We plodded on, tacking back and forth to maintain our course, Bill in pain and I irritable, disappointed with our progress. We had hoped to make Horta in twelve days; now two weeks had passed. We worried that Gypsy Moth had already left Horta to return to England. We had hoped Bill would be able to return on her, saving the airfare.

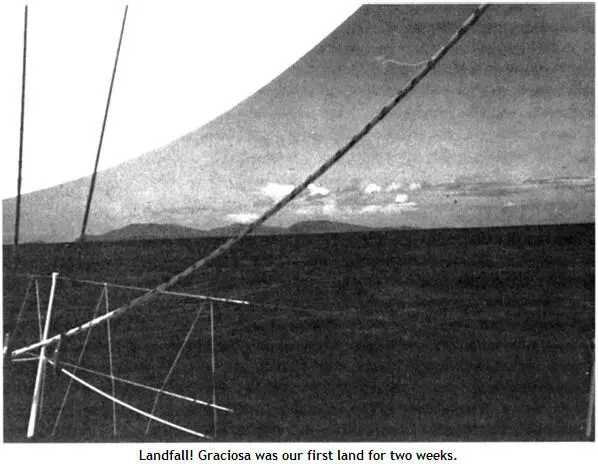

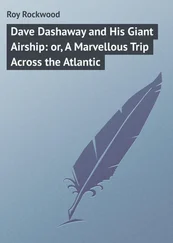

Finally, on Sunday morning, we awoke to find Graciosa, the first of the Azorean archipelago islands, on our route, sitting fat and green in our path. Even more remarkable, we had been freed again and were pointing at the port end of the island, right where we wanted to go, with the wind on our beam. We sailed on toward the island, and as we approached, a small motor launch appeared, towing two large rowboats full of men. Up a stubby mast on the launch, a man was clinging precariously, scanning the horizon. These were the Azorean whale hunters, going after the monster sea mammals as generations of Azoreans have, in an open boat, using a hand-thrown harpoon, their only concession to modernity the little launch which towed them out for their hunt. They gave us a cheerful wave and continued their search.

Then, of course, we were headed again and found ourselves pointing at the wrong end of the island, hard on the wind. Graciosa looked very inviting, with thick, green vegetation; tiny, white villages here and there; and beautiful beaches, with an occasional stretch of dramatic cliffs. We beat our way into the channel between Graciosa and St. Jorge, the neighboring island, and pressed on toward Horta in the shallower, rougher water and freshening winds. We beat all day and all night. I contrived not to wake Bill until he had got some sleep and then turned in at dawn. Sunrise was a relief, for we had been running without lights. About a week out, the Marinaspec masthead light had inexplicably stopped working, and two days before, our spare navigation lights had gone, too. We then ran with the deck lights on, which took a lot of battery charging but at least made us visible. Finally, the deck lights went, too, and our last night out we were completely dark and worried about the possibility of colliding with an unlit fishing boat in the blackness.

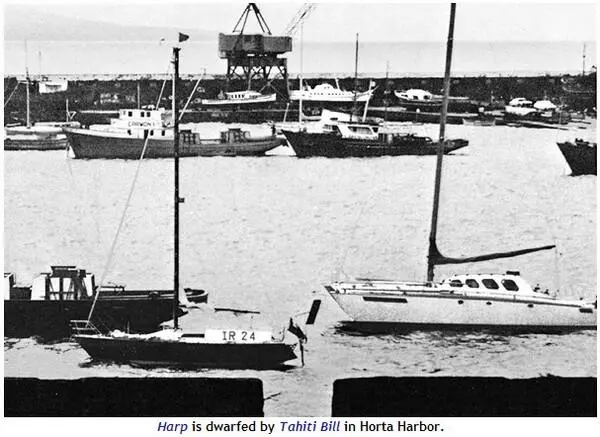

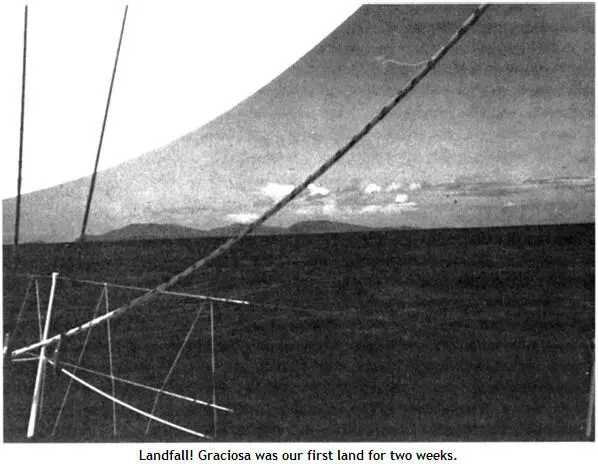

At half past seven Bill woke me. I looked across the water and saw the harbor wall of Horta. We put in a final tack and crossed the finishing line at 08.47, local time. We sailed into the harbor and were directed to a mooring. Somebody on shore set off some fireworks. As we furled the reefing genoa the Dynafurl broke again, but it didn’t seem to matter now. We were in Horta. It had taken us fifteen and a half days.

