The latter needed all his courage and cunning to escape the eighty thousand Russians who were blocking his way. Ney replied to the general who was ordering him to lay down his weapons that “a marshal of France never gives himself up.” Then he fired his last bullets, made a diversion, returned toward Smolensk, maneuvered in the night, and, after two days of forced march during which they were relentlessly harried by the Cossacks, he managed to cross over the right bank of the Dnieper and reach Orsha. Of the six thousand men who had left Smolensk with him, about a thousand remained. Ney’s new tour de force cheered up the Emperor and, for a few hours, distracted him from the terrible news that Minsk was in enemy hands.

The men marched relentlessly on the track. Inkovno, Krasny, Orsha went by slowly, as monuments to horror. Even the Emperor had to get out of his carriage and walk leaning on the arm of Caulaincourt or a camp aide. The road was cluttered with dead men and horses, dying civilians and soldiers, crates, carts, cannons, and all that the scattering army was losing behind it. Those who were not dead stumbled over the corpses of those who had already fallen. The men advanced through soul-destroying plains. The cold had destroyed all hope, God no longer existed, the temperatures were dropping, and they were still putting one foot in front of the other. Crazy with suffering, emaciated, eaten by vermin, they walked straight on, from fields covered in dead to other fields of graves. Every forced step constituted salvation as well as loss. They walked on and were cursed.

How did these men stand this crazy march? How did some of them survive this fast-paced carousel of death and the frost? Of what metal were they forged, these shako-wearing skeletons who still cheered the man who pretended to pull them out of hell through the same path by which he had brought them there? Napoleon must have radiated a truly magnetic power for his men not to bear a grudge against him for their misfortune and even lose any bitterness as soon as he appeared! Not one soldier would have considered feeling resentment toward the Emperor. How can we, they said, hold something against the one who led us to Egypt, Italy, and Spain, who subjugated the world and made the sovereigns of Europe quake? The one who turned energy, youth, and heroism into the virtues of a reign. Léon Bloy raps out at him in the dynamite-fueled pages of his Napoleon’s Soul : “When these wretches died shouting ‘Long live the Emperor!’ they genuinely believed they were dying for France, and they were not wrong.” And it was like Bloy to be touched by a poor grenadier who finds the strength to go into raptures when the Emperor walks on foot in the midst of ghosts of the Old Guard, “He, so great, who makes us proud.”

Bourgogne was not outdone in his fondness for the chief, but, just over the page, provides another key: “Although we were unhappy, and dying from hunger and the cold, we still had something to support us: honor and courage.” Honor and courage! What a strange ring these words had two hundred years later. Were these words still alive in the world we were crossing with our headlights on full? We made a short pause on the shoulder. It was snowing, and the night seemed to be in tears in the beam of the headlights. Good God, I thought while pissing in the dark, we poor 21st-century guys are such dwarves, aren’t we? Softened in the mangrove of comfort, how could we understand these 1812 ghosts? Could we quiver with the same passion and accept the same sacrifices? Or even understand them? The Glorious Thirties had been useful for this: develop family paradise, domestic bliss, private enjoyment. Allow us to have a lot to lose. Would we be ready to abandon our Capuas to fight the Moujiks beneath the bulbs, or conquer the pyramids?

Moreover, we had become individuals. And, in our world, the individual did not accept sacrifice except for other individuals of his or her choice: his family, his nearest and dearest, perhaps a few friends. The only conceivable wars consisted in defending our property. We were quite happy to fight, but only for the safety of the floor where our apartments were. We would never have competed in enthusiasm at the prospect of sacrificing ourselves for an abstract concept that was superior to us, for the collective interest or—worse—for the love of a chief.

It must be said that the 20th century was over and its hideousness still horrified us. That’s what made us different than the Old Guard. We knew that Verdun and Stalingrad, Buchenwald and Hiroshima were the Fall of Man and we were haunted by that. From now on, the idea of conquest sounded absurd.

