When Jennie came in, the dogs hid under the sofa. They were afraid to death of her. Jennie sat at the kitchen table and carefully arranged all her tableware. And then she would sit there for an hour or more, waiting to be fed, fretting and hooting and chattering away. When she got older she got more impatient. She screamed and hooted as if we were starving her to death. Jennie just loved her food.

At first we fed her baby food. But it wasn’t long before she insisted on eating what we ate. She wanted to do everything we did. The food on her plate was never good enough; she had to eat ours. Most every morning, she ate a slice of buttered toast, a banana, and a bowl of oatmeal and honey. Once in a while she would eat a piece of bacon, but she didn’t like meat that much. Chicken and pork she would eat, but nothing else.

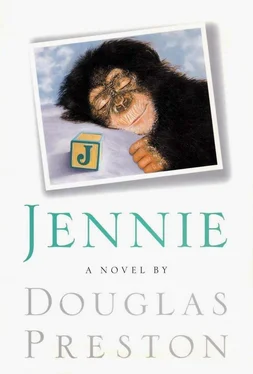

She looked so funny when she ate! You should have seen her, with her little black eyes peeping above the tabletop. Oh my goodness. And her wispy hair stuck up from the dome of her head in the funniest way, and she made these little crunching noises as she ate her toast. And those jug ears! They stuck out and looked like big pink Christmas lights when the sun was behind them. [Laughs.]

She was always suspicious about her food. Once in a while, you see, she would bite into something she hated. She sniffed at her food constantly. I suppose she was never sure when that piece of toast might turn into, say, a hamburger with ketchup. She loathed hamburger with ketchup! And pickles. If there was pickle in there somewhere, watch out! When she got something she didn’t like, she picked it up and threw it as hard as she could into the dining room. Tomatoes, baked beans, lobster, steak — all got thrown into the dining room at one time or another. I think she got that idea from watching the Three Stooges on television. They were always throwing food on that horrid program. Jennie could be so trying at times. There was a streak of ketchup on the kitchen ceiling from one of Jennie’s hamburgers. It stayed there for years, long after Jennie was gone. It used to make me feel so sad, but I could never bring myself to get a ladder and scrub it off. It was like a memory; you hate to see them go. Memories, I mean.

Jennie looked so solemn when she was eating that you couldn’t help laughing. When she chewed, the little hairs on her chin moved up and down and her eyebrows contracted as if she were thinking great thoughts. Well perhaps she was! After us, food was the most important thing in her life.

When she finished eating, there was no separating Jennie from her plate, cup, and spoon for washing. Heavens no. She guarded those with her life. She thought she would starve to death if those disappeared. She had a fit when I tried to wash them. They got so dirty, so absolutely filthy, that I was positive Jennie was going to get salmonella poisoning and spread it to the whole family. Finally Hugo waited under the tree one morning and stole them when Jennie dropped them. You should have heard her screaming. After that she let us have them, but she always kept her beady eyes fixed on them while I rinsed and loaded them in the dishwasher. Then she would wait right next to the dishwasher until they were done. The minute it was opened she would be reaching in there, rummaging about and rattling things around to get her precious tableware.

After three years she began rinsing the dishes herself. She wasn’t exactly the most thorough dishwasher, but she had her style. First she licked the plates clean, and then she washed them. I can’t begin to tell you how many dishes she broke. But when we had guests, the highlight of the evening was when Jennie cleared the table and rinsed the dishes. People could not get over the fact that an animal could do such a thing. They would always say, Will you look at that! We have to get one of our own! And then Jennie would drop a stack of dishes. Or take a bite out of a bar of soap. And that would be the end of that kind of talk! Hugo took a marvelous picture of her washing the dishes. Now let’s see, where are those pictures? Do you want to see any?

Those first few years with Jennie were blissful. It was a happy period in our lives. Jennie made it a great adventure. Not that it was easy; toilet training Jennie was the hardest thing I think I’ve ever done. Oh my goodness! That ape was not going to be toilet trained, if it was the last thing she did. She tried, but it wasn’t in her nature. When you live in the trees all day, I don’t suppose it really matters where you go. I developed a system where I’d give her candy when she did it “right.” She would do anything for a piece of candy. She tried so hard. It was so dear. She’d be playing in the kitchen, and I’d see this expression on her face. And she’d run for the bathroom! And on the way there she’d stop and stick her hand in the candy jar. That was fatal. Sometimes her reward was a little premature, and — oh dear — her diaper would be all soggy. And then do you know what she did? She’d put the candy back. All by herself. Jennie was so human, so utterly human. You had to see it to believe it.

[FROM Recollecting a Life by Hugo Archibald.]

Jennie settled into suburban American life as if she had been born to it. She quickly developed a taste for television. We owned one of the latest models, a Vision-Aire De Luxe, molded in space-age brown plastic, with a bulbous screen and silver-painted dials. It cost $99.95, a large sum in those days. Jennie became an addict, and as long as the television was on she was content for hours at a time. In retrospect, I often wonder what effect the violence and aggression of television might have had on Jennie. In the mid-sixties, however, television was more benign than it is today, and it was even thought to be educational. Children were considered deprived if there was no television in the house.

Jennie’s consumption of television was on the vocal side. While she watched, a stream of grunts, hoots, and squeaks issued from the den, punctuated by stamping or pounding during particularly exciting scenes, such as car chases and gunfights. She also favored programming that involved canned laughter. Human laughter fascinated her.

We first had an inkling of Jennie’s fondness for television one Saturday shortly after my return from Africa. I woke up to the faint sounds of the television set floating up from the den. Watching the television was an early Saturday morning ritual with Sandy. It was an oddly comforting sound, one I had not heard in six months.

I found the two of them sitting cross-legged, Indian-style, on the carpet, watching the Three Stooges. Even after all these years I remember that particular program. The action was taking place in an elegant drawing room filled with people in formal dress, and the Three Stooges, themselves dressed in evening clothes, were throwing pies and food and rapping each other on the head and poking each other in the eyes, to the usual sound effects of squawking horns and pizzicato violins. I asked Sandy what the point of all this was, and I remember him explaining that a professor, as an experiment, had tried to make gentlemen out of the Three Stooges. This was the unhappy result. It was a takeoff on Pygmalion and it was particularly apt that Jennie found it amusing.

Jennie was transfixed, staring at the screen. Her little eyes glittered. I wondered what her simian brain was making of the program.

“Dad! Jennie likes to watch TV!” Sandy cried, as if reporting a revelation. “Watch!”

He turned off the television set and sat back. The screen contracted to a point. Without missing a beat, Jennie scooted over and turned it back on.

“He he heee!” she said as the picture slowly focused. She gripped the sides of the television and hopped up and down, her face inches from the screen.

Читать дальше