What we saw amazed me. I had been expecting a brown, arid, rather deserted island. Faial was as lush and green as Ireland, and more mountainous. Horta wrapped around the little harbor and ran up the hillside, lots of trees and white buildings.

Gypsy Moth V was moored nearby. Giles Chichester rowed over and invited us aboard for coffee. We began to pump up the dinghy. A motorboat came alongside and deposited a plump fellow in a bright green shirt aboard, waving customs forms. Funny sort of customs man, I thought. He extended a hand and said, in American-accented English, “Hi, I’m Augie.” And Augie he was. Born of an American mother and an Azorean father, August (pronounced “Ow-goost”) had spent some time in California before returning to live in Horta. Augie was a mine of information and good cheer. Did the laundry need doing? No problem. The electrics need fixing? Can do. I really began to relax. We signed the forms, surrendered our passports to Augie, and splashed over to Gypsy Moth . There Giles and his crew, Martin Wolford, brought us up to date. Runnin’ Scared had won the race. We were the last boat to finish, though not last on corrected time (we were also the smallest boat to finish), and three or four boats had retired. Everybody had taken longer than anticipated, so the dinner had been put back to Sunday night. We had missed it by twelve hours. But there was a beach party that night, and probably one every night from now on. The Club Naval, the local yachting, diving, swimming, and fishing organization, had apparently been given a grant from the government tourist office to entertain the race crews and their wives and girlfriends who had met them in Horta, and the club was having a wonderful time spending it. Nobody’s feet had touched ground since reaching Horta. Neither would ours.

We staggered ashore under the weight of an incredible amount of laundry for two people, borrowed the staff shower at the Estalagem de Santa Cruz, a lovely modern hotel built inside the walls of an old fort next to the Club Naval, then, cleaner and more closely shaven than we would have dreamed possible, tucked into a lunch of fresh tuna (I had always thought they were born in cans) fried in batter, local grapes and cheese, and a cold bottle of the native white wine, Pico Branco (the local red wine is good, too, if you don’t mind your teeth turning blue), all of it a welcome change from the tinned food on the boat.

Thus fortified, we began to lurch about Horta, exploring. We lurched because we had not yet got back our land legs, and the earth seemed to move in the same way the boat had. We found the Café Sport, which is the headquarters for visiting yachtsmen in Horta. The owner, Peter, receives and forwards mail, changes money, lends his telephone, and keeps social intercourse among visiting boats moving at a brisk pace. We renewed acquaintance with other crews over cold beer at the Club Naval and swapped stories about our experiences on the passage out. As it turned out, nearly all the other boats had sailed into a different weather system from the one we had encountered, and while we had had fresh headwinds for virtually the whole passage, they had had free but light winds and had suffered calms, so everyone had been slow arriving.

I got a list of finishing times, did some calculating, and discovered to my astonishment that, allowing for the eleven hours required to put Shirley ashore, we had finished third on handicap, beating Gypsy Moth on corrected time. In fact, only Runnin’ Scared and Triple Arrow had beaten us on handicap. But, in spite of our appeal to the committee, we had been disqualified under the three-man, minimum-crew rule, as had been David Palmer, in FT, who had put a crew ashore on another island so that he could make a flight back to England. Our good position on corrected time raised my hopes for the handicap prize in the OSTAR, but much would depend on the kind of handicap I would be assigned for that race.

In the afternoon I completely succumbed to the lure of being ashore again and moved into the Estalagem de Santa Cruz, reveling once more in clean sheets and hot showers. The boat was a bit of a mess, anyway, since she had begun taking water through the keelbolts again, and everything was very damp. All the rooms had balconies overlooking the harbor, and I could see Harp bobbing gently at her moorings, only a couple of hundred yards away. Bill moved into a hotel on top of the hill and got some much-needed rest.

That evening Club Naval threw a beach party for us and, leaning into twenty-knot winds, we ate fish rubbed with garlic and cooked over a charcoal fire, washed down with Pico Branco. Lots of locals and nearly all of the crews came, and all had a marvelous time.

For the next day or so I wandered around dazed, still unable to believe that I was actually in Horta. Giles Chichester threw a party on Gypsy Moth, and two other boats were tied alongside to handle the overflow. The conversation and the wine flowed like water, and before we knew it late evening had come and all of Horta’s restaurants were closed. Martin Wolford; John Perry, skipper of Peter, Peter, who floated about in a white suit, straw hat, and ten-day beard in the best beachcomber style and who claimed to be a solicitor in London; and a young lady who had flown out to meet a competitor who had subsequently retired from the race, all came to dinner on Golden Harp. We ate and drank well and when, in the wee small hours of the morning, the party began to break up and John and Martin offered to deliver the young lady ashore, I said I would do that myself, since I did not wish to disturb her while she was washing the dishes. I saw John and Martin on deck and to their respective dinghies and then settled down with a brandy while the young lady finished in the galley.

Читать дальше