“A very pretty speech—s-p-e-e-c-h,” sneered the bee. “Now why don’t you go away? I was just advising the lad of the importance of proper spelling.”

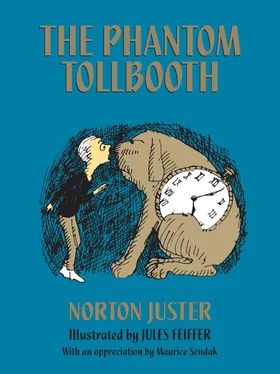

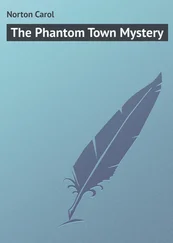

“BAH!” said the bug, putting an arm around Milo. “As soon as you learn to spell one word, they ask you to spell another. You can never catch up—so why bother? Take my advice, my boy, and forget about it. As my great-great-great-grandfather George Washington Humbug used to say——”

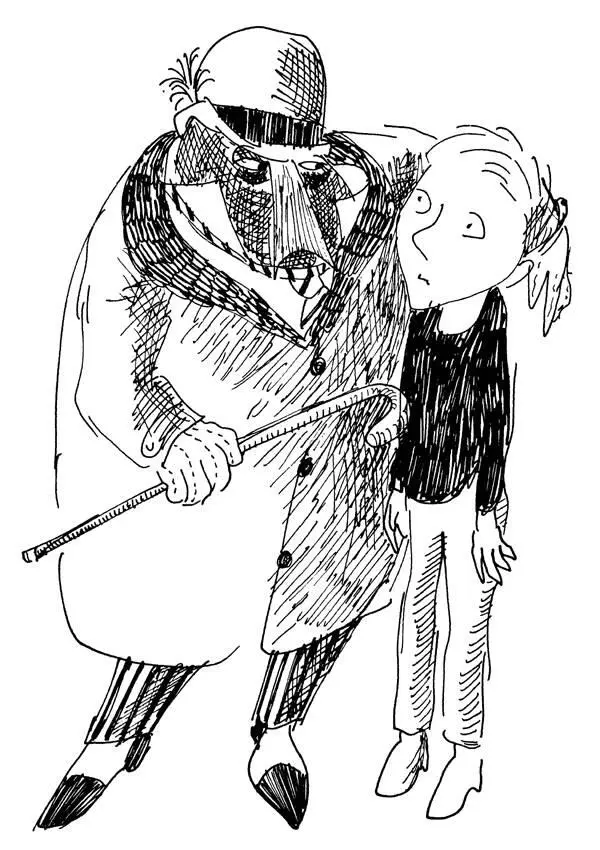

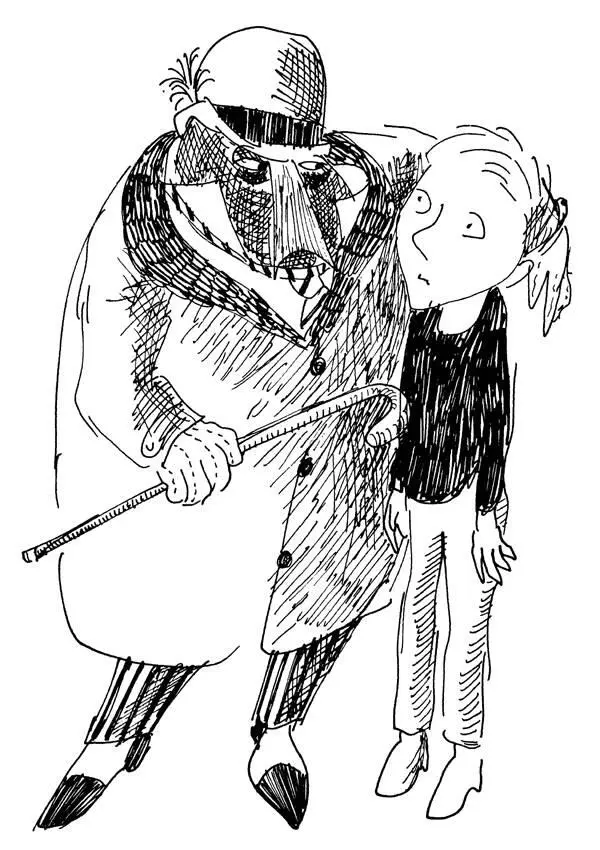

“You, sir,” shouted the bee very excitedly, “are an impostor—i-m-p-o-s-t-o-r—who can’t even spell his own name.”

“A slavish concern for the composition of words is the sign of a bankrupt intellect,” roared the Humbug, waving his cane furiously.

Milo didn’t have any idea what this meant, but it seemed to infuriate the Spelling Bee, who flew down and knocked off the Humbug’s hat with his wing.

