“Thank you, Kwele,” I said. Kwele grinned again, then scowled at the men.

The men shuffled their feet in the dust.

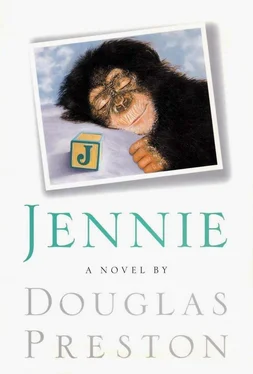

The animal was a female Pan troglodytes , a lowland chimpanzee, and she was very pregnant.

“You kill this beef with poison arrow?” I asked the two men.

One of the men stepped forward. “He go for stick, sah, shoot um with arrow.” He held up the crossbow for me to inspect. (“Stick” is the Pidgin word for tree.)

I knelt by the animal and looked at her face. The eyes, which were half open, suddenly widened. It gave me quite a fright; the bite of a chimpanzee can break one’s arm.

“Whah! Na alive, dis beef!” shouted Kwele accusingly, delighted to find one more thing wrong with the specimen. “Mebbe ’ee go hurt Masa! Den you go pay!”

“Poison be working,” said one of the men placidly. “Ee go die one time.” Then he added, firmly: “Masa gone pay twenty-five shillings.”

“Na whatee!” cried Kwele. “Masa no go pay twenty-five shillings. Mebbe ’ee no go die attall!”

“ ’Ee go die one time,” the man repeated stolidly. He knew the efficacy of his poison, and so did I.

The dying animal stared at me with round dark eyes, and a gurgle sound issued from her throat. Her mouth opened, exposing a row of worn, heavily caried incisors. The hairs around her muzzle were gray, and one ear was in tatters, torn and healed long ago. She was old, and I remember thinking, Better to die old after a full life. And, of course, they would have killed her for food anyway.

“Go get my pistol,” I said. Kwele ducked into the tent and came back with the holster carrying my Ruger .22 magnum. I checked the barrel to make sure it was loaded and leveled the gun at the animal’s heart. A shot to the head would have destroyed the thing I needed for my taxonomic studies: the skull.

Then a movement began to take place, a quick even movement of the animal’s body. I backed up, thinking she might be reviving. But then I realized something far different was going on. The animal was aborting her fetus.

“Roll her on her back,” I shouted.

There was a sudden sharp murmur from the crowd; this was turning out to be far more interesting than yet another bargaining session for a dead specimen. The female chimpanzee began to shudder, and a whitish head, slick with thin black hairs, appeared. In a second it was over. The fetus lay on its side in the dust, and the afterbirth was sliding out. The mother’s eyes were still open, looking.

Then I heard it: a tiny whistle; a thin simian cry.

“This thing’s alive!” I said. “Kwele, go get a basin of water. You, hunter man, get back.”

The crowd shoved forward and for a moment I thought the baby would be trampled.

“Back!” I cried.

I picked it up and, not knowing what else to do — and feeling more than a little foolish — I whacked it lightly on the back. The thing whistled and squeaked. I called for a machete and one was thrust into my hands; as I cut the umbilical cord a great “Ahhh!” rose from the crowd.

“Help me,” I said to Kwele, who had returned with a sloshing basin. “Help me wash it. And you all, get back! You no go push, you hear! Go back to work!”

The crowd backed up, jostling each other. No one went back to work.

We washed it in the basin and Kwele held it while I carefully towled it dry. The baby chimpanzee had a white face, and fine black hair covering its body. It was a female. The hair was very long and as it dried it fluffed out from the chimp’s body. When the animal was dry I wrapped her in the towel and cradled her in my arms. She had an impossibly tiny face, wrinkled and owlish, and her eyes were open. In a curious way her face looked both sorrowful and wise, as if she had seen a great deal of the world and its troubles. Which was amusing, since the only thing she had seen so far in the world was my unshaven face hovering over hers. It cried again, a very small sound, and the eyes widened and looked into my face. A wobbly arm, no bigger than a twig, reached up with five little fingers spread wide and groping, and it touched me on my chin. It was a sweet gesture, and in that brief moment, I was hopelessly entranced.

I have been asked many times why I took such a fancy to this little animal. My only answer is this: if you had been there, if you had seen this tiny little animal, with the pot belly and the surprised beady eyes peering at the world for the first time, and heard its helpless voice, you would have been won over just as I was. Perhaps this sounds overly sentimental coming from a scientist whose career had been collecting dead chimpanzees and examining their skeletons. I cannot, in the end, defend my sentimentality, except to say that scientists are human beings too. It was an utterly enchanting little animal.

When I recovered my senses I heard the sounds of an argument. Kwele was sweating and gesturing broadly at the two men, but the two men were not even looking at Kwele. They were looking at me. What they saw had, apparently, encouraged them to raise the price.

“Na whatee!” Kwele was shouting. “Masa done hear? Hunter man want de bigger dash! Fifty shillings! Hunter man no palaver with Masa no more. Get out! Go away!” He advanced at the men, flapping his arms like a big buzzard. They stood their ground, their faces without expression. The female chimpanzee lay on her back on the ground, momentarily forgotten, but still looking with strange terrible eyes at me and her baby.

The look in those dying eyes will never leave me. They stared upward like two cloudy gemstones, colorless, without light. The poison in the arrow that had struck her was, in chemical structure, like curare; it paralyzed first, killed second. It is not a merciful death: one dies fully conscious and aware of one’s surroundings. The Africans call it chupu . It is a high-molecular-weight globulin protein, and as such it could not penetrate the placental barrier, which is why the infant was spared its effects. Looking back across nearly twenty-five years, knowing now what I did not know then — it seems to me it was a prophetic look, a gaze not at the present but into the future. I have always wondered: what was she thinking, as she hovered between life and death, when she saw this strange, white, hairless primate gently cradling her baby?

If this sounds like strange talk from a scientist — so be it. If there is one thing I have learned from a lifetime study of science, it is that the world is not a place we human beings will ever comprehend. Understand, yes; comprehend, no. The reason for this — like the reason for almost everything in the way we think — is evolution: our brains did not evolve to help us comprehend the true meaning of things, only to understand their mechanical workings. Knowing the true meaning of reality does not contribute to one’s ability to survive, and thus this kind of understanding was not addressed by evolution.

I averted my eyes from that intense dying stare, and found myself looking at Kwele. “Fifty shillings!” he repeated. “Hunter man be robber man!”

“We don’t want the female,” I said, and then to make sure I was understood, repeated it again in Pidgin: “Masa no want dis beef. Kwele, shoot dis beef and tell hunter man to take it and get the hell out. Tell hunter man go for bush. Give him the fifty shillings.”

“Ndefa mu! Fifty shillings! Up de twenty-five! Masa!”

“For God’s sake, be quiet and give the man fifty shillings,” I said, and went back into my tent, pulling the flap shut, with the baby in my arms. I could hear more shouting, a chorus of voices raised in discussion. Then there was a sudden hush, the sharp crack of the Ruger, and another swell of argument. After a while the talk died away and the camp became quiet.

Читать дальше