Norton Juster

The Phantom Tollbooth

To Andy and Kenny,

who waited so patiently

You know you’re in excellent hands when, in the midst of some nutty, didactic dialogue, the author disarms you.

“I guess I just wasn’t thinking ,” said Milo .

“PRECISELY,” shouted the dog as his alarm went off again. “Now you know what you must do .”

“I’m afraid I don’t,” admitted Milo, feeling quite stupid .

“Well,” continued the watchdog impatiently, “since you got here by not thinking, it seems reasonable to expect that, in order to get out, you must start thinking.” And with that he hopped into the car .

It’s what Tock, the literal watchdog (see the Feiffer illustration), says next that makes my heart melt, as it did on my very first reading way back when: “Do you mind if I get in? I love automobile rides.” There is the teeming-brained Norton Juster touching just the right note at just the right moment.

The Phantom Tollbooth leaps, soars, and abounds in right notes all over the place, as any proper masterpiece must. Early critics responded enthusiastically, garnishing their reviews with exuberant Justeresque puns and wordplay. Comparison with Alice in Wonderland was inevitable, “for the author displays a similar ingenuity, bite, and playfulness in his attack on the common usage of words.” All well and good—wonderful, in fact—this miracle of instant recognition by contemporary critics. And nice—lovely, even—to be compared to Alice , though I suspect Norton Juster would have preferred, if his book had to be compared, The Wind in the Willows . It was even compared to Bunyan! “As Pilgrim’s Progress is concerned with the awakening of the sluggardly spirit, The Phantom Tollbooth is concerned with the awakening of the lazy mind.”

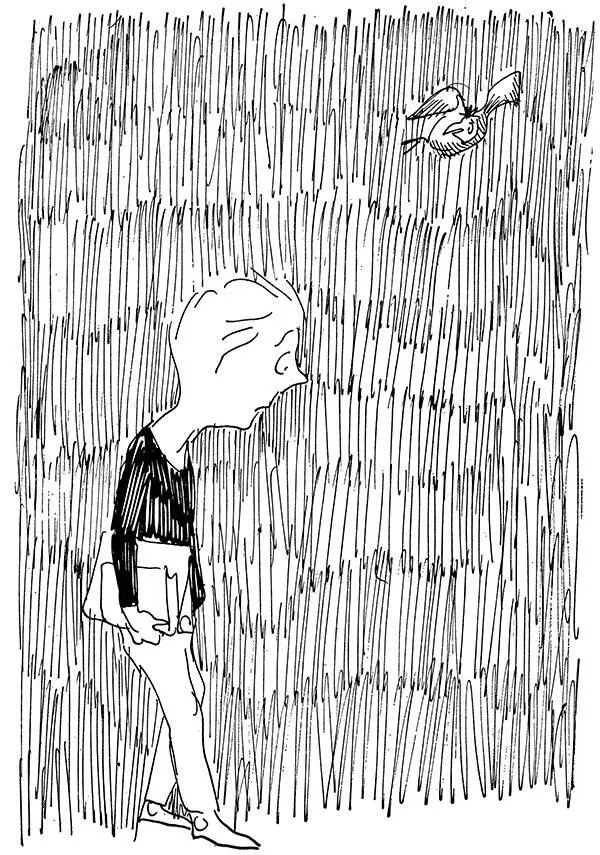

All of the above would gladden the heart of any young writer, but comparisons to Carroll and Bunyan only begin to suggest the qualities that make Tollbooth so splendid. For me, it is primarily the heart and soul of Norton Juster—his menschkeit—that produced this marvel of a book. Another part of the marvel: even though Tollbooth is extraordinary fantasy, it is tightly hinged in the here and now, and conveys an urgent and vivid sense of reality. Jules Feiffer—that rare artist who can draw an idea—combines the same insistent reality and uninhibited fantasy in his superb scratchy-itchy pen drawings.

Tollbooth is a product of a time and place that fills me with fierce nostalgia. It was published in New York City in 1961, that golden moment in American children’s book publishing when we lucky kids—Norton, Jules, myself, and many more—were all swept up in a publishing adventure full of risks and high jinks that has nearly faded from memory. There were no temptations except to astonish. There were no seductions because there was not much money, and “kiddie books” were firmly nailed to the bottom of the “literary-career totem pole.” Simply, it was easy to stay clean and fresh, and wildly ourselves—a pod of happy baby whales, flipping our lusty flukes and diving deep for gold. Tollbooth is pure gold.