“Be careful,” shouted Milo as the bug swung his cane again, catching the bee on the foot and knocking over the box of W’s.

“My foot!” shouted the bee.

“My hat!” shouted the bug—and the fight was on.

The Spelling Bee buzzed dangerously in and out of range of the Humbug’s wildly swinging cane as they menaced and threatened each other, and the crowd stepped back out of danger.

“There must be some other way to——” began Milo. And then he yelled, “WATCH OUT,” but it was too late.

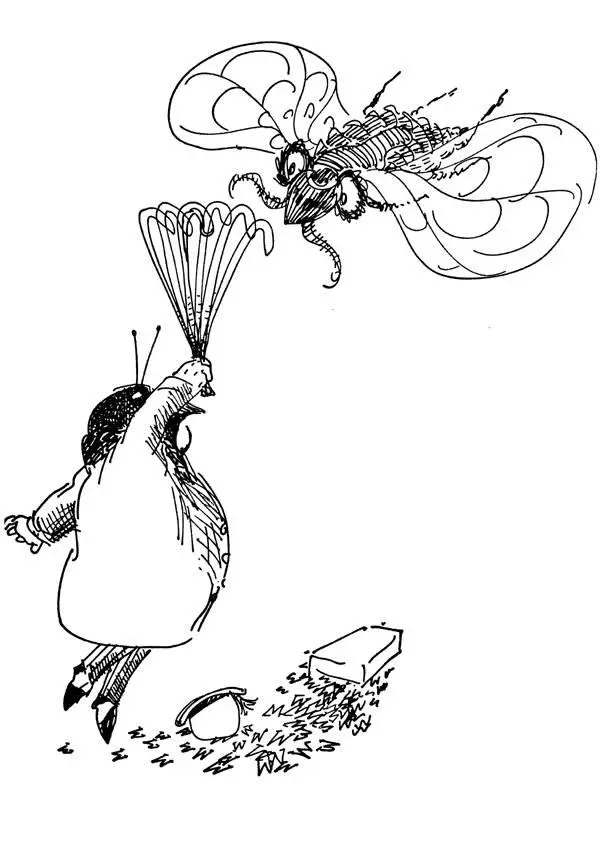

There was a tremendous crash as the Humbug in his great fury tripped into one of the stalls, knocking it into another, then another, then another, then another, until every stall in the market place had been upset and the words lay scrambled in great confusion all over the square.

The bee, who had tangled himself in some bunting, toppled to the ground, knocking Milo over on top of him, and lay there shouting, “Help! Help! There’s a little boy on me.” The bug sprawled untidily on a mound of squashed letters and Tock, his alarm ringing persistently, was buried under a pile of words.

“Done what you’ve looked,” angrily shouted one of the salesmen. He meant to say “Look what you’ve done,” but the words had gotten so hopelessly mixed up that no one could make any sense at all.

“Do going to we what are!” complained another, as everyone set about straightening things up as well as they could.

For several minutes no one spoke an understandable sentence, which added greatly to the confusion. As soon as possible, however, the stalls were righted and the words swept into one large pile for sorting.

The Spelling Bee, who was quite upset by the whole affair, had flown off in a huff, and just as Milo got to his feet the entire police force of Dictionopolis appeared—loudly blowing his whistle.

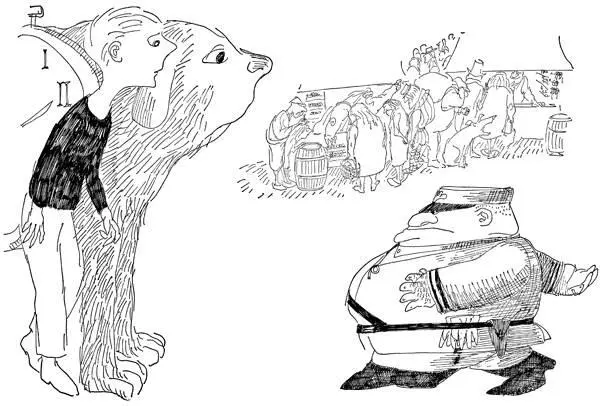

“Now we’ll get to the bottom of this,” he heard someone say. “Here comes Officer Shrift.”

