Most of the teams that arrived at Skwentna during the night have already headed up the trail. There will be 30 or more of them at Finger Lake by midday, all waiting out the afternoon heat before challenging the infamous Happy River Steps and the 20 miles of bad road on up to the Rainy Pass checkpoint. I’d have liked to push on with them but our slow speed didn’t get us here soon enough. We took six hours to cover 35 miles from Yentna Station; most teams needed only four. I can’t keep up with the speed merchants; I’ll have to run my own timetable and let the chips fall where they may.

Now, however, I have to take care of the team. The first task is to get the dogs settled in, look them over, and get some food and water into them. I start at the front of the team and work back, giving each dog a biscuit, then I reverse and work forward unsnapping tuglines; this is a signal we’ll stay here for awhile — and it also prevents them from inadvertently bolting with the sled while they’re still in the “go” mode. Then I work back to the sled again, pulling off booties and giving each dog a hands-on thank you which doubles as a quick once-over for any obvious problems.

When the dogs are comfortable I take my plastic bucket over to a much-used hole in the river ice for water, which I drag back to the sled and pour into the alcohol cooker. Getting the cooker going is a critically important step; it must be done quickly after arriving to make sure the dogs get food (and the soaked-up water) while they are still in a mood to eat; tired dogs sometimes will simply curl up and go to sleep, ignoring even the most appetizing meal. Because of the intense calorie and hydration demands during the race, the dogs absolutely must eat and drink on a regular schedule; even one missed meal can spell trouble.

Once the water is heating I pull my food bags over and open them; as I half-expected, some of the meat looks like it has melted and refrozen, so I decide not to feed it. The last thing I need is sick dogs from eating spoiled meat; it’s happened before and has knocked entire teams out of the race. I included alternative meats less vulnerable to thawing, so I should be okay. From my “people bag” I extract the booties and necklines and snaps and batteries and gloves and other equipment I’ll need for the next couple of legs and put the rest in my return bag. I’m thankful we can salvage our used and excess gear by shipping it back — none of us wants to waste any more than we must.

After 15 minutes over the hot blue alcohol flames, the water is steaming and I pour it into the buckets, in which I’ve assembled a mixture of dry dog food, frozen meat, and anything else I think will tempt the dogs to eat. While the food soaks, I help the vet check the dogs and work on any problems we find. Usually these focus on feet, wrists, and sometimes shoulders; many small irritations and cuts and aches can be treated on the spot. Diarrhea is another constant threat, and the vets have an extensive arsenal of medications to combat it.

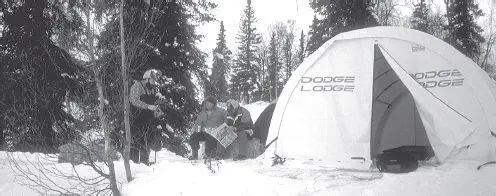

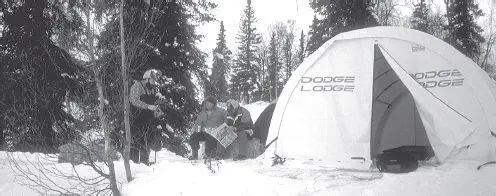

Most checkpoints are outfitted with sturdy quonset-type tents dubbed “Dodge Lodges.” They provide places for vets to work on sick or injured dogs or for tired mushers and volunteers to grab a quick nap. This one is at Finger Lake.

As I expected, my guys are in great shape except for some irritated feet from 100 miles of stomping through soft snow. As I kneel next to each dog I massage each afflicted paw with ointment; Martin Buser calls it “praying to the dogs” and I don’t think he’s too far wrong. The dogs are our central concern out here, and our efforts to keep them happy and in good health on the way to Nome may be closer to a prayer than most people realize.

When the dog food is ready, less than 45 minutes after we arrived, I feed it to the dogs, who devour it like I’ve starved them for a week. The sound of 16 dogs slurping water and food is probably the sweetest music any distance musher can hear: it means the dogs are healthy, eating, and well-hydrated.

Only after all this is done and the dogs have settled down in the warm morning sun can I worry about myself. This is all part of the routine I’ll repeat two dozen times between here and Nome. It will become so automatic I’ll be able to do it in my sleep in a few days, and I may well have to. The professional racers have this checkpoint routine down to a fine art. Minutes are precious in their end of the business, and the faster they get the dogs fed and bedded down, the more time they have for a nap and the sooner they can be on their way.

By now barely half a dozen teams remain here; last night more than 40 crowded every square foot of the river. It’s quiet now and at least my guys will get some quality rest. I climb the steep river bank to the checkpoint, located as always in Joe and Norma Delia’s spacious cabin overlooking the river. Breakfast is waiting inside, courtesy of the Skwentna Sweeties. As I shamelessly stuff myself with bacon, eggs, and sourdough pancakes I catch up on the race grapevine.

The most shocking news is that one of Rick Swenson’s dogs died in the overflow back at Moose Creek. This is especially confounding given Rick’s spotless history: he has never had a casualty in 20 years of running the race. No one knows whether the dog, Ariel, drowned or died of shock or something less obvious, but now the musher with the most impeccable record of dog care in the history of the race stands to be thrown out by virtue of the nefarious Rule 18.

I sympathize with Race Marshal Bobby Lee, who must be under incredible pressure right now as a member of the three-person committee deciding Rick’s fate. An Iditarod veteran himself, he was the only member of the Rules Committee to oppose the expired dog rule, and now he is in the impossible position of probably having to eject one of the top contenders from the race because of it. If he lets Rick go on, there will inevitably be cries of favoritism; after all, what if it had been me or another unknown musher? Any of us lesser lights would have been dumped without so much as a thank you. If he pulls Rick, he’ll become the lightning rod for criticism from all quarters, or worse, he will be accused of carrying out some kind of imagined vendetta against Swenson.

It’s a no-win situation, but I’ve known Bobby for some time and I’m certain he will make an honorable and fair decision based on the rule as it is written, even though he makes no secret of his dislike for it. In the meantime, the race judges have allowed Rick to continue to Rainy Pass, where they will let him know their ruling. I can’t imagine how he must feel. Many of us agree he has the best team in the race and we know how much time and effort he’s put into it. To risk losing everything on what is basically a roll of the dice, an act of God over which he had no control, is not fair — but that’s the way the rule reads. It’s unfortunate, but maybe it will take withdrawing someone as illustrious as Swenson from the race to get the rule changed.

After I catch a few winks while my perspiration-soaked parka and heavy bib dry out, it’s mid-afternoon and time to go. I know the first couple of hours on the trail will be warmer than I’d like, but I have to get on to Finger Lake, 45 miles up the trail. I should get there late this evening and then I can wait a few hours so I can have some daylight for the always-harrowing run down to the un-aptly named Happy River.

I clean up around the sled, pack everything in (still too much), and start to bootie up the dogs. The temperature is so warm I don’t need to bootie everyone, only the ones with existing foot problems or historically vulnerable feet. Some mushers bootie every dog every step of the way but most are like me, only bootying as necessary. The process still takes half an hour, but I consider it time well spent because it keeps me close to the dogs on a one-on-one basis.

Читать дальше