ANSES (2018). Avis et rapport de l’Anses relatif à l’attribution des sources des maladies infectieuses d’origine alimentaire. Partie 2 : Analyse des données épidémiologiques. Report [Online]. Available at: https://www.anses.fr/fr/system/files/BIORISK2015SA0162Ra-2.pdf.

Camel, V., Rivière, G., Le Bizec, B. (2018). Risques chimiques liés aux aliments : principes et applications. Lavoisier, Paris.

Codex Alimentarius Commission (1999). Principles and guidelines for the conduct of microbiological risk assessment. CAC/GL 30-1999.

FAO (2020). Microbiological risks and JEMRA [Online]. Available at: http://www.fao.org/food/food-safety-quality/scientific-advice/jemra/en/[Accessed 10 February 2020].

FAO and WHO (2006). Food safety risk analysis: A guide for national food safety authorities [Online]. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-a0822e.pdf. [Accessed November 2021].

FAO and WHO (2020). Public consultation for draft guidance of microbiological risk assessment for food [Online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/public-consultation-for-draft-guidance-of-microbiological-risk-assessment-for-food[Accessed 15 June 2020].

Haddad, N. (2022). Hazards in the Food Processing and Distribution Chain . ISTE Ltd, London and Wiley, New York.

WHO (2015). WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases. Foodborne Diseases Burden Epidemiology Reference Group [Online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/foodbome_disease/fergreport/en/[Accessed January 2021].

WHO (2017). The burden of foodborne diseases in the WHO European Region [Online]. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/402989/50607-WHO-Food-Safety-publicationV4_Web.pdf.

PART 1 Hazards and Food

1

Biological Hazard Identification

Jeanne-Marie MEMBRÉ and Nabila HADDAD

SECALIM, INRAE, Oniris, Nantes, France

Contamination of food with microbial agents is a global public health problem. Microbial hazards in food include bacteria such as Salmonella , viruses such as norovirus, parasites such as trematodes and also prions. Diarrheal diseases are the most common diseases resulting from the consumption of contaminated food and are the cause of 550 million illnesses and 230,000 deaths each year (WHO 2020). Hazard identification serves to establish whether the hazard is probable or actual in the food product and to document important known information about the relationships and interactions between the hazard, the food and the host, and also their relationship to human disease. Given that a wide range of microbiological hazards can cause foodborne illness, hazard identification should determine whether a potential hazard is realistic for the food product concerned (FAO and WHO 2020).

Epidemiological data from disease surveillance programs or investigations of food-borne outbreaks are often the first clearly documented indications of a food safety issue associated with a pathogen causing adverse effects. Food contamination surveillance data, along with product and process assessments, can help identify combinations of hazards and foods. Evidence from these sources is usually quantitative (i.e. it includes information on the concentration or number of units of the hazard in the food) and may also provide information that feeds into other stages of microbiological risk assessment, such as exposure assessment and/or establishment of a dose–response relationship. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is increasingly used for the surveillance of foodborne pathogens, the investigation of epidemics and the search for the sources of contamination throughout the food supply chain (Rantsiou et al. 2018).

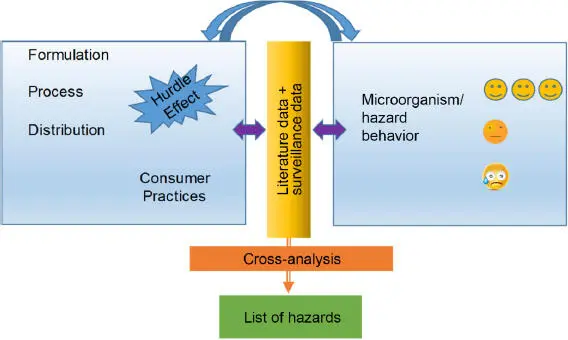

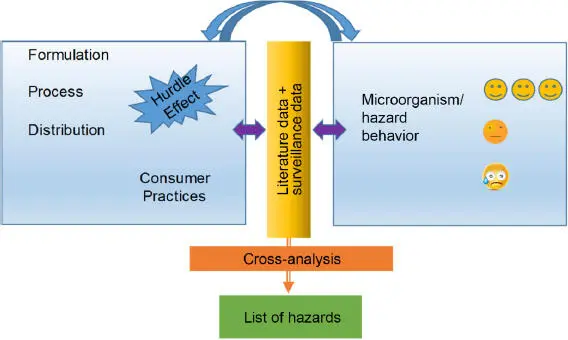

That being said, the epidemiological data must be cross-referenced with product knowledge, in other words its formulation, its process, its distribution channel and the way it is used by the consumer, before conclusions can be drawn on the relevant hazards. Finally, the behavior of the hazard in the food, in other words its ability to multiply, its resistance to stress and its survival, or its inactivation, is the third key element to be taken into account in hazard identification. ( Figure 1.1). We will return later in the chapter to these different types of data and their cross-use.

Figure.1.1. Structuring of information essential to hazard identification. Created with BioRender.com

1.2. Who conducts hazard identification?

Hazard identification is the first stage in risk assessment. It is therefore often carried out by health agencies such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in Europe or ANSES in France when these agencies are seeking to clarify an action or a decision relating to food safety.

