I can use the brakes to suggest to them to restrain themselves going down steep hills or around the sharpest curves, but everything else depends on my ability to talk to them, to communicate with them on a much more direct level. If I don’t have the dogs’ trust, if they won’t listen to me when I tell them to gee or haw or whoa up, I’m not much more than an unwilling passenger on Mister Toad’s Wild Ride.

This is a partnership in every sense of the word, and it demands much from all involved. The team is a finely tuned machine, a thinking organism that can operate with a will of its own. Its individual components require my support for food and training and maintenance, but once assembled and in motion, it is a creature of a very much higher order whose total greatly exceeds the sum of its parts. If I’m very good, I will learn how to become part of the brain of this magnificent entity and thus make it whole.

It’s a sobering experience, but also profoundly satisfying and exhilarating. I may finally be starting to understand how mushers become so completely hooked, and why one-time Iditarod runners are a distinct minority in the Official Finisher’s Club.

October 10, 1994

Montana Creek, Alaska

As the dogs get back into shape in the fall, they expend prodigious amounts of energy. Without a healthy diet to provide the necessary calories and vitamins, all of our training would be meaningless, if not impossible. Therefore, we feed our dogs only the best.

Indeed, we cook for them, which not many mushers do any more. It’s more work, but the result is cheaper, more nutritious, and more appetizing (to the dogs). Even by human standards it would probably provide excellent nourishment, and might even be appealing if it weren’t for the inevitable smell from using fish guts and beef innards.

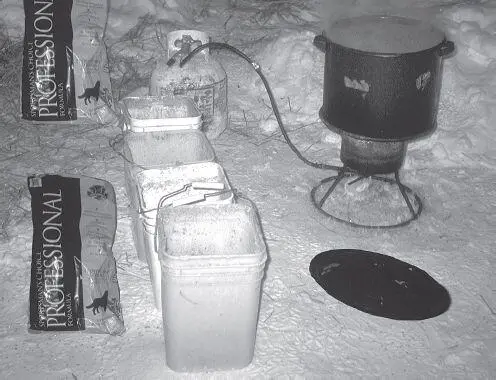

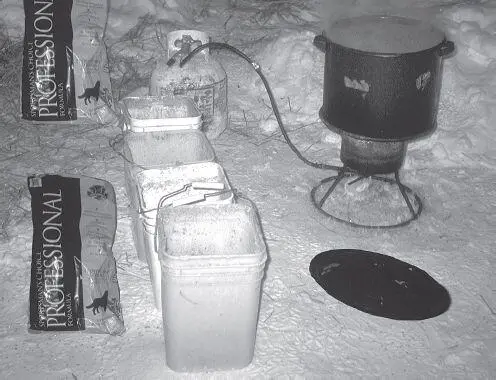

The vehicle for this culinary venture is a so-called Yukon cooker, which is a 55-gallon drum cut in half. A fire of spruce and birch is put in the bottom half (we’ll use a big propane burner later on in the winter) while the upper portion is inverted to hold maybe 25 gallons of food. The meat or fish is cooked first with water to make a steaming soup. As weather turns colder, additional fat goes into the mix to fuel the dogs’ runaway metabolic furnaces, and it forms a rich gravy whose aroma carries all through the dog yard. When the meat and fat are cooked, rice is added as a filler. Rice absorbs several times its volume in water and turns the meat soup into a thick stew.

One cooker load will yield a day’s food for 100 dogs. An hour or two before serving, dry dog food is added to the mix along with more water. The dog-food nuggets provide needed vitamins and absorb still more moisture. The result is a sort of pilaf of meat chunks, fat, rice, and commercial dog food which the dogs find irresistible. (Of course, they also find popcorn, tree roots, old bones, road kill, and even their own harnesses irresistible at times.)

The finished product contains a high water content. This is critical because some dogs won’t drink enough on their own to prevent dehydration when they’re working. This will be especially important on the race, where it will be necessary to ensure they take in water. By eating this moist food, they build good eating habits for the trail.

We’re feeding about 2,000 calories per dog per day, and that will go way up for the 60 or so first-string dogs we’ll start to focus on by the end of November. The folks at Costco and Sam’s already recognize me as a regular; I’m in there every few weeks for a quarter-ton of rice and several jumbo-size boxes of dog biscuits. Ron hits one of the feed stores back down the highway for a dozen, 40-pound bags of high-grade dog food on about the same schedule.

