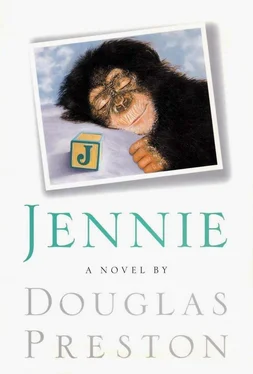

I saw no alternative but to sacrifice my dignity and crawl under the chaise myself to retrieve the chimp and the hat. I grabbed Jennie by the foot and dragged her out. Her piercing screams filled the room, sounding for all the world as if she were being stretched on the rack.

“The poor thing,” said the Reverend. “She’s frightened.”

“With good reason,” I said, seizing the hat from her head and dragging her toward the bathroom. I locked her in. Her pounding and muffled screams gave the house the air of a nineteenth-century insane asylum.

When I returned, I found Lea still apologizing while the Reverend turned his hat over in his hands. Jennie’s five minutes with the hat had completely destroyed it.

“The poor thing,” said the Reverend, almost to himself, and then it all came out in a stammered jumble. “My wife is afraid of animals. She isn’t too keen on the idea of having a monkey in the neighborhood.”

There was a silence. What he had been sent over to say had just been said.

“I, myself, have always liked animals,” he added wistfully.

“I just can’t understand Jennie’s behavior—” Lea began again, not very convincingly.

“I’m sure,” I said, “that as Jennie gets a little older she’ll settle down.”

As if on cue the screaming redoubled and the Reverend winced. “I hate for her to be in there on my account.”

We talked some more, rapid exchanges of small talk spoken during lulls in the storm. Then, from upstairs, the sleeping baby woke and also began to howl. Lea went up to get her while I released Jennie from her imprisonment.

As soon as the door opened her cries ceased, and she looked up at me with the most pathetically sad and frightened little face. She waddled over and opened her arms to be hugged, looking contrite. I carried her back into the living room.

Palliser sat on the sofa, looking rather at a loss, his hands folded on the table. Jennie climbed down and laid her hand on his and made a low, mournful hoot. Lea came down with the baby.

“Oh,” said the Reverend to Jennie. “You’re sorry. You want to say you’re sorry.”

Jennie hopped up on the sofa and opened her arms for a hug. Palliser picked her up and hugged her, her furry head briefly nestling against his bald pate.

“What a darling,” the Reverend said, a little breathlessly. “I do think she likes me. Yes, indeed, I do.”

Jennie sat in his lap, playing with one of his buttons.

“Aren’t you a nice girl,” he said again, patting her back. “Here, a welcome-to-America present for you,” and he gave her back the hat. Jennie snatched it and clapped it on her head. Then she gave a big hoot and jumped to the floor and began strutting around.

“You don’t have to do that,” I said to Palliser.

“Oh, but I want to. She’s very cute in a hat. Every monkey needs a hat, right, Jennie?” He turned to us, beaming, as if he were the father himself.

Jennie spun around and came strutting back, clacking her teeth with happiness.

The Reverend finally rose to leave. “We won’t say anything about this to Mrs. Palliser,” he said, stammering slightly and turning red with embarrassment. “The hat was a gift from her. But I never really liked it; I’m not a hat person, you know. She feels I ought to be covering up my baldness. One doesn’t, so she tells me, expose one’s baldness these days. I’ll say I lost it.”

He scurried out the door.

“Oh no,” said Lea, looking out the window, “there she is, on the stoop, waiting to hear the news.”

I saw that the very thick Mrs. Palliser was indeed standing in the door, with a sour expression on her face.

“What an oddly pleasant fellow,” said Lea. “Jennie seems to have won him over. He’s not at all what I expected.”

“I don’t think there will be any winning over the wife,” I said, watching her follow him into the house with a firm shutting of the door.

[FROM taped interviews with Dr. Harold Epstein, Curator Emeritus, Department of Anthropology, Boston Museum of Natural History, in his office at the museum in July 1991, November 1992, and January 1993.]

Do you know the expression “Words pay no debts?” There is, you see, nothing I can tell you that will change anything. Or pay any debts. We’re here because almost everything that was written about this thing was a pack of lies. You’re finally going to tell the truth.

The “Jennie period,” as I like to call it, took place between 1965 and 1974. I was head of the department. Hugo was about twenty years my junior and was the Curator of Physical Anthropology. Hugo assumed the chairmanship when I retired in 1974. Until this Jennie business, he was one of the most capable and creative scientists the museum had the privilege to employ.

The museum? It hasn’t changed its appearance in one hundred and forty years. It’s like Churchill said, it was ugly yesterday, it’s ugly today, and it’ll wake up just as ugly tomorrow morning. I always thought it looked like a grim Crusader castle. When it rains, those rooftop gargoyles spout water. At dusk, bats drop down from the eaves and swoop about. They scare the secretaries. The museum park used to be surrounded by a great wrought-iron fence with spikes. They took it down when someone jumped off the roof and landed on it. They had to cut out a piece of fence, you see. The spikes had gone clear through the fellow’s gut. It was one of those A.B.D.s finally giving up. A.B.D.? It means “All But Dissertation.” The museum is full of them, graduate students who are incapable of finishing their dissertations. They stay on for years, living off grants, examining specimens, gathering data, wandering about the halls.

That statue out front is Thierry de Louliz, venerable founder of the museum. It is always covered with pigeon lime: pigeons love to defecate on his head. It is a perfectly absurd statue, the old man holding that fossil fish like Napoleon with his sword. He was much feared and hated during his lifetime, but I think he looks like a dotty old uncle, cutting a ridiculous figure among the sycamores. I have not, thank goodness, accomplished enough in my life to be awarded a postmortem statue. Louliz’s great accomplishment was to dogmatically oppose Darwin’s theory of natural selection to the bitter end. I mean, to the bitter end of Louliz . His last words were, “Zis Darwin, I tell you, iss a great fool.” [Laughs.]

The building inside had a most peculiar smell. A combination of damp granite, cheap cleaning fluids, and old buckram. Plus a faint smell of mortification. Dead flesh. There were a lot of dead things in the museum. Some thirty million specimens. Two million in the osteological collection — that’s bones — and another three million alcoholics. Alcoholics, my friend, is what we term animals preserved in jars of fluid. Millions of insects and spiders. Snakes, tortoises, frogs and salamanders, rocks and minerals, meteorites, you name it. Ten thousand human skeletons and several hundred mummies. Not Egyptian mummies, but Indians, Aleuts, Tierra del Fuegans, those sorts of people. The collection represents a history of graverobbing, murder, and mayhem stretching back one hundred and forty years. I am being facetious, of course. Don’t print that. I’m eighty-five years old, and I have gotten into the habit of saying whatever I damn well please.

To get to the old Anthropology Department, one had to walk through the African Hall, past an archway framed by a brace of elephant tusks, world record size. The elephant was bagged by some bloodthirsty trustee of the museum in the 1920s. Hugo Archibald was a physical anthropologist, a collector of dead specimens. I am a cultural anthropologist — I study the living. His research was on the phylogeny of the primates. He spent years in Africa, Asia, and South America, collecting specimens.

Читать дальше