What had happened for a nation to become an aggregate of individuals convinced they had nothing in common with others? Shopping, perhaps? Shopkeepers had managed to pull it off. For many of us, buying things had become a principal activity, a horizon, a destination. We were cultivating our gardens. That was probably preferable to fertilizing battlefields.

In Afghanistan, I’d had a conversation with two young French captains. We spoke for a long time, sitting on a rock, surrounded by the scent of artemisia. We asked ourselves what we would be ready to die for. Our country? I suggested. They exclaimed that they’d quite like to. But it should first be glorified by those who rule it. The young captains added with sadness that this was far from the case. The cause had collapsed. The very word was pedestrian. Nobody wants to die for a shameful idea. Who would throw himself into a game when you’re told it just isn’t worth it? It’s precisely there that Napoleon’s genius had been deployed. The Emperor had succeeded in an enterprise of exceptional propaganda. He had imposed his dream with the word. His vision had been made incarnate. France, the Empire, and he himself had become an object of desire, of a fantasy. He had managed to dazzle men, enthuse them, then involve them all in his project: from the lowliest conscript to the highest aristocrat.

He had told men something and the men had wanted to listen to a fairy story, and believe it could come true. Men are ready for anything, just as long as someone exalts them and the speaker is skillful.

The diminutive Corsican had used every publicity technique. He had staged his coronation, embraced a heritage without doing its inventory, and pictured a new aesthetic. He had distributed new titles, rewritten pedigrees, invented rewards. In his puppeteer hands a new court had been established. The system was based on merit: everybody could bring home the bacon and aspire to high office. You used to be a pork butcher’s boy? You could end up a marshal! It was no longer necessary to be of noble birth, as long as you were driven! He had produced slogans. His responses were imprinted in the collective unconscious. His letters and bulletins had acted as press releases for immediate business and archives for posterity. In battle, he had shaken up old rules. He had raised opportunism into an art of war. His military feats were theatrical. He had baffled war scholars, trusting in his lucky star, manhandling theories. Basking in victories, he had formed a geography of glory. Austerlitz, Wagram, Jena warmed the cockles of the heart, and inflamed minds. In the architecture of legend, he had neglected nothing: with the help of his Napoleonic Code, he had even endowed the Empire with its little red book!

The golden dome was glowing. Goisque had been busy. He had called the military governor of Paris and obtained permission for us drive our bikes into the main courtyard. We cut through a line of tourists. The Japanese were staring, eyes wide. The gendarmes moved back against the railings. Vitaly was proud. He wasn’t used to the constabulary holding the door open for him.

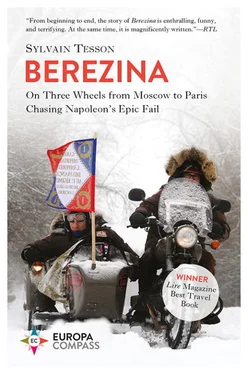

Our small column of Uralist-radical-Napoleonists, as Vassily called it, ventured onto the cobbles. We drove in a row, made half a turn to the left, parked our bikes, and cut our engines at the bottom of the courtyard, at the foot of Napoleon’s statue. We were a few yards away from his tomb. We had stretched an earthly thread from Moscow to this courtyard.

There were a few friends there. They’d come to hug us. They were surprised by the fact that we said nothing. We were just happy standing there, beneath the bronze statue.

I felt as though I was waking up after a two-and-a-half-thousand-mile-long dream.

Who was Napoleon? A wide-awake dreamer who believed life wasn’t enough? What was History? A faded dream of no use to our small-minded present?

The sky darkened, and a few drops fell.

I suddenly felt like going home, taking a shower, and washing off all those horrors.

Sylvain Tesson has traveled the world by bicycle, train, horse, motorcycle, and on foot. His best-selling accounts of his travels have won numerous prizes, including the Dolman Best Travel Book Award for The Consolations of the Forest: Alone in a Cabin on the Siberian Taiga (2013). He is also the president of an NGO, La Guilde Européenne du Raid.

Europa Editions

214 West 29th St.

New York NY 10001

info@europaeditions.com

www.europaeditions.com

Copyright © 2015 by Editions Guérin

Published by arrangement with Agence litteraire Astier-Pécher

All Rights Reserved

First publication 2019 by Europa Editions

Translation by Katherine Gregor

Original Title: Berezina

Translation copyright © 2019 by Europa Editions

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Cover Art by Emanuele Ragnisco

www.mekkanografici.com

Cover photo © www.thomasgoisque-photo.com

ISBN 9781609455552

Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales de Paris: a prestigious European business school based in the suburbs of Paris.

In Russia, you count the amount of alcohol you drink in grams. A small glass: 50 grams. A large glass: 100 grams. A wreck of a morning: 500 grams.

Published by Fayard, Paris

Ménéval (Claude François de): Dix ans avec Napoleon, Les Mémoires du secrétaire particulier de l’Empereur , Paris, Le Cherche-Midi, 2014.

Op. Cit.

Bourbon-Gravierre, organizer of the civilian hospice.

Pirsig (Robert M.), Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values (William and Morrow, 1974).

Title of Lionel Jospin’s brilliant (but debatable) book (Paris, Le Seuil, 2014), who shares with the Emperor the fact that he failed at a campaign.

Berkeley (George), A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge , 1710.