“We’ll never get the car up that,” said Milo unhappily.

“True enough,” replied the Mathemagician, “but you can be in Ignorance quick enough without riding all the way; and if you’re to be successful, it will have to be step by step.”

“But I would like to take my gifts,” Milo insisted.

“So you shall,” announced the Dodecahedron, who appeared from nowhere with his arms full. “Here are your sights, here are your sounds, and here,” he said, handing Milo the last of them disdainfully, “are your words.”

“And, most important of all,” added the Mathemagician, “here is your own magic staff. Use it well and there is nothing it cannot do for you.”

He placed in Milo’s breast pocket a small gleaming pencil which, except for the size, was much like his own. Then, with a last word of encouragement, he and the Dodecahedron (who was simultaneously sobbing, frowning, pining, and sighing from four of his saddest faces) made their farewells and watched as the three tiny figures disappeared into the forbidding Mountains of Ignorance.

Almost immediately the light began to fade as the difficult path wandered aimlessly upward, inching forward almost as reluctantly as the trembling Humbug. Tock as usual led the way, sniffing ahead for danger, and Milo, his bag of precious possessions slung over one shoulder, followed silently and resolutely behind.

“Perhaps someone should stay back to guard the way,” said the unhappy bug, offering his services; but, since his suggestion was met with silence, he followed glumly along.

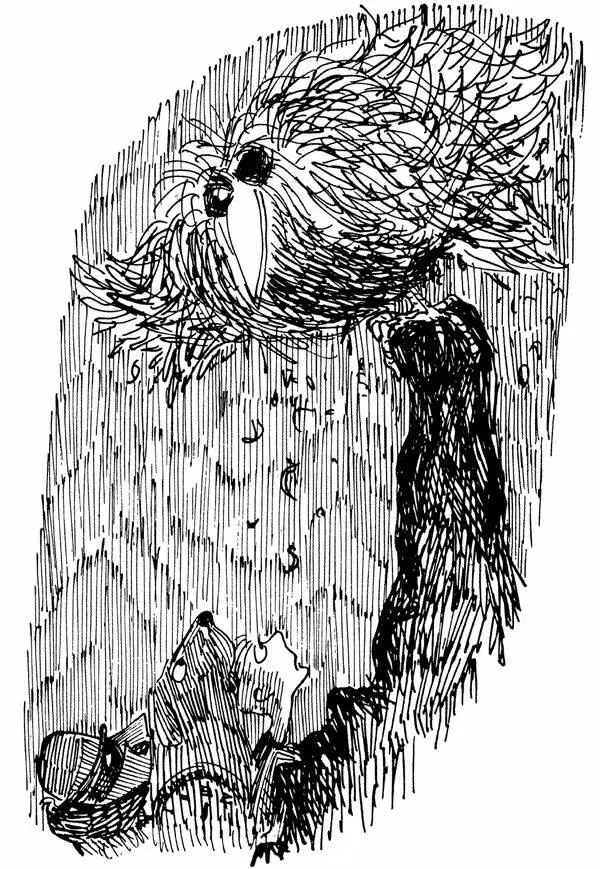

The higher they went, the darker it became, though it wasn’t the darkness of night, but rather more like a mixture of lurking shadows and evil intentions which oozed from the slimy moss-covered cliffs and blotted out the light. A cruel wind shrieked through the rocks and the air was thick and heavy, as if it had been used several times before.

On they went, higher and higher up the dizzying trail, on one side the sheer stone walls and brutal peaks towering above them, and on the other an endless, limitless, bottomless nothing.

“I can hardly see a thing,” said Milo, taking hold of Tock’s tail as a sticky mist engulfed the moon. “Perhaps we should wait until morning.”

“They’ll be mourning for you soon enough,” came a reply from directly above, and this was followed by a hideous cackling laugh very much like someone choking on a fishbone.

