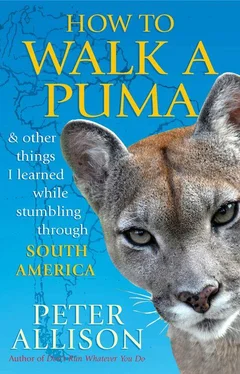

As the soldiers stood beside the car with their sampling tool, Mick said calmly, ‘Dare you to use it,’ and whipped back the blanket. Roy’s eyes were frozen open in the very same stare he used when about to attack, and both soldiers jumped back.

‘Puma!’ one of them exclaimed, quite unnecessarily.

In rapid-fire, urgent-sounding Spanish, Luis quickly explained our mission, and that we had to hurry as the puma could wake up at any moment and might become dangerous; he held up the syringe to emphasise his point.

The soldiers quickly waved us on. The look of mingled glee and excitement on their faces highlighted how young they were and how magnificent even a sleeping puma can be.

Finally arriving at the hospital after another half hour, we rushed Roy through the swinging doors, mindful as ever of his tail, then around a corner into a windowless corridor whose light fixtures had more blown bulbs than live ones.

We were met by a man wearing a beanie. He had a pair of glasses perched on his nose with lenses of such remarkable thickness that his neck must have felt the strain of the weight of them.

‘ Radioliga ,’ Luis said, and even with my limited Spanish I could guess at the man’s profession.

We carefully lifted Roy off the stretcher, and laid him on the radiologist’s table. His eyes were still wide open, and every now and then he would rumble through rubbery lips. The radiologist backed away, probably afraid, I thought, and wondered if he’d heard of Roy’s reputation for de-spleening Bolivians. But then I heard a switch being flicked, followed by an indistinct buzzing. Glancing over, I was appalled to see the radiologist behind a screen, presumably lead, accompanied by a nurse. Surely they had heard of Marie Curie? Surely they should have warned us before releasing radioactive waves? The radiologist spoke to the vets, who repositioned Roy, and again with no preamble he flicked the switch. I was sure I felt hair growing on parts of my body where it had never grown before.

‘Bloody hell,’ Mick said. ‘I think my nuts just shrank!’

It was only then that I noticed the radiologist was missing an arm from the elbow down. I nudged Bondy. ‘Do you think he’s met Roy before?’

We laughed, then the machine fired yet again and we left the room in a hurry, shooting spiteful glances at the one-armed man and covering our most delicate jewels as we went.

Once the plates were taken, the vets (who had stoically stayed in the room during the procedure) ushered us back in and we stretchered Roy out. News of his presence in the hospital had spread and a small crowd had gathered once again. Visitors, nurses, local children, and patients in vomit-green robes clustered in the hall. It was easy, if unfair, to be angry with Bolivians in general for what had been done to the animals that had ended up at the park, but these people showed a real awe at seeing Roy and I wondered if this was a small incidental opportunity to raise awareness of the need for puma preservation. It was impossible to know, but I was glad to be there, and waved as we all climbed into the back of the waiting taxi.

‘ Ciao! ’ a small child shouted cheerily, and soon the gathered crowd all started waving, calling ‘ ciao ’ to the big cat they’d just seen.

As the taxi began to pull away I waved and called, ‘ Ciao! ’

‘ Ciao! ’ echoed Bondy. ‘Meow!’ shouted Mick.

Roy showed signs of waking on the ride back and was given another sedative. Though he was drugged the drive may still have been traumatic for him, but it was even more stressful for those of us wedged into a confined space with a puma who might wake at any time.

With slightly jangled nerves we arrived at the drug checkpoint again. There were more soldiers than before, and we were waved away from the other cars towards a sinister-looking section out of sight of the road. A soldier with more stripes than the others approached the taxi, followed by his minions. ‘Bugger,’ I thought, ‘we’re in trouble.’ Paperwork could take hours in a place like this— hours and perhaps bribes that none of us had.

The officer pulled back the blanket that covered Roy, gave a ‘hmmph’ of triumph, then turned and spoke in Spanish to his assembled men. One of the soldiers whipped a small camera out of his pocket, and the officer quickly struck a pose beside Roy’s form, had his portrait taken, said ‘ Gracias ,’ and signalled us to drive on.

I learnt later that the region of Bolivia where Parque Machia is located is, after Ecuador and Peru, the third-largest coca-growing area in the world. The drug checkpoint we’d encountered on the way to and from the hospital was a permanent fixture, required if the country was to continue receiving US aid dollars. However, since it was known to everyone in the area and beyond, it was about as effective as fish-scented deodorant.

Unfortunately, the local coca growers, supported by the mayor, had started to build an illegal road around the checkpoint, bulldozing a swathe through the jungle, even toppling trees onto an enclosure where monkeys were being rehabilitated. If completed, the road had the potential to shut down Parque Machia altogether. By law, the mayor would then be in a position to dictate which animals were moved to other reserves and which stayed. As the tourists who came to the area often expressed dismay that they were not allowed near the pumas or ocelots, undoubtedly the mayor would want to keep some of these animals. Without the Inti Wara Yassi volunteers to walk them every day, they would need to be kept in cages. Ominously, only the rainy season was holding back the completion of the coca growers’ road.

•

The results of the X-ray revealed that Roy was suffering from a serious calcium deficiency, most likely congenital.

‘Man, his bones looked like a bird’s,’ said Rob, a Californian animal lover who donated several months of each year to Inti Wara Yassi, and who had known Roy for years. He’d become something of an expert on captive big cats. Rob and the vets devised a plan to supplement Roy’s daily diet of chicken and beef with calcium powder. This had to be smeared all over Roy’s food each day, a revolting job for me, Adrian, Mick and any future Roy Boys.

‘I’m not sure I want him getting any stronger,’ I said to Adrian as we trudged up the trail to Roy’s enclosure one morning. The path still left me panting, despite the fitness I was gaining daily.

‘Me neither, but you know something?’ said Adrian. ‘Now that I know Roy isn’t well I feel a bit differently towards him. I’m not so angry with him when he’s being a bastard.’

I wished I felt the same way. But contrary to my hope of forming a special connection with the puma, it had become apparent that I was a target for Roy’s aggression. He was known to jump some people more than others—and I had turned out to be one of those people. I held no dislike for Roy, but no affection either. I just wanted to make it through each day, getting jumped on as little as possible.

When I first arrived there I’d considered staying longer than four weeks at Parque Machia, maybe even settling in this patch of Bolivian jungle for a few months. But after dealing with Roy for a while I just wanted to get through the time I’d signed on for, to prove to myself that I couldn’t be beaten by a girly-faced, chicken-boned, racist cat.

Don’t Eat My Hero

Parque Machia was in a state of nervous anticipation, the entire place humming with activity. We were expecting a famous visitor, someone well known to anyone with more than a passing interest in wildlife: Dame Jane Goodall, whose research into chimpanzees has changed the way we think about apes, ourselves, and how wildlife research is conducted, was visiting the reserve for a night. Accompanying her would be the founder of Inti Wara Yassi, Juan Carlos, and some of the orphans and homeless children in his charge.

Читать дальше