Ron also makes periodic trips to the slaughterhouse at Palmer. Their unfit-for-human-consumption by-products are perfect for the dogs and cook up very well. An average trip to the abattoir will yield half a dozen 60-pound boxes of the kind of stuff you usually find only in hot dogs. Occasionally we’ll also get the results of a freezer cleanout or maybe even the leavings from somebody’s yearly moose. (Moose remnants are especially good — the dogs can gnaw contentedly for weeks on the huge bones.) No matter. It all gets sliced up and tossed into the cooker and it all comes out looking the same. I’ve learned protein and fat come in many different forms and the dogs don’t care a bit.

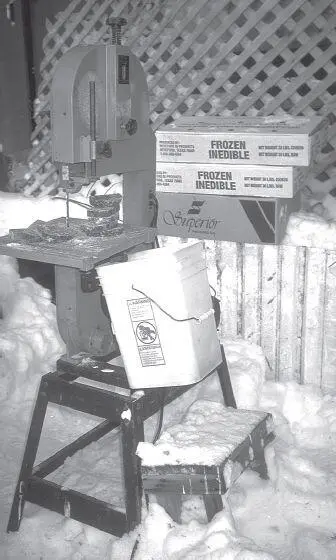

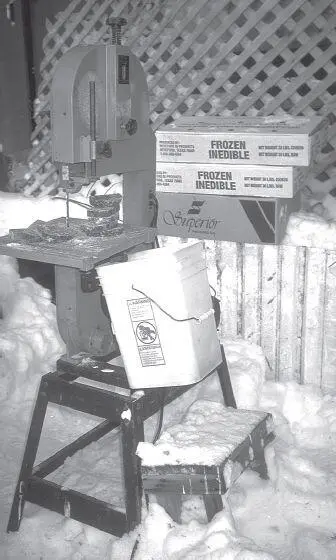

Many mushers operate do-it-yourself butcher shops to feed their dog lots. Ordinary band saws make excellent meat slicers, but electric circular saws, recipro saws, and even axes work just as well. Most mushers buy frozen meat in blocks of up to 50 pounds to supplement their commercial food, and this must all be reduced to dog-sized pieces. In preparation for the Iditarod, mushers have to slice up as much as half a ton of frozen meat.

Feeding time in the dog yard is an explosion of happy frenzy. The dogs can sense we mean to feed them, even if we make no overt move to do so. They must make a complex association between time of day, elapsed time since last feeding, smell of food in the cooking barrel, and our subtle but unintentional body language. For all I know, they may read our minds as well. I wouldn’t put it past them.

We often feed at night since we don’t like to run them on a full stomach. Besides, we want them to understand finishing a run means food, and they seem to appreciate this cause-and-effect relationship. If the dogs think the time is right, all we have to do is walk toward the cooling cooker and a chorus of barks and yelps and yips and howls instantly erupts. Ron’s dogs will even key on the creaking of his front door, which they must hear from 200 yards away.

As soon as we reappear with buckets of food in hand, the canine concert rises to a crescendo. Every dog has his or her own excited way of greeting us. At night, of course, the dancing, glowing eyes are all focused on us. They all want to be first. Little Penny at the far end of the line bounces at the end of her chain like a crazed popcorn kernel. Pullman hops up and down on a stump next to her house and barks as loudly as a dog three times her size.

Feeding time in the dog yard borders on pandemonium. The pups are especially frantic, since they don’t yet understand they all will get their share sooner or later.

Bear, whose demonic red-reflecting eyes belie his affectionate, playful nature, crouches like a tightly coiled spring with forelegs spread, ready to leap. His brother Chewy has the same eyes and frantically friendly disposition but his shorter legs give him the appearance of a demented bulldog; he is barely a blur as he races back and forth. Silvertip, my personal pet (and surprisingly good sled dog) who is three-quarters wolf, stands on his hind legs at the end of his chain and jumps two feet straight into the air, turning a flip and coming down facing the opposite direction, barking and yipping all the while.

Demure Blues hardly moves, carefully watching everything and giving only an occasional ladylike bark. Her half-sister Bea sounds like a siren and looks like a dervish as she circles her post. Socks, the wise old veteran who knows he is The Lead Dog, takes a watchful but silent stance. And pups on the outskirts keep up a chaotic racket; they don’t yet understand they will all eventually get fed and still treat feeding time as a live-or-die, zero-sum contest.

Some mushers cook for their dogs when they are at home. Big propane crab cookers are the weapon of choice, although wood-fired “Yukon cookers” made from 55-gallon drums work just as well. Ingredients include commercial dog food, fish, frozen meat, meat scraps, rice, fat, and anything else the dogs might eat. Cooking is an especially good way to safely use waste meat and wild game such as caribou which might harbor parasites.

Читать дальше