Other communication systems were, however, working. One bright Sunday morning I awoke to find that, having left the reversing lamp on my car on all night, the battery was completely dead. Being some distance from a telephone, I had another idea. The VHF radio-telephone which I had bought at the London Boat Show was a self-contained one, having its own power supply. Technically, the radio was not supposed to be operated except on the yacht, and only after having been licensed. The boat did not even exist yet, and I had not even applied for a license, but I got out the list of Irish coastal stations and the instructions for transmission procedure. I studied them for a few minutes and then switched on the radio.

“Cobh Radio, Cobh Radio, Cobh Radio (the Cork Harbor station), this is Woodsmoke, Woodsmoke, Woodsmoke (a tentative name for the yacht). Do you read me?” Silence for two minutes, the instructions said. Then if no reply, try again. I tried again.

I jumped about a foot when a clear voice said, “Woodsmoke, Woodsmoke, Woodsmoke, this is Cobh Radio, Cobh Radio, Cobh Radio, what is your position? Over.”

“Cobh Radio, I’m at Drake’s Pool, uh, ashore, uh, and I have a problem with my car. I wonder if you could possibly telephone the AA for me? Over.”

Silence. He probably didn’t think he was hearing properly. Then he came back. “Woodsmoke, we don’t ordinarily do that sort of thing, but we’re not too busy right now, and I’ve been in that position myself. How will the AA find you? Over.”

“I’m at Drake’s Pool Cottage...”

“Cottage!” he interrupted. After all, this was supposed to be a ship-to-shore radio.

“Ah, yes, there’s this cottage, and my car is parked there.” I gave him the complicated directions for finding me and we signed off.

An hour later an AA man appeared, scratching his head and saying that he’d never had a call like this one before. I had half expected the police, but a minute or two later the car was started. I never used the VHF ashore again, though.

The Dublin Boat Show rolled around, and I used the trip to Dublin to check on what was happening with The Irish Times. Nothing, apparently. However, Exide had agreed to donate the batteries for the boat. It was the first equipment I had been given, and was a lift to the spirits. The Dublin show seemed small after the London one, but it was interesting, and I bought an outboard motor for the dinghy and a few small things.

Back at Southcoast, the first deck went onto the first hull of the new series. It was the first glimpse I had of anything like the complete boat, and I was impressed with what a pretty craft she was going to be. The first and third boats in the series were being sent out unfinished, in kit form, but the second boat, a bright red one which would be finished in the factory, was getting under way, and I was looking forward to seeing it take shape.

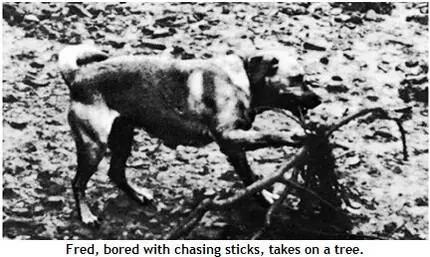

Then Fred vanished. He was grown now but still very much the puppy at heart, and he missed the dogs and children at Lough Cutra, especially the children. He had taken to walking the mile or so to the main gate of Coolmore, where a group of small kids gathered to play, and one night, he didn’t come home. To make matters worse, his collar and name tag had disappeared the day before, so nobody would know where he came from. As the days passed with no sign of him I took to driving around the countryside looking for him. He had been stolen twice as a puppy, but recovered, and I was increasingly worried about him. He was the only company I had in the cottage, and good company he was, always making me laugh, bringing me sticks to throw into the river for him to retrieve. He liked swimming better than walking, being a Labrador. I put notices up in the post offices in the surrounding villages. He was seen at Ringaskiddy, then Currabinny, then Douglas, eight miles away. There were apparently a lot of golden Labradors about. Since I didn’t have a phone, Ron was taking the calls, and they were coming in at the rate of two or three a day. I got one from Kanturk, twenty miles away, but it turned out to be a different Lab. Finally, I put an ad in the Cork Examiner, and someone in Douglas called. They had had a strange Labrador about for days. I went to Douglas. It was Fred. He had been gone for two weeks. The minute he was home he had a stick in his mouth, ready for his swim. He got a new collar and ID tag the same day.

9

Organize, organize, organize

In late March we had the second of our navigation classes in Galway, and I managed to get a lot into the weekend. I had dinner with Harry and Lorna McMahon, and although Bill King was away (skiing), his wife, Anita, joined us. What a delightful woman she is. We talked about her best-selling book, Jenny, based on the life of Winston Churchill’s mother. Anita’s grandmother was Jenny’s sister, and Anita had known Lady Randolph Churchill as a child. The television series based on the book was running at the time, and talk centered on that. She mentioned that Bill was looking forward eagerly to the Azores trip. I asked Harry to come as well, but he was doubtful whether he’d be able to manage the time. I had already invited Ewan Southby-Tailyour, but he wasn’t sure whether the Royal Marines would give him time to do the Azores race and the OSTAR in successive years.

Our navigation class went well, and we agreed to spend our final weekend, in April, cruising to the Aran Islands and back, putting our newfound knowledge into practice.

Back in Cork, it was time to place my order for sails, and John McWilliam and I sat down to discuss this. Getting John McWilliam to sit down is no small feat. He is the only person I met during the whole of my stay in Ireland who is visibly energetic about his work.

John McWilliam is a northerner, from the Six Counties, and after engineering school did a spell with the RAF, doing individual aerobatics with the famous Red Arrows stunt team at air shows. After that, he did an apprenticeship with the Australian sailmaker Rolly Tasker in his Hong Kong loft, then opened a Tasker branch in Ireland. By the time I arrived, he had gone out on his own, making his sails on the main floor of an old stone mill on the hill behind Crosshaven, and living in a handsome flat on the top floor.

Visiting the McWilliam Sailmakers loft is an experience. You can feel the glass vibrating before you even open the door, and inside, sound strikes with a physical force. There is a souped-up stereo system driving a series of huge speakers, and the noise which comes out is overpowering to all but the demented teenyboppers with whom John McWilliam shares his musical taste. Through two more sets of sliding doors and into the loft proper, one comes upon Mr. McWilliam, loping about the varnished floor, carpet slippers on his feet, foam rubber taped to his knees, with a grace of movement not seen since the actor known as Stepin Fetchit plied the silver screen. John moves much faster, though, and constantly.

John is also very bright, and a first-rate man on a racing yacht. He is probably the only one of the world’s top three or four sailmakers who still cuts every sail himself, assisted only by his right-hand man and a harem of local girls, who, even while bent over their sewing machines, giggle and blush constantly. John makes up for being in an out-of-the-way place by delivering his sails to customers all over the British Isles and Europe in a twin-engine Piper Apache, the flying of which gives him enormous pleasure. He probably gives his customers a more personal and more effective service than some sailmakers located in hotbeds of sailing activity, such as the south coast of England. He claims to charge less, too, and his sails are nearly as good as he says they are.

Читать дальше