HERE’S TO ISMAY

At summer’s eve when Heaven’s ethereal bow

Spans with bright arch the glittering hills below,

Why to Ismay turns the prophetic eye.

Where grand possibilities so plent lie

Slumbering, but aphynx like, raises her infant head.

Telling how homeseekers daily tread

Her unfinished streets now rank with life

Where all is genial — no sign of strife!

Long may she thrive while countless homes do stand

On such abundant and fertile land.

While natives listen at eve’s alluring strains,

Blest little Ismay, youngest city of the plains!

A schoolteacher from Red Wing, Minnesota, out of long habit correcting the poem’s faulty spelling and grammar, picked up the echo of Oliver Goldsmith and his Deserted Village .

Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plain,

Where health and plenty cheered the labouring swain …

But Goldsmith was writing an elegy on a rural community destroyed by the big landowners. In Ismay, history was being miraculously rewritten. The cattle ranchers, who had lorded it over the plains, like the wealthy foxhunters with their parks and fake castles in Goldsmith’s poem, were being fenced out by the laboring swains. The ideal village was being reborn, the land restored to the virtuous cultivators of the earth. Blest little Ismay!

THE NEW ARRIVALS FOUND THEMSELVES IN COUNTRY that defeated the best efforts of the eye to get it in sharp focus. It went on interminably in every direction. In late summer (the season recommended to homesteaders as the best time of year to come to Montana), the yellow land looked like bad skin — a welter of blisters, pimples, bumps and boils. With no trees to frame it, no commanding hills to lend it depth and perspective, it gave people vertigo. You couldn’t get your bearings — or, rather, you had no sooner selected them than they went absent without leave. Was it this pimple? or that one? — or that one over there? It was scary country in which to take a stroll. You felt lost in it before you started.

It was not quite raw land , but nor was it a land scape . The northern plains had long ago been grooved by dainty-footed buffalo, then lightly patterned by winding Indian trails. Ranchers, driving cattle from Texas to Montana, left ribbons of trodden ground as broad as superhighways. The army, under generals like Custer, Miles and Terry, built compass-course military roads that marched up hill and down dale, disdainful of contours. The railroad companies ran tracks along the creek and river bottoms. Yet all these routes added up to no more than a few hairline scratches on the prairie.

You would need to know what to look for in order to notice the really important landscaping work — the wooden stakes, protruding twelve inches from the ground, and mostly hidden by the sagebrush. Since the 1870s, survey teams from the federal Land Office had been mapping Montana and turning it into a grid of six-mile-square “townships,” each subdivided into thirty-six sections, with every section pegged out into quarters.

The Rectangular Survey of the West was begun by Thomas Jefferson, who headed a 1784 Congressional committee which drafted the Land Ordinance of 1785. The project reflected both the rationalist, French Enlightenment temper of Jefferson’s mind and his personal interest in the craft of surveying. His father, Colonel Peter Jefferson, had led a survey of northern Virginia, and Jefferson grew up familiar with the instruments and the immense, finical labor of map making from scratch.

The Land Ordinance was a dizzyingly ambitious document. Beginning at an arbitrary point on the Ohio River, where it left Pennsylvania on a westward course, a vast, ghostly graticule of numbered squares was flung over the expanse of undiscovered, unsettled North America. On the slopes of mountains yet unseen, in valleys that were still the domain of unknown “savages,” grid-ded townships awaited the arrival of explorers like Lewis and Clark and surveyors (like Clark himself, who became Surveyor-General of Missouri in 1824, and his son, Meriwether Lewis Clark, who was appointed to the same post in 1849). In Jefferson’s scheme of things, the townships were out there, in the unknown world, as Platonic entities. To bring them into physical existence, they must be located and staked. Even as you hacked your way through the brush, you’d know the number of the township you were in and the number of the square-mile section on which you stood. According to the Ordinance, one section (No. 16, near the middle of each township) was to be reserved for educational use and four more were set aside for the U.S. government. So the unmapped townships were already equipped with ghostly schools and colleges, ghostly post offices, courthouses, barracks, licensing departments and all the rest of the machinery of an ordered civilization.

It took nearly 140 years to square up the West like a sheet of graph paper, and at the beginning of the twentieth century surveyors were still at work on the Montana prairie, laying down section lines with Burt’s Improved Solar Compass. Distance was measured off in chains, using a standard chain of a hundred links, sixty-six feet long, or one-eightieth of a mile. As the chain came taut, a chainman stuck in the ground a steel tally pin decorated with a red rag. At five chains, the forward chainman called “Tally!” and the rest of the chainmen came back in chorus, “Tally!” before the pins were removed and the gang moved on to the next stretch. At forty chains, a wooden post, thirty inches toll, with Arabic numerals neatly chiseled on its face, was set in a hole eighteen inches deep (the instructions in the survey manual resemble those of a religious ritual) to mark the quarter section.

Every chainman was sworn into office with the Chainman’s Oath:

I, ________, do solemnly swear that I will well and faithfully execute the duties of chainman; that I will level the chain upon even and uneven ground, and plumb the tally pins, either by sticking or dropping the same; that I will report the true distances to all notable objects, and the true length of all lines that I assist in measuring, to the best of my skill and ability, and in accordance with instructions given me.

Moundmen, axemen and flagmen took similar oaths — though none of this ceremonial gravity did much to hide the fact that a job on the Land Survey brought with it all sorts of interesting perks and opportunities. Of the fourteen surveyors-general of Montana between 1867 and 1925, two were removed from office, one was suspended and four were forced to resign. At the very least, a spell on a survey team could lead to a profitable career in real estate, and most of the locators, who showed up in their buggies at railroad stations whenever an emigrant train was expected, had done time on the Land Survey. For an ex-chainman, the locating business was money for jam at $25.00 for a light morning’s work.

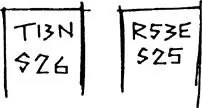

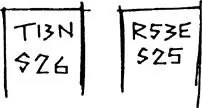

The locator knew exactly where he was. Leaving his horse in its traces to graze on the springy buffalo grass, he marched confidently across the prairie in high-heeled boots, and exposed a weathered stake. Coded messages were carved on it, front and back:

Four notches had been cut on one side of the stake, two on the other. Fearing to seem a fool, the client was shy of asking his locator what these symbols meant. Ten minutes later, after a jolting ride over the rough ground, the locator was at it again, using his boot toe to conjure from the undergrowth another stake; more letters, numbers, notches.

The locator was the Columbus of grass and sage. To the client, his navigational skills were uncanny: far out on the disorienting prairie, he was like a man pottering among the geraniums in his backyard. The locator’s easy familiarity with the land only made the client feel more confused. The stakes were lost to sight within a few yards. “Your place”—as the locator kept on calling it — was a brain-teasing abstraction. The moment you grasped it, it dissolved on you. A sandy hillock marked the southwestern corner of the property — but then you blinked, and the hillock was gone, and the place had slithered off elsewhere.

Читать дальше