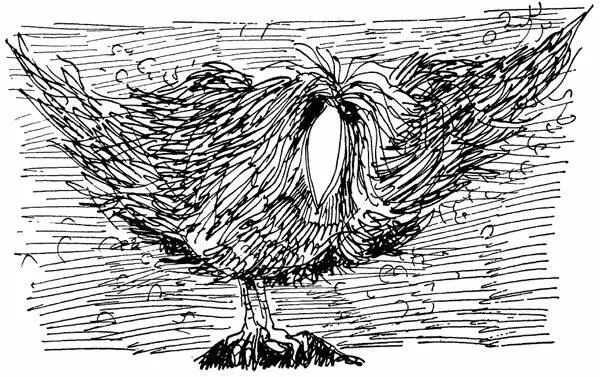

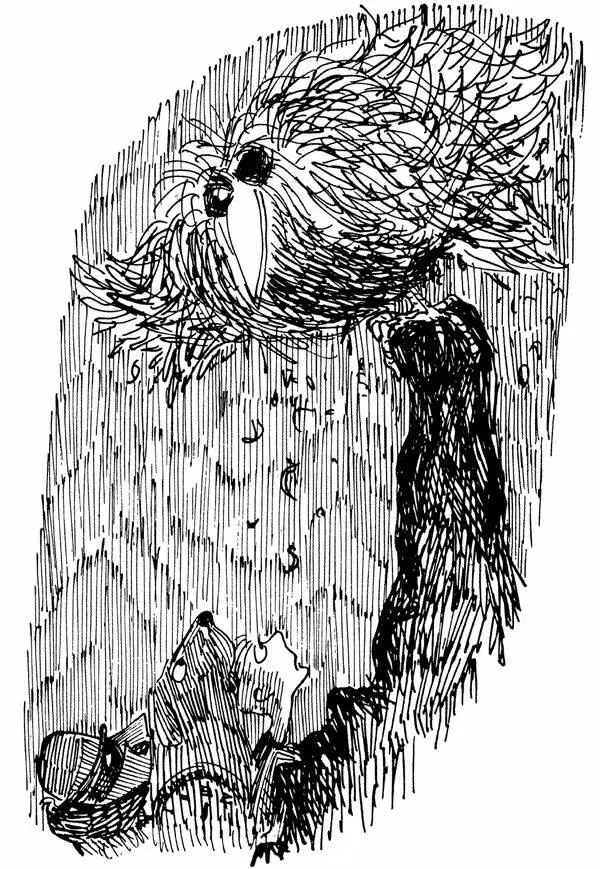

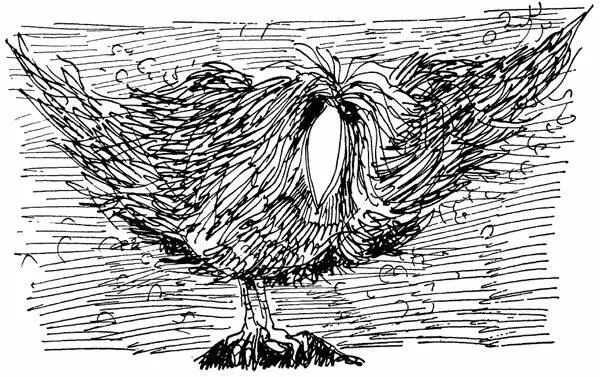

Clinging to one of the greasy rocks and blending almost perfectly with it was a large, unkempt, and exceedingly soiled bird who looked more like a dirty floor mop than anything else. He had a sharp, dangerous beak, and the one eye he chose to open stared down maliciously.

“I don’t think you understand,” said Milo timidly as the watchdog growled a warning. “We’re looking for a place to spend the night.”

“It’s not yours to spend,” the bird shrieked again, and followed it with the same horrible laugh.

“That doesn’t make any sense, you see——” he started to explain.

“Dollars or cents, it’s still not yours to spend,” the bird replied haughtily.

“But I didn’t mean——” insisted Milo.

“Of course you’re mean,” interrupted the bird, closing the eye that had been open and opening the one that had been closed. “Anyone who’d spend a night that doesn’t belong to him is very mean.”

“Well, I thought that by——” he tried again desperately.

“That’s a different story,” interjected the bird a bit more amiably. “If you want to buy, I’m sure I can arrange to sell, but with what you’re doing you’ll probably end up in a cell anyway.”

“That doesn’t seem right,” said Milo helplessly, for, with the bird taking everything the wrong way, he hardly knew what he was saying.

“Agreed,” said the bird, with a sharp click of his beak, “but neither is it left, although if I were you I would have left a long time ago.”

“Let me try once more,” Milo said in an effort to explain. “In other words——”

“You mean you have other words?” cried the bird happily. “Well, by all means, use them. You’re certainly not doing very well with the ones you have now.”

“Must you always interrupt like that?” said Tock irritably, for even he was becoming impatient.

