“So what’s the plan for today, guys?” I said.

“To visit the ramparts,” Vitaly said.

“Or what’s left of them,” Vitaly said, “since Napoleon destroyed quite a lot of them.”

“Then to Belarus,” Vitaly added.

We were excited by the prospect of entering Belarus territory. It was the only one of the fifteen former USSR republics—together with Turkmenistan—that I didn’t know. Two years earlier, Goisque and I had been at the Belarus Ambassador’s in France. On Boulevard Suchet. The man was an admirer of the Emperor. He kept a very “Empire” mustache and wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Cossack battalion. After telling us that Belarus was world famous for its production of bolts and space stations, he had entered into a strategic review of the Battle of Berezina, after which, two hours later, he’d exclaimed, “For you, Belarus will always have a green light and a red carpet !” Nevertheless, a few days later, our visa application had been denied because of some mysterious administrative misunderstanding. This year, we had obtained the precious blank signed papers and were planning on experiencing, in full, the green light and red carpet doctrine.

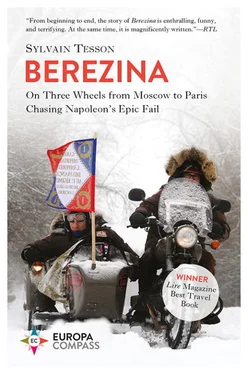

Vassily and Vitaly were very proud of their installation: they had decorated their engines with Russian imperial flags. The eagle with two heads flapped over their sidecars.

“People need to know who’s who,” Vitaly said.

Oh, how we loved these Russians. Back home, public opinion held them in contempt. The press, at most, took them for straight-haired brutes incapable of appreciating the amiable customs of Caucasus peoples, or the subtleties of social democracy and, at worse, a bunch of blue-eyed half-Asians who fully deserved the brutality and satraps under whose yoke they would get drunk on Armenian brandy while their women dreamed of strutting down the streets of Nice.

They were emerging from seventy years under the Soviet yoke. They had suffered ten years of Yeltsinian anarchy. Now, they were taking their revenge on the red century and returning to the world chessboard in large strides. They said things we considered dreadful: they were proud of their history, felt a surge of patriotic ideas, were overwhelmingly supportive of their president, wished to resist the hegemony of NATO, and opposed the idea of a Eurasianism that was close to Euro-Atlantism. Moreover, they didn’t think that the USA was yearning to take over the procedures of the former USSR. Heck! They’d become intolerable.

I’d been frequenting Russians since the failed coup by Gennady Yanayev in August 1991. They never seemed to be wracked with worry, calculation, rancor, or doubt: virtues of modernity. They looked like close cousins inhabiting a geographical belly bordering on the terribly windswept Tartary to the east and our crisis-ridden peninsula to the west. I felt tenderness for these plain and mountain Slavs whose handshakes crushed all desire to say hello to them again. I liked their fatalism, the way they announced tea with a whistle on a sunny afternoon, their taste for the tragic, their sense of the holy, their inability to get organized, their skill for throwing all their strength out of the window on the spot, their exhausting impulsiveness, their contempt for the future and anything resembling personal programs. Russians were the champions of the five-year plans because they were incapable of foreseeing what they themselves would be doing in the next five minutes. Even if they had known, “they would never reach their goals because they always went beyond them,” as Madame de Staël said. And then the first impression of roughness. A Russian never made an effort to charm you. “We’re not doormen at the Sheraton here,” they seemed to think while slamming the door in your face. In principle, they sulked, but I’ve known them to offer me their help as though I were their son and I preferred this kind of unpredictability to that of creatures who would clear off at the slightest sign of rain after patting your back with excessive familiarity.

Was it because History had let rip upon them with the rage of a swell against a tropical reef that they had developed a tragic view of life, a taste for permanently expressing sorrow, and a constant ability to proclaim the inconvenience of having been born ?

We Latins, fed on stoicism, watered by Montaigne, inspired by Proust, we tried to enjoy what happened to us, to grab happiness anywhere it happened to shimmer, see it when it appeared, and give it a name whenever there was an opportunity. In other words, we tried to live as soon as the wind rose. Russians, on the other hand, were convinced that you had to have suffered beforehand in order to appreciate things. Happiness was no more than an interlude in the tragic game of existence. Once, in an elevator rising from a coal mine, a Donbas miner summed up the Slav “difficulty of being” perfectly: “How do you know the sun if you haven’t been down a mine?”

Milan Kundera often deplored the lack of rationality in the Russian way of thinking. He was repelled by this tendency on the part of Dostoyevsky’s compatriots always to sentimentalize everything, to tarnish a life with pathos when they themselves were guilty of doing it. What if this was the key to the Russian mystery? An ability to leave everything behind in ruins to then water them with floods of tears.

Certainly, this journey was a way of honoring the manes of Sergeant Bourgogne and Prince Eugène, but also an opportunity to throw ourselves from potholes into bistros with two of our brothers from the East and seal our love for Russia, for crumbling roads, and for freezing mornings washing away drunken nights.

We drove to the Smolensk fortifications. I tried to picture this sleepy city consumed by fire and pillage. It was hard to distract myself from the babushkas coming back from the market or the female students in leather boots and dressed in fox furs, who, in Russia, always confuse sidewalks with Fashion Week catwalks.

Arriving here must have been such a disappointment for the soldiers of the Grande Armée . The wretches had dreamed of it so long! They thought this city was their promised land.

Hunger had started torturing them since the first weeks of the retreat. The horses, fed on straw torn off the thatched roofs of isbas , were growing weaker, buckling beneath the weight, and falling. Without waiting for them to be dead, the soldiers would throw themselves on them and tear them to pieces. After all, you robbed dying companions who had stumbled from exhaustion. You got rid of the wounded perched on saddles and allowed the animals to trot. Why then not skin the horses alive?

I was telling Gras what I had read the night before in Bourgogne’s story. Goisque was not listening, and was trying to fit the hotel building and the view over the Dnieper into his Japanese box. With the Cossacks on their heels, and no time even to cook the meat, the soldiers would plunge their heads into cauldrons of boiled blood. There were fights over a handful of potatoes. Beards and coats were stained in red. The cold froze the carcasses of the animals. You then had to scrape the hardened flesh with a sword. “Those who had no knives, no sabers, and no axes, and whose hands were frozen could not eat. […] I saw soldiers on their knees next to carcasses, biting into the flesh like hungry wolves,” Captain François recalls. Bourgogne himself survived for a few days sucking “blood icicles.” According to him, the military staff officially approved the idea that only horse meat could save the army: “They made us walk behind the cavalry as much as possible […] so that we may eat the horses they left behind.” Hence, the prediction of Kutuzov the Toad on the field of Borodino came true: “I will do all I can so the French will end up eating horse.”

Читать дальше