In fact, bourach ( BOO-rackh , where the ckh is pronounced at the back of the throat, as in loch ) has several meanings, all of them coming from the original sense of a pile or a heap. The Lanarkshire poet John Black, in his collection Melodies and Memories , wrote in 1909 of tea parties with ‘Bourachs big o’ cake and bun, to grace the feasts an’ spice the fun.’ It also came to mean a cluster or a small group of people, birds or animals, and at the same time a small hut, particularly one used by children to play in – presumably because such a rough hut might well look like a pile of stones.

But it’s in the sense of a mess or a state of confusion that it’s mostly used today, and the comparison with guddle helps to define both words. Guddle was originally a verb, which meant to grope around uncertainly under water and, more particularly, to try to catch a fish with your bare hands. From that sense of blind uncertainty, it gained the meaning that it has today. It has an attractive sound, but we have any number of words already that mean much the same thing – think of muddle, mess or jumble.

So a bourach is like a guddle , only more so.

Either one is a splendidly evocative word for a whole variety of confusions, from the organizational shambles of the Scottish election to the normal state of a teenager’s bedroom, to the chaos that follows the start of roadworks on a busy street. The difference is that a guddle is a bit of a tangle that can be sorted with some patience and application, whereas a bourach is the sort of rats’ nest of chaos that makes you want to throw your hands in the air and give up.

So, while a guddle is often something that has simply happened – nobody’s fault, just an example of how things can go wrong – a bourach is often the result of someone’s good intentions going awry. You can make a bourach of a place or of a job, but either way it’s going to be the sort of experience that you won’t forget in a hurry. Suppose, for instance, that you are baking a cake. The kitchen can often get in a bit of a guddle , particularly if you don’t put things away and wash up as you go. You’ll have a lot of tidying up and clearing to do once the cake’s in the oven, but with a bit of work everything will be fine by the time it’s cooked.

But now add in a four-year-old child who’s desperate to help. Not only will they keep getting extra plates and cake tins out of the cupboard in case you need them, they’ll also want to sift the flour for you and end up getting it all over the floor, the curtains and probably themselves. They may decide, while your back is turned, that what the cake really needs is a sprinkling of chocolate chips, but in reaching to take them down from the shelf, they’ll spill most of them and eat the rest. Half a pound of sugar will vanish down the back of a cupboard, and along the way a whole bottle of milk will be spilt, two eggs will be dropped on the floor and three of your favourite dishes will end up in pieces. Between you, you will have made a complete bourach of the kitchen.

And then, when you forget to take the cake out of the oven, you’ll have made a bourach of that as well.

An off-the-wall idea that comes from a drinking session

Good ideas don’t just come from nowhere. We all need something to spark the imagination, to get our thoughts running, and sometimes that something is a couple of drinks. Alcohol can set off all sorts of ideas, but most of them aren’t good at all. Making decisions after a late-night session is seldom a sensible plan. Most of the inspiration that comes out of the neck of a bottle would have been better left deeply buried in your subconscious.

The Germans have a word for the sort of idea that results – a schnapsidee ( SHNAPS-i-day ) is, literally, a ‘booze-idea’, and it’s used to describe a suggestion that is seen as completely impractical. Schnaps is the German for spirits or strong liquor, but the word is used even when there’s no implication that the person putting forward the idea has been drinking. A young child could have a schnapsidee , or a teetotal church minister.

The point about a schnapsidee that English finds it impossible to get across in phrases such as ‘hare-brained plan’ or even ‘midsummer madness’ – which are a couple of translations that are sometimes suggested – is that it’s not just a bad idea, it’s an idea so ridiculous that you cannot have been thinking straight when you came up with it. It’s thoughtlessly, self-indulgently stupid.

But that makes it sound like a very solemn, judgemental term, which it’s not. Schnapsidee is generally used about less consequential ideas rather than serious issues. You might say that swimming in a river on Christmas Day is a schnapsidee , but a German wouldn’t have used the word – even if he’d dared to – to tell Hitler what he thought of his idea of marching to Moscow.

However, it has just the degree of surprised incredulity that we sometimes want to express about grandiose political programmes: ‘I just can’t believe anyone could ever have thought that was a good idea!’ It could apply on all sides of political divides. Calling a strike? Schnapsidee . Sending the police or the army to break a strike? Schnapsidee . Leave the European Union (or join the European Union)? Schnapsidee .

At the risk of getting into the dangerous area of national stereotypes, are the Germans maybe given to working things out in detail, planning, dotting every i and crossing every t? If so, perhaps that’s why they’ve won the football World Cup four times, but it might also explain why they have such a downer on off-the-wall ideas that come out of a bottle of booze.

If we’re going to steal someone else’s word and make it our own, we should take the chance to be really radical. While most ideas that come with the tang of alcohol on them would be better quietly forgotten, there are some that fly – some that come from a place deep inside us, where we have no inhibitions, where we have ideas that fizz and change the world. If a drink or two can unlock the door to that place, then we shouldn’t be so keen to write off the schnapsidee .

Imagine a Spanish merchant in the mid-fifteenth century sharing a glass of wine on the waterfront at Palos de la Frontera with a sea captain in his forties – not a young man in those days. ‘OK, Columbus, so you’re planning a trip to the Indies … but you want to sail which way?’ And off he wanders, shaking his head at the madness of the fool he’s just been talking to, the schnapsidee of it all – never guessing that a new world lies somewhere over the horizon and that the ‘fool’ will soon be walking on its beaches.

Why shouldn’t we use schnapsidee to mean an idea that seems to be wild and crazy, and leave open the possibility that it just might be a flash of the purest brilliance?

Here’s to the schnapsidee !

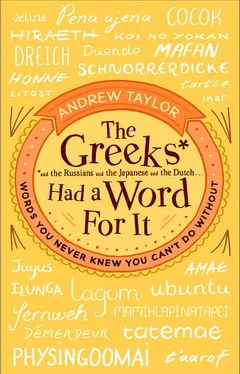

I’ve gone to many native speakers of different languages for help with writing this book, and also to scholars who have spent years gaining a deep understanding of a language that fascinates them. What they’ve all had in common is their enthusiasm – people want to share things that they find special about a language that they love.

There are too many to list them all, but I owe particular thanks to Bariya Ataya, Tamsin Craig, Elsa Davies, Eva Dingwall, Irakli Gabriadze, Orit Gadiesh, Quinten Gueurs, Ricky Lacey, Professor Vali Lalioti, Nino Madghachian, Professor Mark Riley, Wendy Robbins, Pat Roberts and Georgi Vardeli.

Читать дальше