“Naturally,” the bird cackled; “it’s my job. I take the words right out of your mouth. Haven’t we met before? I’m the Everpresent Wordsnatcher, and I’m sure I know your friend the bug.” And then he leaned all the way forward and gave a terrible knowing smile.

The Humbug, who was too big to hide and too frightened to move, denied everything.

“Is everyone who lives in Ignorance like you?” asked Milo.

“Much worse,” he said longingly. “But I don’t live here. I’m from a place very far away called Context.”

“Don’t you think you should be getting back?” suggested the bug, holding one arm up in front of him.

“What a horrible thought.” The bird shuddered. “It’s such an unpleasant place that I spend almost all my time out of it. Besides, what could be nicer than these grimy mountains?”

“Almost anything,” thought Milo as he pulled his collar up. And then he asked the bird, “Are you a demon?”

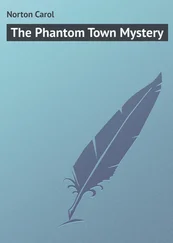

“I’m afraid not,” he replied sadly, as several filthy tears rolled down his beak. “I’ve tried, but the best I can manage to be is a nuisance,” and, before Milo could reply, he flapped his dingy wings and flew off in a cascade of dust and dirt and fuzz.

“Wait!” shouted Milo, who’d thought of many more questions he wanted to ask.

“Thirty-four pounds,” shrieked the bird as he disappeared into the fog.

“He was certainly no help,” said Milo after they had been walking again for some time.

“That’s why I drove him off,” cried the Humbug, fiercely brandishing his cane. “Now let’s find the demons.”

“That might be sooner than you think,” remarked Tock, looking back at the suddenly trembling bug; and the trail turned again and continued to climb.

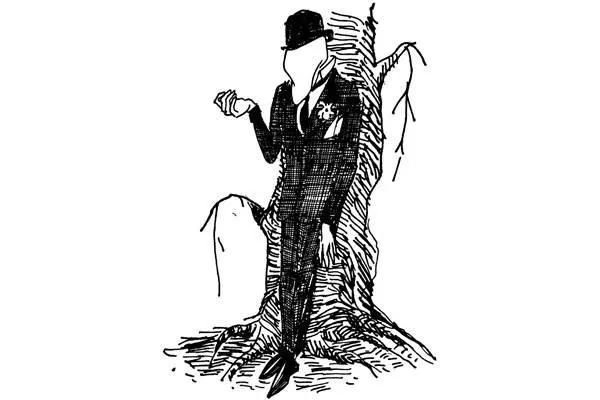

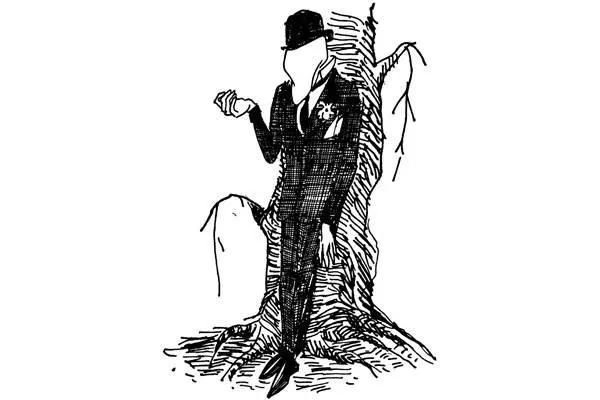

In a few minutes they’d reached the crest, only to find that beyond it lay another one even higher, and beyond that several more, whose tops were lost in the swirling darkness. For a short stretch the path became broad and flat, and just ahead, leaning comfortably against a dead tree, stood a very elegant-looking gentleman.

He was beautifully dressed in a dark suit with a well-pressed shirt and tie. His shoes were polished, his nails were clean, his hat was well brushed, and a white handkerchief adorned his breast pocket. But his expression was somewhat blank. In fact, it was completely blank, for he had neither eyes, nose, nor mouth.

“Hello, little boy,” he said, amiably shaking Milo by the hand. “And how’s the faithful dog?” he inquired, giving Tock three or four strong and friendly pats. “And who is this handsome creature?” he asked, tipping his hat to the very pleased Humbug. “I’m so happy to see you all.”

“What a pleasant surprise to meet someone so nice,” they all thought, “and especially here.”

“I wonder if you could spare me a little of your time,” he inquired politely, “and help with a few small jobs?”

Читать дальше