John Stephens - Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Stephens - Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1838, Жанр: Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1838

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Descending toward the Acropolis, and entering the city among streets encumbered with ruined houses, we came to the Temple of the Winds, a marble octagonal tower, built by Andronicus. On each side is a sculptured figure, clothed in drapery adapted to the wind he represents; and on the top was formerly a Triton with a rod in his hand, pointing to the figure marking the wind. The Triton is gone, and great part of the temple buried under ruins. Part of the interior, however, has been excavated, and probably, before long, the whole will be restored.

East of the foot of the Acropolis, and on the way to Adrian's Gate, we came to the Lantern of Demosthenes (I eschew its new name of the Choragic Monument of Lysichus), where, according to an absurd tradition, the orator shut himself up to study the rhetorical art. It is considered one of the most beautiful monuments of antiquity, and the capitals are most elegant specimens of the Corinthian order refined by Attic taste. It is now in a mutilated condition, and its many repairs make its dilapidation more perceptible. Whether Demosthenes ever lived here or not, it derives an interest from the fact that Lord Byron made it his residence during his visit to Athens. Farther on, and forming part of the modern wall, is the Arch of Adrian, bearing on one side an inscription in Greek, "This is the city of Theseus;" and on the other, "But this is the city of Adrian." On the arrival of Otho a placard was erected, on which was inscribed, "These were the cities of Theseus and Adrian, but now of Otho." Many of the most ancient buildings in Athens have totally disappeared. The Turks destroyed many of them to construct the wall around the city, and even the modern Greeks have not scrupled to build their miserable houses with the plunder of the temples in which their ancestors worshipped.

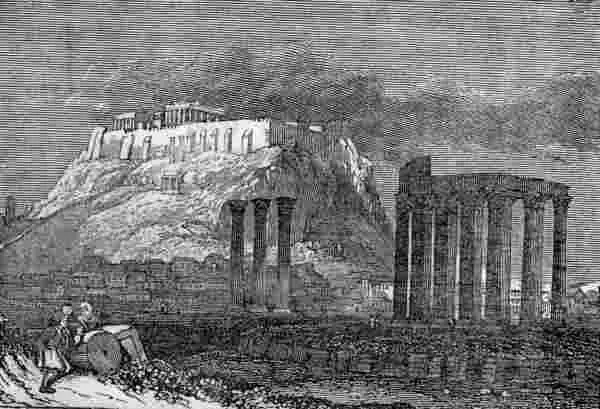

Passing under the Arch of Adrian, outside the gate, on the plain toward the Ilissus, we came to the ruined Temple of Jupiter Olympus, perhaps once the most magnificent in the world. It was built of the purest white marble, having a front of nearly two hundred feet, and more than three hundred and fifty in length, and contained one hundred and twenty columns, sixteen of which are all that now remain; and these, fluted and having rich Corinthian capitals, tower more than sixty feet above the plain, perfect as when they were reared. I visited these ruins often, particularly in the afternoon; they are at all times mournfully beautiful, but I have seldom known anything more touching than, when the sun was setting, to walk over the marble floor, and look up at the lonely columns of this ruined temple. I cannot imagine anything more imposing than it must have been when, with its lofty roof supported by all its columns, it stood at the gate of the city, its doors wide open, inviting the Greeks to worship. That such an edifice should be erected for the worship of a heathen god! On the architrave connecting three of the columns a hermit built his lonely cell, and passed his life in that elevated solitude, accessible only to the crane and the eagle. The hermit is long since dead, but his little habitation still resists the whistling of the wind, and awakens the curiosity of the wondering traveller.

The Temple of Theseus is the last of the principal monuments, but the first which the traveller sees on entering Athens. It was built after the battle of Marathon, and in commemoration of the victory which drove the Persians from the shores of Greece. It is a small but beautiful specimen of the pure Doric, built of Pentelican marble, centuries of exposure to the open air giving it a yellowish tint, which softens the brilliancy of the white. Three Englishmen have been buried within this temple. The first time I visited it a company of Greek recruits, with some negroes among them, was drawn up in front, going through the manual under the direction of a German corporal; and, at the same time, workmen were engaged in fitting it up for the coronation of King Otho!