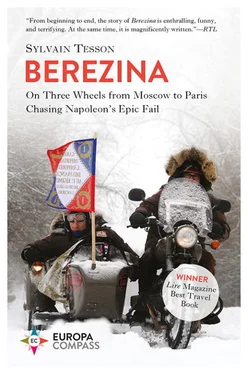

The snowfall got heavier as we approached Barysaw. I couldn’t see anything. The white strip was my Ariadne’s thread, and I was desperately staring at it, struggling not to skid. I automatically braked whenever the red lights of a truck entered my field of vision, and would narrowly miss crashing into the bike in front of me. I was driving in crisis management mode. And a voice inside me kept whispering, “But that’s how you’ve been living the past forty years, pal.” A sign caught by my headlights at the entrance to a bridge sent an electric shock through me: Berezina. We crossed the river without the slightest incident.

We found a small, Soviet-looking hotel outside which we lined up our vehicles. I collared Vitaly. “The new helmet you gave me in Smolensk this morning is dreadful! I drove the last few hours not seeing a thing.”

“I think I understand,” Vitaly said.

The helmet was new and I’d forgotten to pull off the smoky plastic film protecting the visor. I’d driven down sixty miles of Belarus night with a screen in front of my eyes.

Every evening, it would take twenty minutes to remove our layers of clothing. Once we’d turned our room into a Tangiers souk, we were directed to a tavern called The Emperor’s Bivouac. The door handle was shaped like a bicorn. An Olga with purple fingernails served beer to truck drivers, in a chalet decor. On the walls, there were battle maps of Berezina, a portrait of Kutuzov, a print of Napoleon: they cultivated memory of the event here. We downed gallons of cabbage soup and had to walk down the streets of Barysaw for a long time to get back home. The little town was a charming refrigerator, and Belarus quite a livable place. Decent people lived there slowly, diligently, in a modest, socialist wellbeing, while declining Europe was convinced they suffered martyrdom under the yoke of a satrap infused by the Kremlin. We collapsed into our beds instead of throwing ourselves into the encampment lights, like hundreds of Old Guard soldiers, who preferred death in the embers to frostbite…

DAY FIVE.

FROM BARYSAW TO VILNIUS

At 9 A.M. we were at the Barysaw Museum. Like in all the former Soviet Empire establishments, a dozen fat ladies in woolies were guarding empty rooms. The Napoleonic epic had at least created jobs. The museum was crammed with flags, uniforms, weapons, and wall maps streaked with red arrows. Every year, while ploughing, peasants would dig up cannon shafts, buttons, and rusty helmets. The museum had ended up declining the discoveries.

Goisque, who was a born archeologist, couldn’t pull himself away from the display of cannon balls. “Tesson, do you remember F.’s story?”

During our dinner in Moscow, our friend from Rostov-on-the-Don had told us about his adventure. He’d gotten used to going around the battlefields of the former USSR with a metal detector. One day, in the Berezina mudflats, his device started ringing. He parted the gorses, dug in the silt, and uncovered a ball. He had it identified and received confirmation of something he already knew: it was a piece of Napoleonic artillery. He drove back to the Saint Petersburg airport with his seven-pound treasure and showed up at boarding, with his ball in his hand baggage. No doubt his error was due to his naivety. No sooner had he gone through the security barrier than the arches began to ring, the authorities panicked, bags were searched, and the ball was discovered. Not bothering to explain how a plane could be destroyed with a 1812 cannon ball, the cops forbade him from boarding. Attached to his discovery, F. asked for ten minutes’ grace, left the airport terminal, saw a tree in the parking lot, glanced right and left, and dug a hole in the summer soil, and buried his treasure. Then, after writing down the exact location, he jumped on his plane, hoping to recover his possession some day. Several months later, our friend von Polier was taking some Russian businessmen very important to the survival of his business to Saint Petersburg airport. He had in his suit jacket pocket F.’s instructions and a map scribbled on a page from a school exercise book: “Two steps to the right after the parking meter, third birch from the barrier.” Von Polier asked the financiers to excuse him, “Just give me five minutes, gentlemen.” He ran out into the parking lot, found the cannon ball tree, and started digging. It was winter and the soil was frozen. And here’s this guy in a suit, crouching in a parking lot, busy digging the shoulder with his Montblanc pen. The cannonball brought back to Moscow by rail had place of honor on his piano, between a Golden Ring icon and a portrait of Lenin.

Читать дальше