged 30–39: | Mammograms (X‐rays of the breast) every 1–3 yr, Pap test and HVP test every 5 yr. |

| Women aged 40–49: | Breast test every year, Pap and HPV test every 5 yr. |

| Women aged 50–75: | Mammograms every year, Pap and HPV test every 5 yr, colonoscopy every 10 yr, colon CT scan every 5 yr. a) |

| Women aged 76+: | Your doctor will decide. |

| Men aged above 50: | Prostate cancer test and colonoscopy every 10 yr. |

| All adults aged 50–75: | If smoking, testing for lung cancer every year; if not smoking and in good health, testing for lung cancer every 10 yr. |

a)Women at the time of menopause should consider testing for endometrial cancer. Any unexpected vaginal bleeding or spotting should be reported to a physician immediately.

References

1 1 Rossouw, J.E., Anderson, G.L., Prentice, R.L. et al. (2002). Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288 (3): 321–333.

2 2 Anderson, G.L., Limacher, M., Assaf, A.R. et al. (2004). Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291 (14): 1701–1712.

3 3 LaCroix, A.Z., Chlebowski, R.T., Manson, J.E. et al. (2011). Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 305 (13): 1305–1314.

4 4 Chlebowski, R.T., Anderson, G., Pettinger, M. et al. (2008). Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer detection by means of mammography and breast biopsy. Archives of Internal Medicine 168 (4): 370–377.

5 5 Chlebowski, R.T., Kuller, L.H., Prentice, R.L. et al. (2009). Breast cancer after use of estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women. New England Journal of Medicine 360 (6): 573–587.

6 6 Chlebowski, R.T., Schwartz, A.G., Wakelee, H. et al. (2009). Estrogen plus progestin and lung cancer in postmenopausal women (Women's Health Initiative trial): a post‐hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374 (9697): 1243–1251.

7 7 Crandall, C.J., Hovey, K.M., Andrews, C.A. et al. (2018). Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause 25 (1): 11–20.

8 8 Holmberg, L. and Anderson, H. (2004). HABITS (hormonal replacement therapy after breast cancer – is it safe?), a randomised comparison: trial stopped. Lancet 363 (9407): 453–455.

9 9 Pachman, D.R., Jones, J.M., and Loprinzi, C.L. (2010). Management of menopause‐associated vasomotor symptoms: current treatment options, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Women's Health 2: 123–135.

10 10 Franco, O.H., Chowdhury, R., Troup, J. et al. (2016). Use of plant‐based therapies and menopausal symptoms: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA 315 (23): 2554–2563.

11 11 Flegal, K.M., Kruszon‐Moran, D., Carroll, M.D. et al. (2016). Trends in obesity among adults in the United States. JAMA 315 (21): 2284–2291.

12 12 Kushi, L.H., Doyle, C., McCullough, M. et al. (2012). American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 62 (1): 30–67. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20140. PMID: 22237782.

13 13 Bleyer, A. (2007). Young adult oncology: the patients and their survival challenges. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 57: 242–255.

14 14 Lam, J.U., Rebolj, M., Dugué, P.A. et al. (2014). Condom use in prevention of Human Papillomavirus infections and cervical neoplasia: systematic review of longitudinal studies. Journal of Medical Screening 21 (1): 38–50.

15 15 Winer, R.L., Hughes, J.P., Feng, Q. et al. (2006). Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. The New England Journal of Medicine 354: 2645–2654.

16 16 Hales, C.M., Fryar, C.D., Carroll, M.D. et al. (2018). Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007–2008 to 2015–2016. JAMA 319 (16): 1723–1725.

17 17 Thomson, C.A., McCullough, M.L., Wertheim, B.C. et al. (2014). Nutrition and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines, cancer risk, and mortality in the women's health initiative. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa.) 1: 42–53.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Fundamentals of Cancer Detection, Treatment, and Prevention» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.