I’m not planning to get married out on the trail, but this is the kind of thing that has drawn me ever closer to the race over the years. I’ve heard people say the mushing community can be a tight-knit one, almost a big family. What I’ve seen today certainly hasn’t done anything to disprove this theory.

July 20, 1994

Montana Creek, Alaska

Ron and I now agree we can’t pull this off by ourselves. I must begin student teaching in a few more weeks at Mount Spurr Elementary in Anchorage in order to finish up my Master of Arts in Teaching. Since the dogs are a two-hour drive north at Montana Creek, I’ll only be able to run them on weekends and holidays, if then. Ron originally thought he could help me out by running my dogs during the week, but we both realize it’s not feasible.

Ron put out the word on the musher grapevine a few days ago we might need a live-in dog handler. Earlier today the solution to our problem drove up in a battered Chevy pickup. Twenty-year-old Barrie Raper has worked in dog lots in the Big Lake area for a couple of years. She knows Martin Buser and other mushing luminaries and she even has a team of her own.

In fact, she began mushing dogs in Wyoming in her early teens. After high school, she headed north with 15 hand-me-down dogs, a beat-up pickup truck, and her parents’ blessings. Her goal was Alaska and ultimately the Iditarod. Now she will help us in return for a place to live and help in running her own dogs.

Ron has an old cabin on his 120-acre property Barrie can use, and Ron and I commit to food for her dogs as well as some spending money. We also agree to pay her entry fees in some of the local races like the Knik 200. There is no mention of her running the Iditarod, but Ron and I secretly agree to help her enter the race this fall if things work out.

So now we have what amounts to a co-op kennel, with all three of us planning to run the Iditarod, even if one of us doesn’t know it yet. Ron and I understand we’ll be operating on the thinnest of shoestrings, but there’s nowhere to go but onward. I think to myself the adventure has truly begun, and now I’m going to be like every other musher I’ve ever met: permanently broke.

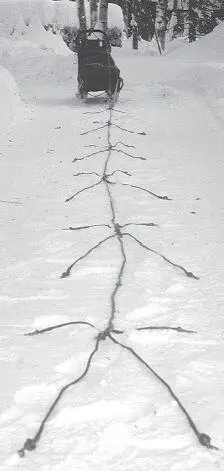

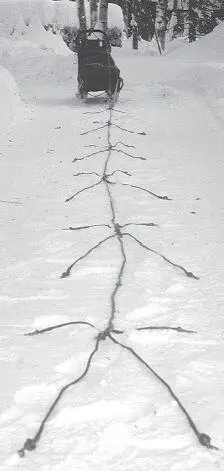

Dogs are hooked up in tandem in front of the sled. The central gangline has a core of aircraft cable and is made in two-dog sections 8 to 10 feet long that can be linked together for any number of dogs. Each dog is attached to the gangline by a tugline at the rear of its harness and by a thin neckline attached to its collar. There is no gangline for the leaders — their tuglines are attached to the previous section, and they are hooked together by a double-ended neckline called a doubler. There are no reins or lines connecting the leaders to the driver — the musher controls the team by voice commands only.

August 15, 1994

Montana Creek, Alaska

There are no shortcuts to the City of the Golden Beaches. The dogs require months of training, beginning well before the first snowflakes fall. Ron estimates we’ll need to put at least 1,000 miles on the dogs before the Iditarod, preferably more. So, the sooner we start, the better.

We’ve been running our teams for a couple of weeks with ATVs on unpaved local borough roads. (Alaska has boroughs, not counties.) This early in the season the runs are very short, only three or four miles long, and serve mainly to get the dogs back into the swing of things after their summer layoff.

The ATVs provide excellent training and the gravel toughens the dogs’ feet, but we must be very careful not to overheat the dogs in the late-summer warmth. We don’t even consider hooking up unless it’s raining or the temperature is below 60 degrees. Naturally, many of our runs are early in the morning or late at night, which greatly amuses our neighbors and the inevitable tourists.

My conveyance for these snowless safaris has so far been a beat-up three-wheeler I got really cheap earlier this summer. My first few excursions were sufficient to reveal why the machine’s previous owner didn’t ask more for it. On my first run, I hooked up half a dozen dogs and careened out onto the trail not knowing quite what to expect. I met approximately the same fate as a raw graduate of a driving school on a Los Angeles freeway.

I quickly discovered the thing is about as stable as a greased unicycle. Moreover, it’s not heavy enough to seriously impede the dogs when they’re in the “go” mode. Even six of them were more than powerful enough to overpower it, capsizing it on the first sharp turn and dragging it 25 yards while I observed helplessly from my sudden perch in the trail-side bushes.

Now I look on the infernal contraption with the same regard as a Bangkok pedicab I once tried to drive after knocking off a bottle of Thai whiskey. Luckily, I’ve managed to convince Bert to loan us a couple of four-wheelers, which are much less likely to assume the inverted position with no prior notice.

Anyway, another use for the ATVs is to establish the dogs’ speed. We help them with the engine until they start to lope and then try to hold them to the fastest possible trot. Loping is faster, but the dogs use more energy. The accepted method to master the endless miles of the Iditarod is a steady, energy-conserving trot, and the art is to set the trotting speed as high as possible. While we might accustom our dogs to trot a steady 10 miles an hour or so, the fast movers like Martin Buser get their number-one teams to trot at 14 or 15.

Speed isn’t really necessary for back-of-the-packers like us. Our dogs aren’t world-class trotters, but they’ll get us to Nome if we can keep everything else intact.

Dog trucks are among mushers’ most important pieces of equipment. They can vary from aging pickups with homemade plywood dog boxes on the back to professionally constructed heavy-duty machines. Dogs can be hooked to chains hung around the truck at races or for enroute stops. Regardless of size or cost, the truck has room for dogs, sleds, and all of the miscellaneous gear necessary to take a dog team on the road.

September 25, 1994

Mount Spurr Elementary Anchorage, Alaska

I’ve been student teaching for about a month, about the same time we’ve been seriously working the dogs. I’m finding it’s not always possible to completely separate the two activities.

In fact, I often can’t tell much difference between my class of 31 third and fourth graders and my dog team. Occasionally I even catch myself admonishing a boisterous kid as if he (or she) were one of my recalcitrant dogs: “Eddie, Sit!” On the other hand, I wonder on weekends if the dogs haven’t learned the kids’ tricks when they tangle up and generally act like jerks.

The kids, of course, are nuts about my dogs and my participation in the Iditarod. Our first read-aloud book of the semester is Gary Paulsen’s Woodsong , his young-adult version of his preparations to run the 1983 Iditarod. (According to the principal, Paulsen has visited our school more than once; indeed, the school library has virtually a complete autographed set of his books.)

There’s only one problem with a book like Woodsong —some of the passages are so emotional I have to stop reading aloud in mid-sentence and regain my composure, to the kids’ great consternation. They can’t understand how strongly I’m becoming attached to my own dogs, and the events Paulsen describes sometimes strike painfully close to home. Fortunately, my host teacher sympathizes, even if he often has the same problem I do. Only half-joking, he tells me our next book to read will be Where the Red Fern Grows ; I respond he’d better find somebody else to help him read the last couple of chapters, because I’ll break down completely.

Читать дальше