However, hazard identification is also implemented by companies, or more precisely by companies’ quality departments, when they are setting up their Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) systems. The HACCP system is a methodology that identifies, assesses and helps control hazards that have significance for food safety (Membré 2014). The HACCP system is a preventive operation, specific to a manufacturing unit, which begins with the purchase of raw materials, ingredients and packaging materials, follows the entire production process and ends at the finished product, ready for consumption. The HACCP system is based on seven principles, the first being “carry out a hazard analysis”. This first principle includes hazard identification. Conducting this identification should be assigned to a highly qualified team with proven skills in food microbiology.

1.3. Sources of useful information for hazard identification

The WHO and the FAO have listed the various types of data that can be used in hazard identification (FAO and WHO 2020), along with their benefits and drawbacks. Their main conclusions are summed up in Table 1.1.

The data cited by the WHO and FAO can be categorized according to their origin (whether they have been obtained from the scientific literature or from surveillance) and nature (epidemiological studies, prevalence and concentrations, early warning, toxi-infection, public health).

Food safety agencies provide professionals in the agrifood sector with factsheets describing biological hazards transmissible through food. These factsheets are updated regularly and are available online; they can also provide useful information for hazard identification. By way of example:

– ANSES’ factsheets are available in French at https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/fiches-de-dangers-biologiques-transmissibles-par-les-aliments;

– Canadian factsheets are available at https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-publique/services/biosecurite-biosurete-laboratoire/fiches-techniques-sante-securite-agents-pathogenes-evaluation-risques.html.

Table 1.1. The various types of data that can be used in hazard identification (FAO and WHO 2020)

| Type of data |

Description |

Benefits |

Drawbacks |

| Literature data: epidemiological studies |

Epidemiological investigations relate to studies that have been commissioned to specifically study the cause and effect relationship between the appearance of foodborne diseases and exposure to certain microbiological risks through the consumption of food. |

Epidemiological studies are very specific and provide a vast amount of detailed information about the hazard and the group of consumers studied. |

The data are often generated for a relatively small number of consumers and therefore are not representative of larger consumer groups. |

| Literature data: prevalence and concentration data |

Studies identifying the prevalence and count/concentration of target microorganisms at various stages of production/distribution and studies identifying their evolution, such as the effectiveness of a transformation procedure. |

These studies are particularly useful for exposure assessment, but can also be used for hazard identification. |

The diversity of detection and/or counting methods makes it difficult to compare final estimates. Internationally validated microbiological methods to facilitate this comparison should be preferred. |

| Surveillance data: early warning systems |

A food-safety early warning system allows national authorities to share information on measures taken in response to serious risks detected in relation to food and can thus provide useful information for hazard identification. The European RASFF system is an example of a food-safety early warning system that provides valuable information on product withdrawals and recalls. |

An early warning system enables the sharing of data between geographically linked parties in an efficient manner. The data are accessible in a digital format, for example, in the Excel file format in RASFF. |

The system is only as good as its least active participant. If one country does not have the resources or the expertise to easily contribute to the data, then the resulting dataset is limited or biased in favor of the other countries in the system. Emerging hazards that are not actively investigated, or that do not need to be reported through a national health system, are less likely to be captured in an early warning system. |

| Surveillance data: collective food toxi-infection data |

Appearance of at least two similar cases of a symptomatology, generally gastrointestinal, the cause of which can be attributed to the same food origin. When an infection occurs, an epidemiological investigation is usually undertaken. |

Obtaining very specific details about the food source and its preparation in the context of the outbreak is often possible, because of the emphasis on a single food or meal. |

There are limitations to using collective food toxi-infection data in preparing dose–response modeling but not really for hazard identification. |

| Surveillance data: public health data |

Countries and several international organizations compile health statistics on infectious/zoonotic diseases. An example of a public health data compilation is Pulsenet. |

The data are often very specific, with fairly detailed descriptions of the food (e.g. type, quantity, composition), the pathogen (reliably identified, often subtyped) and the consumer (e.g. age, sex, state of health). |

These data are highly dependent on the sophistication of the surveillance system used to collect the information.The data relate only to a limited range of microbiological hazards and do not (or only slightly) reflect sporadic cases. |

| Surveillance data: food contamination |

Governments often have proactive food and water sampling programs in place to detect microbiological hazards, which can be expressed as the percentage of contaminated samples (the prevalence) and/or as concentration in the food. In addition, government agencies (inspection and control departments or designated laboratories) carry out routine surveillance monitoring. These data can be useful for hazard identification and also for exposure or risk assessment. |

These activities generate significant amounts of data, in the form of information both on prevalence and on the level of contamination. To permit optimal evaluation of the data on prevalence and level of contamination, the associated meta data should be provided: year, season, geographical location, country, etc. |

It may be that these data are not random or fully representative. They are generated in the framework of official control systems that often take resource limitations into account by targeting foods that are known to be problematic. |

In parallel with composing hazard factsheets, ANSES has begun detailed work on source attribution (ANSES 2017a, 2018), which can also be used as a documentary source for hazard identification. Source attribution involves quantifying the relative share of various sources in the burden of infectious diseases transmitted through food (ANSES 2017a). It seeks to allocate the number of cases of infectious diseases transmitted by food to the various sources. Sources include:

Читать дальше