Since I drew number 50 out of 61 this year, I’ll start 49th. This is because there are only 60 teams — the number one bib in the race, and the first starting position, is honorary. The parking spots are arranged in reverse order so the trucks of teams already started can drive off without interfering with teams waiting to go. This means my spot is near the front and every team before me passes by on its way to the start a block away.

It’s quite a fashion show. I’m still amazed by the money some of the frontline kennels put into their teams, with color-coordinated harnesses and sled bags and musher outfits. Some of the handler crews are uniformed like Olympic squads, especially those sponsored by outdoor-gear companies. And the sleds are technological wonders, some with fancy seats and special handlebars and more gadgets than James Bond’s trusty Aston-Martin (or is it a Beamer he’s driving now?).

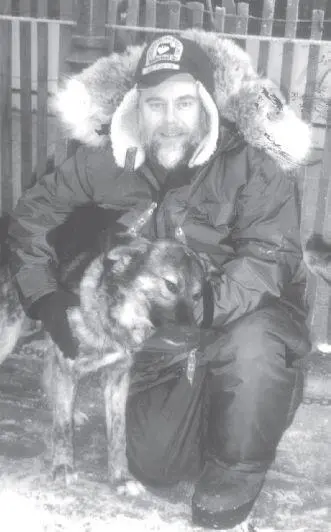

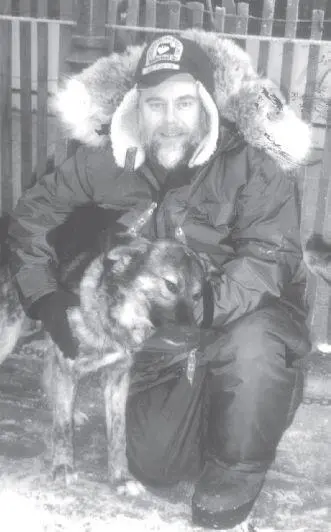

The author at the start of the Iditarod with Silvertip, his former personal pet and accidental sled dog who is mostly wolf. Wolves have long been out of favor as sled dogs and Silvertip is a throwback to the early days of the century when mushers sometimes ran wolf hybrids or even full-blooded wolves in their teams.

For low-budget drivers like me and Steve Adkins and John Barron, things are a lot simpler, and I’m not so sure I don’t like it that way. My harnesses are off the rack at the local musher supply store, my handlers are friends in jeans, and my sled is a standard Bernie Willis model, solid quality but far from the dream machines gliding by. My sled bag matches my slightly-the-worse-for-wear cold-weather gear, mainly because Bernie’s wife found a matching piece of fabric when she made it.

Soon enough the bib numbers passing by creep into the 40s and we get the dogs out of the boxes and harnessed up. The teams are starting at two-minute intervals, with every fifth team waiting three minutes to allow a television commercial break. Hooking up goes smoothly and before I realize it we’re in the grand parade up to the banner marking the starting chute. People I haven’t seen for years shout encouragement from the crowd, to which I weakly wave back and put on my best smile.

Now it’s my turn. The team is lined out smartly with old veteran Socks up front; I’m not taking any chances about going over the berm and into the crowd this year. I dimly register the one-minute warning, then suddenly it’s 15 seconds, then the final five-second countdown. The starter shouts “Go!” I yell “Okay!” and the team leaps away from the starting line with as much energy as any of the Big Names. No dives over the berm, no hesitations — we’re well and truly off and running like we know what we’re doing. I take it as a good omen.

A full 16-dog team Iditarod team is an incredibly powerful pulling machine. In some cases, each dog has its own holder for the stop-and-go procession to the starting line.

With Kim on the second sled and Idita-Rider Nancy Bee in mine (I keep thinking she’s from Sacramento), we make steady progress out of downtown Anchorage and onto the network of bike trails which become ski and dog trails in the winter. The only hitch is a new stretch of trail about five miles out, where the downhill curbs have been obliterated by the dozens of teams in front of me. I see the sled is going to slide off the trail as we cut across a corner. I warn Nancy to hang on but we dump despite my best efforts to keep everything upright; sleds just don’t maneuver well with people in them. We crunch against a tree and she takes some of the impact. She says she hurts a bit, but all I can do is try to joke with her and point out mushing is sometimes a contact sport as we pull back onto the trail and push on.

A few miles later, after a storybook run through the snow-covered birch forest, we stop to let Nancy out at the pickup station; she’s forgotten her bruises and has apparently enjoyed the trip. She says she’d love to go on to Eagle River, but I’m worried the extra load in the afternoon heat would prove too much for only 12 dogs. Besides, I know there are some bad stretches ahead and I’m worried another crash might sink the entire Idita-Rider program.

Kim and I press on. She wants to run the Iditarod in 1998, as soon as she’s eligible, and probably with some of these same dogs. This is a preview for her and I tell her by the time we unhook the second sled in Knik tomorrow she’ll already have run a good chunk of the race.

After a couple of hours of sun-slowed running and the usual spots of awful trail and another sled spill or two, we pull up the final hill into the Eagle River VFW post that has been the first checkpoint since the race’s inception. The dogs are in superb shape and this has actually been a good warm-up run for them.

After we get them all cooled off and fed and into the boxes I wander inside for the traditional bowl of moose stew and cornbread. As I eat I’m tired and still filled with uncertainty. Nome is more than 1,100 miles away and this hasn’t been any kind of an indicator of what things will be like out on the trail a week or 10 days from now.

For a moment I consider packing it all in and letting go of the Iditarod. I wouldn’t be the first person to do so. Then I realize that’s not an option. I have to do this race if I want to live with myself. Finishing it is probably the most important thing I’ll ever do. It has become a Holy Grail for me, a pilgrimage I can no longer explain to anyone, and maybe not even to myself. With a sigh I finish a last cup of Tang and head out to the truck. I’ll need all the sleep I can get before the restart tomorrow — the real beginning of my long-delayed trip to Nome.

March 3, 1996—The Iditarod: Wasilla to Knik (15 miles); Knik to Yentna Station (50 miles)

We’re in the procession of teams creeping toward the restart on the old Wasilla airport with steady old Socks in lead. The day is already hot and clear, just what I didn’t need. I wish we could have some 30-below Klondike 300 weather so the dogs can feel comfortable.

My back-in-the-pack start means it’s almost noon, with the heat of the day soon to come. The first teams are already 25 miles down the trail; they’ll run until mid-afternoon or so and then pull over and rest in the shade. I’ll still be plugging along, making slow time on the wiped-out trail. This is a disadvantage of a late draw, compounded by my slow team. The best I can expect is an average eight miles an hour, as opposed to the 10 or 12 of the better teams.

We start in the same order and at the same times as yesterday in Anchorage. The starting time differential will be evened up on the 24-hour layover, but in the meantime I’m starting out behind the power curve. Unfortunately, my dogs have trained in cold weather and have heavy coats. This means I just can’t run them as fast or as long as I’d like in balmy weather like this.

Some mushers have begun breeding for dogs with thinner coats, on the theory you can always put a coat on a cold dog, but you don’t have many options to cool off a thick-coated canine. I can already see I’ll have to go to a night-running schedule quickly, but today I have no choice but to slug it out as best I can.

The author’s team erupts from the starting chute at the Wasilla restart of the 1996 Iditarod. Socks and Maybelline are leading. The next stop is Knik, 14 miles away, where the second sled (ridden by Kim Hanson) will be dropped.

Читать дальше