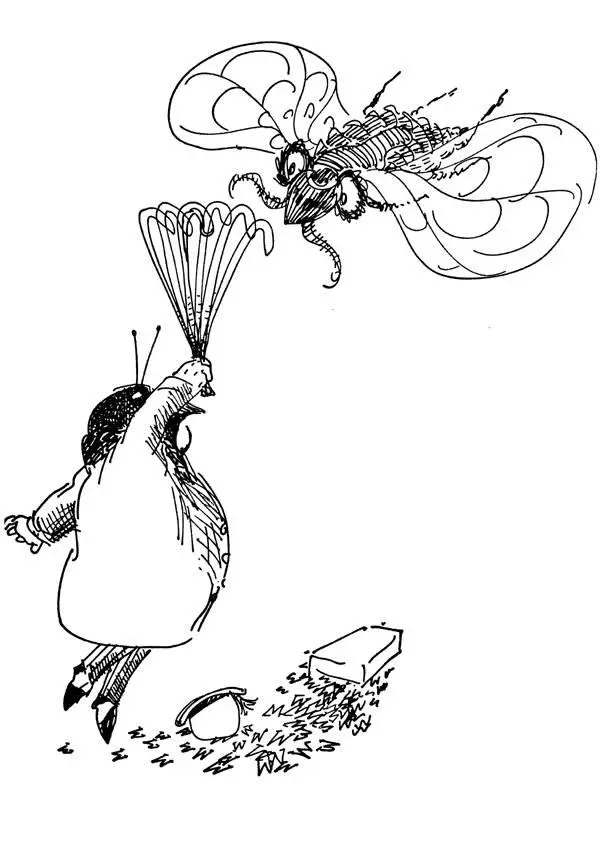

Striding across the square was the shortest policeman Milo had ever seen. He was scarcely two feet tall and almost twice as wide, and he wore a blue uniform with white belt and gloves, a peaked cap, and a very fierce expression. He continued blowing the whistle until his face was beet red, stopping only long enough to shout, “You’re guilty, you’re guilty,” at everyone he passed. “I’ve never seen anyone so guilty,” he said as he reached Milo. Then, turning towards Tock, who was still ringing loudly, he said, “Turn off that dog; it’s disrespectful to sound your alarm in the presence of a policeman.”

He made a careful note of that in his black book and strode up and down, his hands clasped behind his back, surveying the wreckage in the market place.

“Very pretty, very pretty.” He scowled. “Who’s responsible for all this? Speak up or I’ll arrest the lot of you.”

There was a long silence. Since hardly anybody had actually seen what had happened, no one spoke.

“You,” said the policeman, pointing an accusing finger at the Humbug, who was brushing himself off and straightening his hat, “you look suspicious to me.”

The startled Humbug dropped his cane and nervously replied, “Let me assure you, sir, on my honor as a gentleman, that I was merely an innocent bystander, minding my own business, enjoying the stimulating sights and sounds of the world of commerce, when this young lad——”

“AHA!” interrupted Officer Shrift, making another note in his little book. “Just as I thought: boys are the cause of everything.”

“Pardon me,” insisted the Humbug, “but I in no way meant to imply that——”

“SILENCE!” thundered the policeman, pulling himself up to full height and glaring menacingly at the terrified bug. “And now,” he continued, speaking to Milo, “where were you on the night of July 27?”

“What does that have to do with it?” asked Milo.

“It’s my birthday, that’s what,” said the policeman as he entered “Forgot my birthday” in his little book. “Boys always forget other people’s birthdays.

“You have committed the following crimes,” he continued: “having a dog with an unauthorized alarm, sowing confusion, upsetting the applecart, wreaking havoc, and mincing words.”

“Now see here,” growled Tock angrily.

“And illegal barking,” he added, frowning at the watchdog. “It’s against the law to bark without using the barking meter. Are you ready to be sentenced?”

“Only a judge can sentence you,” said Milo, who remembered reading that in one of his schoolbooks.

“Good point,” replied the policeman, taking off his cap and putting on a long black robe. “I am also the judge. Now would you like a long or a short sentence?”

“A short one, if you please,” said Milo.

“Good,” said the judge, rapping his gavel three times. “I always have trouble remembering the long ones. How about ‘I am’? That’s the shortest sentence I know.”

Everyone agreed that it was a very fair sentence, and the judge continued: “There will also be a small additional penalty of six million years in prison. Case closed,” he pronounced, rapping his gavel again. “Come with me. I’ll take you to the dungeon.”

“Only a jailer can put you in prison,” offered Milo, quoting the same book.

“Good point,” said the judge, removing his robe and taking out a large bunch of keys. “I am also the jailer.” And with that he led them away.

“Keep your chin up,” shouted the Humbug. “Maybe they’ll take a million years off for good behavior.”

The heavy prison door swung back slowly and Milo and Tock followed Officer Shrift down a long dark corridor lit by only an occasional flickering candle.

“Watch the steps,” advised the policeman as they started down a steep circular staircase.

The air was dank and musty—like the smell of wet blankets—and the massive stone walls were slimy to the touch. Down and down they went until they arrived at another door even heavier and stronger-looking than the first. A cobweb brushed across Milo’s face and he shuddered.

“You’ll find it quite pleasant here,” chuckled the policeman as he slid the bolt back and pushed the door open with a screech and a squeak. “Not much company, but you can always chat with the witch.”

“The witch?” trembled Milo.

“Yes, she’s been here for a long time,” he said, starting along another corridor.

Читать дальше