“I see.”

“Jen ikwa si go . Dat be his palaver.”

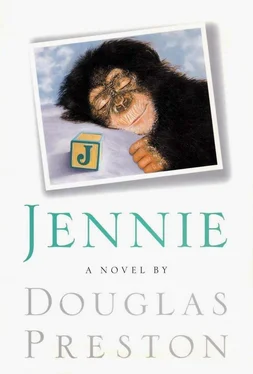

I thought about this. I had been having some difficulty thinking of a name for the animal. I have always had trouble with names, and it was my wife, Lea, who had to choose names for our two children, Sarah and Alexander. For six months I had struggled to name the animal, but they all sounded awkward and flat and in the end I’d been too embarrassed to voice any of them out loud. Jen-Ikwa-Si-Go. Little-Animal-Who-Bristles-Herself-up-to-Look-Big. It sounded like a fine name to me. I called her Jennie.

[FROM interviews with Mrs. Hugo Archibald, January 1991, October 1991, and September 1992 at her apartment in Kibbencook Lower Falls, Massachusetts.]

Is that really necessary? I don’t like tape recorders. They make me nervous. Well, if you insist. Yes, I talked to Dr. Epstein. What a clever, sly old man he is, the way he stares at you with those beady eyes. He’s always been a wrinkled old man, as long as I’ve known him. He was one of those people born old. I’m not sure I altogether trust his judgment of people. He’s too clever for his own good. I hope he’s right about you. He said you were going to set the story straight.

Where shall we begin? It’s such a terribly long story, I’m not sure I’m up to going through the whole thing. Oh dear. I’m just an old lady now. How long is this going to take?

We lived in Kibbencook proper, about a mile from here. Our house? It was a rambling, seedy old place. Hugo loved it. I found it nearly impossible to keep house. It wasn’t a nice suburban house by any means. It was too big and rambling. And not very chimpproof. When we bought it we weren’t exactly thinking about having a chimpanzee. The yard was full of dandelions. How the neighbors hated that! It was enclosed by the most awful hedge. A diseased-looking thing, all gapped and yellow. We tried everything, but every year a little more of it died. The lawn had big brown patches all over it. And the rhododendrons! They were so overgrown they grew up to the second story windows and when the wind blew we could hear the scraping noises from inside. It used to scare the children. Hugo told them it was a bear outside. In the side yard was a marvelous old crabapple tree, with sagging limbs propped up on sticks. Behind that was the Kibbencook golf course. Our yard was not the envy of our neighbors, to say the least. [Laughs.] Hugo was not exactly interested in lawn care. And I certainly was not going to start pushing around a lawn mower.

Kibbencook was a lovely town. Very quiet. Not like it is today. Those horrid town houses along Washington Street hadn’t gone up, and the bandstand was still in the square. Kibbencook had once been an Indian settlement along the Charles River. You can still see their shell heaps down by the river. Do you know Route 9, that dreadful strip with all the gas stations? That was once the Kibbencook Trace, the old Indian trail that went to Boston Harbor. The Indians had villages along the brook, where the golf course is today. Once in a while a golfer would lose a ball in the brook and find an arrowhead where the bank was eroding. Every golfer seemed to have an arrowhead. Sandy, our son, used to trade golf balls for those arrowheads. Golf is a ridiculous game. My father, who was of English descent, used to call it a Presbyterian game. Of course I married a Presbyterian, but thank goodness he didn’t golf.

I don’t suppose this has anything to do with Jennie. If I get off the subject you just interrupt me and set me back on track. Don’t you let me wander about.

Our house had once been the old farmhouse of the area, before the suburbs sprang up. In the woods behind the house you could still see the farm’s old stone walls. It was never good land. The glaciers dumped too many boulders on it. When the Midwest opened up, all the farmers left and the woods grew back. Now, of course, they’re cutting them all down again to build more houses.

There is a great deal of history in this town, only most of the people here are ignorant. The only thing they know is real estate values. They could tell you to the dollar what any one of these houses is worth. Half of the women here are real estate brokers. Real estate is what you do if you have no talent or education. Is that tape recorder still going? Perhaps you should edit my comments; I’m just a crabby old lady, you know. I can scarcely believe what has happened to the price of real estate in this town. I don’t know where people are getting the money.

They tore down the town hall, a lovely example of Romanesque Revival architecture, and put up that concrete cube. Appalling. The things they’ve done to this town. Why, only ten years ago they tried to blast out that big rock down by the brook. They thought it was an eyesore. So I went down there and I sat on that beautiful rock. For three days. And I said, “If you touch me, I’ll call my lawyer!” I outlasted them. It made them hopping mad, but then the papers took it up and—

Now you’ve let me get off the subject again.

The name of the town? Now that has a curious history. It originated with an Indian ruler named Kibenquot. He held court right here at this bend of the Charles River. But when the white men came he was corrupted by whiskey and money and sold the land out from under the tribe. They all died out. The only thing left were those arrowheads they’d find along the brook.

It was a lovely place back then. The woods and fields were endless, not like it is today. It was a wonderful place to raise children. Or a chimpanzee, for that matter. [Laughs.]

Our house was number sixteen Hawthorne Lane. It was angled to the street, not facing it like the other houses. It was a rickety old thing. The roof sagged, the porch was rotten, and it had been painted so many times that once in a while a piece of paint the size of a dinner plate would fall off. Long after the farm was gone, the farmer’s widow lived in it until they hauled her off to the nursing home. Hugo and I bought it in 1957, for $22,000. Now I expect it’s worth half a million. I wish them luck, whoever lives in it now. Probably some stockbroker. I wonder if they know a chimpanzee grew up there?

We were not popular in the neighborhood. We didn’t join the country club, we didn’t have barbecues in the backyard, and we had friends from Cambridge who looked Jewish. They say Massachusetts is a liberal state, but the only people we ever met in Kibbencook were Republicans. It was a very narrow-minded town.

When Jennie arrived, we became famous. Or perhaps I should say infamous! It was all great fun, in the beginning anyway.

Yes, indeed, I remember when Hugo returned from Africa with Jennie. He was supposed to come home on a Thursday and he arrived on Tuesday. I heard the cab in the driveway, gunning his engine, and there was Hugo, standing there with those two great ugly suitcases of his and a canvas sack slung around his neck. Sandy shot out the door with the two dogs on his heels. Such a commotion. I had the baby in my arms. She was squirming around like a coiled spring, trying to see what all the excitement was. She was only two months old when Hugo left, and this was six months later, mind you.

Hugo gave me a big kiss and he stepped back with a silly grin on his face. And he said he had a surprise for me.

He looked just like a mischievous boy when he reached into that bag. I thought he was going to pull out a snake. Instead out came this tiny thing, dangling by its arms. For the life of me I didn’t know what it was. The little thing blinked, looked around, hooted, and swung up into the crook of his arm. I was never so surprised in my life. It was Sandy who figured it out first.

He started screaming, “A monkey! Daddy brought us a monkey!”

Читать дальше