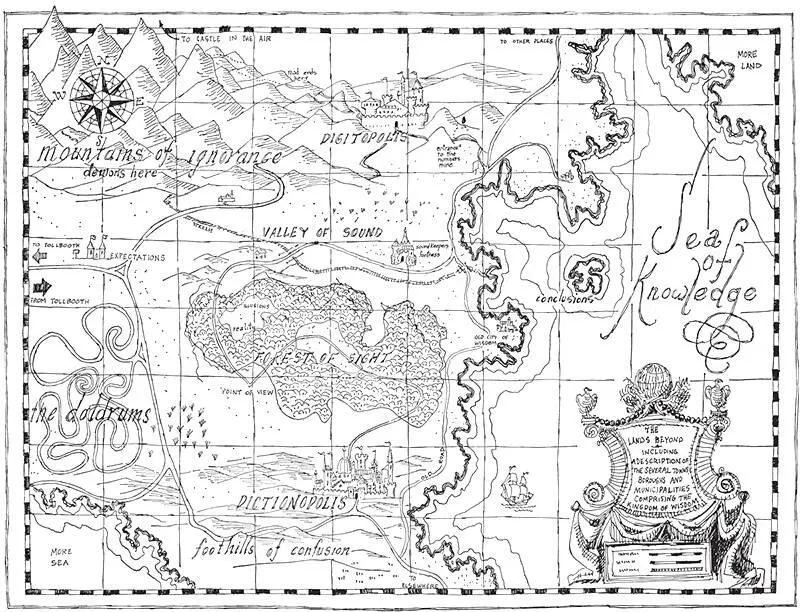

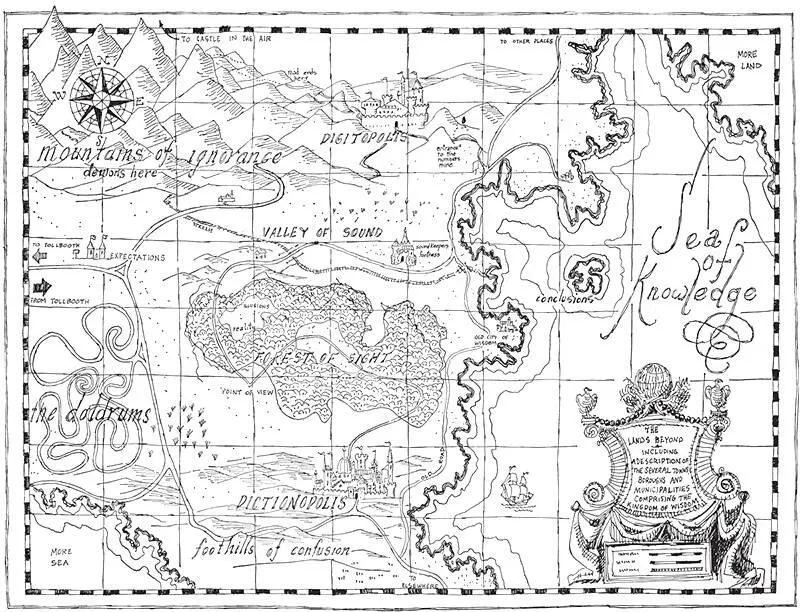

Rereading it now (even Milo would be amazed at the quick whirling away of thirty-five years), I am touched all over again by the confidence, certainty, and radiance of a book that knew it had to exist. It provides the same shock of recognition as it did then—the same excitement and sheer delight in glorious lunatic linguistic acrobatics. It is also prophetic and scarily pertinent to late-nineties urban living. The book treats, in fantastical terms, the dread problems of excessive specialization, lack of communication, conformity, cupidity, and all the alarming ills of our time. Things have gone from bad to worse to ugly. The dumbing down of America is proceeding apace. Juster’s allegorical monsters have become all too real. The Demons of Ignorance, the Gross Exaggeration (whose wicked teeth were made “only to mangle the truth”), and the shabby Threadbare Excuse are inside the walls of the Kingdom of Wisdom, while the Gorgons of Hate and Malice, the Overbearing Know-it-all, and most especially the Triple Demons of Compromise are already established in high office all over the world. The fair princesses, Rhyme and Reason, have obviously been banished yet again. We need Milo! We need him and his endearing buddies, Tock the watchdog and the Humbug, to rescue them once more. We need them to clamber aboard the dear little electric car and wind their way around the Doldrums, the Foothills of Confusion, and the Mountains of Ignorance, up into the Castle in the Air, where Rhyme and Reason are imprisoned, so they can restore them to us. While we wait, let us celebrate the great good fortune that brought The Phantom Tollbooth into our lives thirty-five happy years ago. Mazel tov, Milo, Norton, and Jules!

