“Have you always been that way?” asked Milo impatiently, for he felt that that was a needlessly fine distinction.

“My goodness, no,” the child assured him. “A few years ago I was just .42 and, believe me, that was terribly inconvenient.”

“What is the rest of your family like?” said Milo, this time a bit more sympathetically.

“Oh, we’re just the average family,” he said thoughtfully; “mother, father, and 2.58 children—and, as I explained, I’m the .58.”

“It must be rather odd being only part of a person,” Milo remarked.

“Not at all,” said the child. “Every average family has 2.58 children, so I always have someone to play with. Besides, each family also has an average of 1.3 automobiles, and since I’m the only one who can drive three tenths of a car, I get to use it all the time.”

“But averages aren’t real,” objected Milo; “they’re just imaginary.”

“That may be so,” he agreed, “but they’re also very useful at times. For instance, if you didn’t have any money at all, but you happened to be with four other people who had ten dollars apiece, then you’d each have an average of eight dollars. Isn’t that right?”

“I guess so,” said Milo weakly.

“Well, think how much better off you’d be, just because of averages,” he explained convincingly. “And think of the poor farmer when it doesn’t rain all year: if there wasn’t an average yearly rainfall of 37 inches in this part of the country, all his crops would wither and die.”

It all sounded terribly confusing to Milo, for he had always had trouble in school with just this subject.

“There are still other advantages,” continued the child. “For instance, if one rat were cornered by nine cats, then, on the average, each cat would be 10 per cent rat and the rat would be 90 per cent cat. If you happened to be a rat, you can see how much nicer it would make things.”

“But that can never be,” said Milo, jumping to his feet.

“Don’t be too sure,” said the child patiently, “for one of the nicest things about mathematics, or anything else you might care to learn, is that many of the things which can never be, often are. You see,” he went on, “it’s very much like your trying to reach Infinity. You know that it’s there, but you just don’t know where—but just because you can never reach it doesn’t mean that it’s not worth looking for.”

“I hadn’t thought of it that way,” said Milo, starting down the stairs. “I think I’ll go back now.”

“A wise decision,” the child agreed; “but try again someday—perhaps you’ll get much closer.” And, as Milo waved good-by, he smiled warmly, which he usually did on the average of 47 times a day.

“Everyone here knows so much more than I do,” thought Milo as he leaped from step to step. “I’ll have to do a lot better if I’m going to rescue the princesses.”

In a few moments he’d reached the bottom again and burst into the workshop, where Tock and the Humbug were eagerly watching the Mathemagician perform.

“Ah, back already,” he cried, greeting him with a friendly wave. “I hope you found what you were looking for.”

“I’m afraid not,” admitted Milo. And then he added in a very discouraged tone, “Everything in Digitopolis is much too difficult for me.”

The Mathemagician nodded knowingly and stroked his chin several times. “You’ll find,” he remarked gently, “that the only thing you can do easily is be wrong, and that’s hardly worth the effort.”

Milo tried very hard to understand all the things he’d been told, and all the things he’d seen, and, as he spoke, one curious thing still bothered him. “Why is it,” he said quietly, “that quite often even the things which are correct just don’t seem to be right?”

A look of deep melancholy crossed the Mathemagician’s face and his eyes grew moist with sadness. Everything was silent, and it was several minutes before he was able to reply at all.

“How very true,” he sobbed, supporting himself on the staff. “It has been that way since Rhyme and Reason were banished.”

“Quite so,” began the Humbug. “I personally feel that——”

“AND ALL BECAUSE OF THAT STUBBORN WRETCH AZAZ,” roared the Mathemagician, completely overwhelming the bug, for now his sadness had changed to fury and he stalked about the room adding up anger and multiplying wrath. “IT’S ALL HIS FAULT.”

“Perhaps if you discussed it with him——” Milo started to say, but never had time to finish.

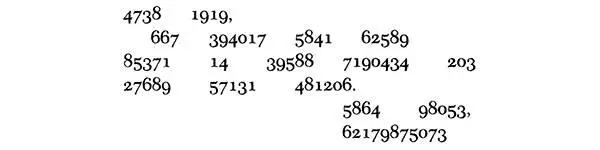

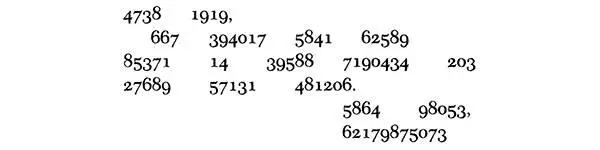

“He’s much too unreasonable,” interrupted the Mathemagician again. “Why, just last month I sent him a very friendly letter, which he never had the courtesy to answer. See for yourself.”

He handed Milo a copy of the letter, which read:

“But maybe he doesn’t understand numbers,” said Milo, who found it a little difficult to read himself.

“NONSENSE!” bellowed the Mathemagician. “Everyone understands numbers. No matter what language you speak, they always mean the same thing. A seven is a seven anywhere in the world.”

“My goodness,” thought Milo, “everybody is so terribly sensitive about the things they know best.”

“With your permission,” said Tock, changing the subject, “we’d like to rescue Rhyme and Reason.”

“Has Azaz agreed to it?” the Mathemagician inquired.

“Yes, sir,” the dog assured him.

“THEN I DON’T,” he thundered again, “for since they’ve been banished, we’ve never agreed on anything—and we never will.” He emphasized his last remark with a dark and ominous look.

“Never?” asked Milo, with the slightest touch of disbelief in his voice.

“NEVER!” he repeated. “And if you can prove otherwise, you have my permission to go.”

“Well,” said Milo, who had thought about this problem very carefully ever since leaving Dictionopolis. “Then with whatever Azaz agrees, you disagree.”

“Correct,” said the Mathemagician with a tolerant smile.

“And with whatever Azaz disagrees, you agree.”

“Also correct,” yawned the Mathemagician, nonchalantly cleaning his fingernails with the point of his staff.

“Then each of you agrees that he will disagree with whatever each of you agrees with,” said Milo triumphantly; “and if you both disagree with the same thing, then aren’t you really in agreement?”

“I’VE BEEN TRICKED!” cried the Mathemagician helplessly, for no matter how he figured, it still came out just that way.

“Splendid effort,” commented the Humbug jovially; “exactly the way I would have done it myself.”

“And now may we go?” added Tock.

The Mathemagician accepted his defeat with grace, nodded weakly, and then drew the three travelers to his side.

“It’s a long and dangerous journey,” he began softly, and a furrow of concern creased his forehead. “Long before you find them, the demons will know you’re there. Watch for them well,” he emphasized, “for when they appear, it might be too late.”

The Humbug shuddered down to his shoes, and Milo felt the tips of his fingers suddenly grow cold.

“But there is one problem even more serious than that,” he whispered ominously.

“What is it?” gasped Milo, who was not sure he really wanted to know.

“I’m afraid I can tell you only when you return. Come along,” said the Mathemagician, “and I’ll show you the way.” And, simply by carrying the three, he transported them all to the very edge of Digitopolis. Behind them lay all the kingdoms of Wisdom, and up ahead a narrow rutted path led toward the mountains and darkness.

Читать дальше