Temple of Jupiter Olympus and Acropolis at Athena.

These are the principal monuments around the city, and, except the temples at Pæstum, they are more worthy of admiration than all the ruins in Italy; but towering above them in position, and far exceeding them in interest, are the ruins of the Acropolis. I have since wandered among the ruined monuments of Egypt and the desolate city of Petra, but I look back with unabated reverence to the Athenian Acropolis. Every day I had gazed at it from the balcony of my hotel, and from every part of the city and suburbs. Early on my arrival I had obtained the necessary permit, paid a hurried visit, and resolved not to go again until I had examined all the other interesting objects. On the fourth day, with my friend M., I went again. We ascended by a broad road paved with stone. The summit is enclosed by a wall, of which some of the foundation stones, very large, and bearing an appearance of great antiquity, are pointed out as part of the wall built by Themistocles after the battle of Salamis, four hundred and eighty years before Christ. The rest is Venetian and Turkish, falling to decay, and marring the picturesque effect of the ruins from below. The guard examined our permit, and we passed under the gate. A magnificent propylon of the finest white marble, the blocks of the largest size ever laid by human hands, and having a wing of the same material on each side, stands at the entrance. Though broken and ruined, the world contains nothing like it even now. If my first impressions do not deceive me, the proudest portals of Egyptian temples suffer in comparison. Passing this magnificent propylon, and ascending several steps, we reached the Parthenon or ruined Temple of Minerva; an immense white marble skeleton, the noblest monument of architectural genius which the world ever saw. Standing on the steps of this temple, we had around us all that is interesting in association and all that is beautiful in art. We might well forget the capital of King Otho, and go back in imagination to the golden age of Athens. Pericles, with the illustrious throng of Grecian heroes, orators, and sages, had ascended there to worship, and Cicero and the noblest of the Romans had gone there to admire; and probably, if the fashion of modern tourists had existed in their days, we should see their names inscribed with their own hands on its walls. The great temple stands on the very summit of the Acropolis, elevated far above the Propylæa and the surrounding edifices. Its length is two hundred and eight feet, and breadth one hundred and two. At each end were two rows of eight Doric columns, thirty-four feet high and six feet in diameter, and on each side were thirteen more. The whole temple within and without was adorned with the most splendid works of art, by the first sculptors in Greece, and Phidias himself wrought the statue of the goddess, of ivory and gold, twenty-six cubits high, having on the top of her helmet a sphinx, with griffins on each of the sides; on the breast a head of Medusa wrought in ivory, and a figure of Victory about four cubits high, holding a spear in her hand and a shield lying at her feet. Until the latter part of the seventeenth century, this magnificent temple, with all its ornaments, existed entire. During the siege of Athens by the Venetians, the central part was used by the Turks as a magazine; and a bomb, aimed with fatal precision or by a not less fatal chance, reached the magazine, and, with a tremendous explosion, destroyed a great part of the buildings. Subsequently the Turks used it as a quarry, and antiquaries and travellers, foremost among whom is Lord Elgin, have contributed to destroy "what Goth, and Turk, and Time had spared."

Around the Parthenon, and covering the whole summit of the Acropolis, are strewed columns and blocks of polished white marble, the ruins of ancient temples. The remains of the Temples of Erectheus and Minerva Polias are pre-eminent in beauty; the pillars of the latter are the most perfect specimens of the Ionic in existence, and its light and graceful proportions are in elegant contrast with the severe and simple majesty of the Parthenon. The capitals of the columns are wrought and ornamented with a delicacy surpassing anything of which I could have believed marble susceptible. Once I was tempted to knock off a corner and bring it home, as a specimen of the exquisite skill of the Grecian artist, which it would have illustrated better than a volume of description; but I could not do it; it seemed nothing less than sacrilege.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland, Vol. 1 (of 2)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![William Frith - John Leech, His Life and Work. Vol. 1 [of 2]](/books/747171/william-frith-john-leech-his-life-and-work-vol-thumb.webp)

![William Frith - John Leech, His Life and Work, Vol. 2 [of 2]](/books/748201/william-frith-john-leech-his-life-and-work-vol-thumb.webp)