MAURICE SENDAK

1996

There was once a boy named Milo who didn’t know what to do with himself—not just sometimes, but always.

When he was in school he longed to be out, and when he was out he longed to be in. On the way he thought about coming home, and coming home he thought about going. Wherever he was he wished he were somewhere else, and when he got there he wondered why he’d bothered. Nothing really interested him—least of all the things that should have.

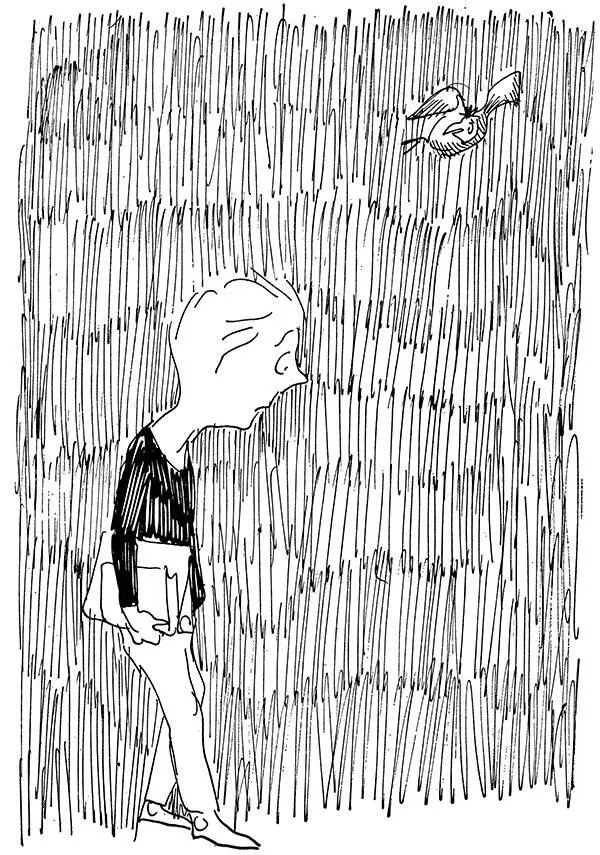

“It seems to me that almost everything is a waste of time,” he remarked one day as he walked dejectedly home from school. “I can’t see the point in learning to solve useless problems, or subtracting turnips from turnips, or knowing where Ethiopia is or how to spell February.” And, since no one bothered to explain otherwise, he regarded the process of seeking knowledge as the greatest waste of time of all.

As he and his unhappy thoughts hurried along (for while he was never anxious to be where he was going, he liked to get there as quickly as possible) it seemed a great wonder that the world, which was so large, could sometimes feel so small and empty.

“And worst of all,” he continued sadly, “there’s nothing for me to do, nowhere I’d care to go, and hardly anything worth seeing.” He punctuated this last thought with such a deep sigh that a house sparrow singing nearby stopped and rushed home to be with his family.

Without stopping or looking up, Milo dashed past the buildings and busy shops that lined the street and in a few minutes reached home—dashed through the lobby—hopped onto the elevator—two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, and off again—opened the apartment door—rushed into his room—flopped dejectedly into a chair, and grumbled softly, “Another long afternoon.”

He looked glumly at all the things he owned. The books that were too much trouble to read, the tools he’d never learned to use, the small electric automobile he hadn’t driven in months—or was it years?—and the hundreds of other games and toys, and bats and balls, and bits and pieces scattered around him. And then, to one side of the room, just next to the phonograph, he noticed something he had certainly never seen before.

Читать дальше